© Wordsworth Editions

Another Halloween-inspired reposting about books of Victorian and Edwardian ghost stories…

I’ve just read two more collections of ghost stories published in the excellent Wordsworth Editions’ Tales of Mystery and Imagination series. Other books in this series have featured work by still-celebrated writers like E.F. Benson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, M.R. James and Edith Wharton; but also by writers like Gertrude Atherton, Amayas Northcote, J.H. Riddell and May Sinclair, who were prolific and / or acclaimed in their day but whose names slipped into obscurity following their deaths. Getting republished by Wordsworth Editions might, of course, help to rescue their names from obscurity.

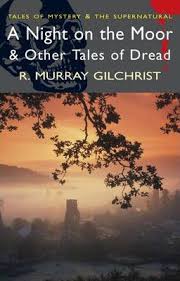

The two latest Wordsworth collections I’ve read were both published in 2006. They are A Night on the Moor and Other Tales of Dread by R. Murray Gilchrist and Aylmer Vance: Ghost-Seer by Alice and Claude Askew.

Firstly, I’ll talk about the collection I enjoyed less. R. Murray Gilchrist was born in Sheffield but lived for much of his life in Holmesfield, 800 feet up in Derbyshire’s Peak District. By the time of his death in 1917 at the age of 50, he was responsible for 22 novels and about 100 short stories. However, A Night on the Moor and Other Tales of Dread is something of a misnomer because most of the stories featured don’t particularly evoke feelings of ‘dread’. Rather, they are tales of darkly gothic romance, where the atmosphere – and, alas, the prose – is often stiflingly thick.

These are stories where every building is an imposing structure with ‘stacks of twisted chimneys’ and ‘great square windows’ and is ‘a vision of gables’ that’s ‘so covered in ivy that from a distance it seems like a cluster of rare trees with ruddy trunks and branches’; where every garden is adorned with statues of satyrs, nymphs, dryads, dragons and the goddess Diana; and where the air is always suffused with the sickly-sweet smells of flowers, such as roses, lilies, honeysuckle, ‘withering snowdrops’ and ‘scarlet poppies, with hearts like fingers’ that effuse ‘a close and sleepy perfume’. The villain of the story The Manuscript of Francis Shackerley even gives off ‘a rich smell of violets’ and it’s said that ‘his skin by some artificial means had been impregnated lastingly with their odour.’

Unfortunately, Gilchrist’s writing is frequently hamstrung by melodrama (“O the midsummer noontide; the trembling air; the golden dusk that clung around the fir trunks!”) and is occasionally, clunkingly awful (“My thoughts had withered, my words had grown unpregnant”). There’s an attempt to emulate the morbid, decadent intensity found in such tales by Edgar Allan Poe as Berenice (1835), Ligeia (1938), The Oval Portrait (1842) and Eleonora (1850), but while characters indulge in much internal and external pontificating and running hither and thither to no great effect, the impression you get is one of bluster rather than of anything genuinely, dissolutely macabre. Some of the stories I found a real chore to get through.

Still, there are a few items where Gilchrist dials it down a bit and manages to strike a properly creepy note. The Lover’s Ordeal is a tale of a dare that unexpectedly ends up featuring a vampire. The Grotto at Ravensdale sees a newly married couple encounter tragedy at the titular, and haunted, cavern. The Priest’s Pavan is about a harpsichordist forced to play some demonic music at a wedding party. And A Night on the Moor itself is an atmospheric piece where the main character experiences a time-slip.

Also, two additional stories, The Panicle and The Witch in the Peak, are tagged on in an appendix at the end. Presumably this is because they eschew the aristocratic characters, lavishly gothic settings and rather po-faced tone of the other stories and instead have straightforward and refreshingly humorous narratives where working-class people experience supernatural goings-on in the Peak District. The 19-century Derbyshire dialect is rather hard to decipher, but I enjoyed these two stories more than anything else in the collection and would have liked more with their flavour.

© Wordsworth Editions

Aylmer Vance: Ghost-Seer is more modest in its ambitions and I have to say I found it the more enjoyable read because of that. It has eight stories, all connected by the recurring character of Aylmer Vance – ‘a curious-looking man, tall and lean in build, with a pale but distinctly interesting face’ – who as the title indicates is sensitive to paranormal activity and acts as a supernatural detective, trying to explain and put an end to hauntings suffered by other people. The narrator, however, is an acquaintance of Vance’s called Dexter. Vance tells the first three stories to Dexter, then Dexter becomes an unwilling participant in the fourth one, and then for the remaining four stories joins forces with Vance and serves as a Dr Watson to his Sherlock Holmes.

There’s nothing spectacular here, but there are some imaginative ideas – the fire-raising ghost of a frustrated poet in The Fire Unquenchable, for example, or the malevolent spirit of a pianist using his music to haunt the woman he lusted after when alive in The Indissoluble Bond. Meanwhile, The Stranger, about a young woman attracted to a mysterious figure she encounters in a local wood, is a nicely pagan affair with a hint of Arthur Machen; and the final story, The Fear, is impressively oppressive and ‘does what it says on the tin’.

Unfortunately, I didn’t enjoy Aylmer Vance as much as I might have done. This was because a year earlier I’d read a Wordsworth Editions collection called Carnacki, the Ghost-Finder, written by William Hope Hodgson, which was a set of tales about, yes, another supernatural detective called Thomas Carnacki. The Carnacki stories were good enough to have influenced later writers like H.P. Lovecraft and Dennis Wheatley and the Vance stories can’t help but seem a little pedestrian in comparison.

Aylmer Vance also suffers from a problem that’s inevitable when you have a series of supernatural stories that are mostly self-contained and have different elements (ghosts, poltergeists, vampires, etc.) but also have the thread of a recurring character. If paranormal activity does happen, it must happen incredibly rarely. Otherwise scientists would have observed and recorded it and acknowledged its existence by now. So how does someone like Vance manage to defy all laws of probability and have eight full-blooded encounters with the supernatural in its different forms? William Hope Hodgson at least seemed aware of this credibility problem, for he interspersed his genuinely supernatural Carnacki stories with ones where the hauntings turn out to be hoaxes.

Vance writers Alice and Claude Askew, incidentally, were a husband-and-wife team who supposedly penned over 90 novels during a 14-year period in the early 20th century. During World War One, they found themselves in Serbia and later in Greece, working at a British field hospital and then for the Serbian Red Cross and also writing war despatches for publications like the Daily Express. Like R. Murray Gilchrist, they died in 1917 but in a particularly tragic manner. Both were killed while they were travelling from Italy to Corfu, when their boat was torpedoed by a German submarine. Claude’s body was never found. However, Alice’s body was recovered and she’s buried on the Croatian island of Korčula.