From wikipedia.org / © The Washington Post

“What would you say to Epstein survivors…?”

“You are so bad. You are the worst reporter. No wonder CNN has no ratings. She’s a young woman. I don’t think I’ve ever seen you smile. They should be ashamed of you.”

On February 4th, CNN reporter Kaitlan Collins was cut off in the middle of a question about the victims of Jeffrey Epstein, notorious paedophile, human trafficker and friend to the rich and famous, at a White House press conference. Cutting her off was President Donald Trump, coincidentally someone who receives, according to the New York Times, 38,000 mentions in the Epstein files so far released by the US Department of Justice. Evidently, in Trump’s mind, you need to smile when you ask questions about victims of paedophilia and human trafficking.

I find his objection ironic considering that for the last 21 years Trump’s been married to Melania Trump, a woman on whose visage – gimlet-eyed and as smooth, hard and unyielding as an iron bedpan – anything resembling a smile rarely flickers. Obviously, though, if you were expected to share a marital bed with Trump, your face wouldn’t be projecting sunbeams and rainbows either.

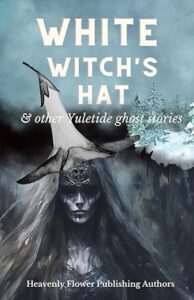

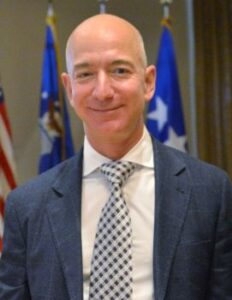

Lately, Melania Trump has been in the news because of the release of a new documentary movie about her. Entitled Melania, it focuses on her during the run-up to her husband’s second inauguration as president. Jeff Bezos’s Amazon paid 40 million dollars for the rights to the documentary – 28 million of that reportedly going straight into Ms. Trump’s pocket – and another 35 million to advertise it.

Reviews of Melania have not been, shall we say, overly enthusiastic. The last time I checked the review aggregate site Rotten Tomatoes, its ‘Tomato-meter’ had it at seven percent. William Thomas at Empire magazine advised, “Do try not to choke on your popcorn.” Sean Burns at North Shore Movies observed, “At least Leni Riefenstahl could frame a shot.” Mark Kermode at Kermode and Mayo’s Take – The Brand New Podcast described it as “the most depressing experience I have ever had in the cinema.” He added, “I mean, I’ve seen A Serbian Film (2010), I’ve seen Cannibal Holocaust (1980), I have never felt this depressed… I thought it was absolutely repugnant.”

By the way, the director of Melania is Brett Ratner, who in 2017 was accused of sexual assault and harassment by six women, accusations he’s denied. In photos recently released from the Epstein files, he appears sitting on a sofa beside the late, loathsome paedophile, both of them cuddling young women. The women’s faces are blocked to protect their identities, so you can’t tell how young they are.

I should also say that Melania made seven million dollars on its opening weekend, a decent haul for a documentary. Obviously, it appeals to a certain audience in the USA, i.e., cultish MAGA dingbats so worshipful of her husband they’d spend a fortune on eBay to acquire pieces of his used toilet paper, which they’d then frame and hang prominently in their living rooms. However, it still looks like it’ll be a long time before Amazon recoups anything like the 75 million dollars it invested in the movie.

From wikipedia.org / © White House

In totally unconnected developments during Trump’s first year as 47th president, the Orange One signed an executive order relaxing environmental rules about space launches (benefiting Bezos’s private space venture Blue Origin); signed an order preventing US states from enforcing their own AI regulations (benefiting Bezos’s AI start-up Project Prometheus); and generally created a oligarch-friendly climate that’s allowed Bezos and fellow magnificoes Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg to increase their collective wealth by approximately 250 billion dollars.

But I don’t know why Bezos would take a financial hit by getting involved in Melania, a vanity project that nobody apart from those hardcore MAGA nutters would pay money to see. I really don’t know.

In other, totally unconnected news last week, the Washington Post, a once-respected newspaper whose motto is ‘Democracy dies in darkness’, and which broke the story about the Watergate scandal that brought down Richard Nixon’s presidency in 1974, has announced a ‘strategic reset’. This reset involves showing a third of its current workforce the door. It’s also “ending the current iteration of its popular sports desk… restructuring its local coverage, reducing its international reporting operation, cutting its books desk and suspending its flagship daily news podcast Post Reports.” The loss of the Washington Post’s books desk means it’ll no longer publish its literary review supplement Book World.

The Washington Post has been on a downward spiral this past year, a spiral of its – or its proprietor’s – own making. Previously, and unsurprisingly, it’d not been enamoured with Trump. As 2024’s presidential race neared election day, however, and with Trump looking likely to regain the White House and launch his glorious new thousand-year Reich, the Washington Post’s editorial board was ordered not to publish an editorial endorsing Kamala Harris, Trump’s rival for the presidency. As a result, more than 200,000 disgusted readers – eight percent of its 2.5 million-strong readership – cancelled their digital subscriptions to the newspaper.

After the announcement of the Washington Post‘s downsizing, its legendary Watergate reporter Bob Woodward lamented, “I am crushed that so many of my beloved colleagues have lost their jobs and our readers have been given less news and sound analysis. They deserve more.” Meanwhile, Trump’s Communications Director Steve Cheung crowed on Twitter, “Just a reminder that printing fake news is not a profitable business model.”

Earlier, the Washington Post’s proprietor had defended his decision to have the newspaper sit on the fence before the 2024 election, which’d started the rot. He wrote: “Presidential endorsements do nothing to tip the scales of an election… What presidential endorsements actually do is create a perception of bias. A perception of non-independence. Ending them is a principled decision, and it’s the right one.” Aye, right. That’s the principled thing to do. When there’s a choice between a candidate who’s a convicted criminal and convicted sexual abuser and a candidate who isn’t, you say nothing. Heaven forbid anyone perceives you as being biased and non-independent.

From wikipedia.org / © Van Ha, US Space Force

And who’s the proprietor of the Washington Post? Oh look, it’s Jeff Bezos. Funny that he should take a hit by alienating his newspaper’s natural readership and sending it down the toilet, just as he took a hit by shelling out 75 million dollars for a dud like the Melania movie. It’s almost like he has an ulterior motive. Almost like he’s trying to… curry favour with someone.

But seriously. A while ago, I posted about “an unholy alliance of authoritarians, kleptocrats, fascists, media tycoons, tech bros and oil barons”, working hard “at stripping freedoms from those of us living in societies that, until now, have retained some freedoms; at transferring another huge chunk of wealth from our dwindling coffers to their swelling coffers; and at burning and poisoning the planet we live on in their quest for profits whilst aggressively pushing the line that any science questioning this policy is a ‘hoax’.” You see that here. Bezos grovelling to Trump by financing his missus’s dreadful movie and nuking the Washington Post. As a reward, Trump throwing him a few legislative and financial scraps from the White House table so he can carry on making pots of money for himself.

And with Bezos and his ilk embracing automation and Artificial Intelligence to maximise profits by eliminating human employees, and salaries, the future looks grim. Journalists will soon go the way of lamplighters, elevator operators, switchboard operators and video store clerks. News copy will be written by AI technology, controlled by billionaires, who’ll make sure that copy panders to their interests and those of their political allies. And if there’s bad news they can’t avoid reporting, it’ll be blamed on those people not plugged into their extreme-right-wing, white-Christian-nationalist gestalt: blacks, Latinos, Muslims, Jews, atheists, gays, trans-people, liberals, socialists, trade unionists.

Education will be similar. Teachers will disappear too and kids will be taught by AI, with the likes of Elon Musk deciding what’s in the curriculum. Indeed, Musk has done a deal with El Salvador’s government to “bring his artificial intelligence company’s chatbot, Grok, to more than 1 million students across the country… to ‘deploy’ the chatbot to more than 5,000 public schools in an ‘AI-powered education program’.” Yes, that’s Grok, the lovable chatbot that praises Hitler and puts tweens in tiny bikinis for the gratification of paedophiles, coming to a school near you to teach your kids.

The stinking rich and stinking powerful won’t only hoard wealth – they’ll hoard information too, whilst making sure only small, approved increments of it leak down to the masses they regard as their serfs and inferiors. Especially manipulated will be scientific information about the climate catastrophe posing an increasing threat to our civilisation’s survival on this planet. So that their environmentally-ruinous cash-generating projects, like power-guzzling and water-guzzling AI data centres, escape censure, they’ll suppress this information or bury it under an avalanche of counter-arguing pseudoscientific gibberish, or not collect it in the first place.

But let’s end positively. While it’s sickening to watch America’s business magnates, corporations, media organisations, law firms and universities bend over supinely and lick Trump’s gruesome arse, the way ordinary Americans have reacted to his policies gives glimmers of hope.

© MS NOW

I’m thinking especially of Minneapolis. Since December, the city has been overrun and brutalised by up to 3000 of Trump’s masked, violent, badly-trained thugs from Immigration and Customs (ICE) and Customs and Border Patrol. Ostensibly, they came to crack down on fraud allegedly committed by Minneapolis’s Somali-American community. In reality, as Wikipedia reports, they’ve assaulted, harassed and detained people “on the basis of their alleged or suspected immigration status”, including “restaurant, airport and hotel workers, Target employees, children and families, Native Americans, students and commuters”, many of whom “have been US citizens, legal residents with work authorisation, or asylum seekers.”

This has disastrously impacted on the city’s businesses, schools and whole social fabric. ICE was accused of violating at least 96 court orders during four weeks in January alone; and they’ve executed two citizens during peaceful protests, Renee Good on January 7th and Alex Pretti on January 24th.

Obviously, the operation was designed to intimidate Minneapolis – whose state governor is Tim Walz, Kamala’s running mate against Trump in 2024 – and intimidate liberal-leaning cities generally. But local people are having none of it. They’ve protested peacefully, organized strikes, alerted neigbours about approaching ICE patrols, monitored and filmed their activities, and provided support for people at risk from those activities by helping them get to their schools and places of worship unmolested, running errands for them and raising money for them. They’ve stood by their fellow citizens in a display of decent, old-fashioned community values – values Trump would despise if his reptile brain could ever understand them in the first place.

One thing that particularly impressed and moved me was a viral clip showing a white-bearded old man protesting against ICE on a snowbound and teargas-fogged Minneapolis street on January 24th. When a reporter and camera crew approached him, he raged, “I’m just angry. I’m 70 years old and I’m f**king angry.” Then, wearing neither mask nor goggles, he strode off through a billowing wall of teargas.

That furious but defiant old-timer, it transpired, was Greg Ketter, founder and proprietor of the Minneapolis independent bookstore DreamHaven Books and Comics. The renowned sci-fi and fantasy writer Harlan Ellison once described DreamHaven as “a book-seeker’s cave of miracles”.

I find it inspiring to see a man who’s devoted a lifetime to books taking a stand against Trump, someone who brags about not reading as if it’s a badge of honour. And by extension, against Trump’s billionaire toadies, currently trying to create an AI dystopia wherein novels and other human art-forms are replaced by soulless, AI-generated slop. And against Trump’s toady at Amazon, Jeff Bezos, who’s just axed the Washington Post’s Book World, one of the very few literary supplements the American newspaper industry had left.

From wikipedia.org / © DreamHaven Books & Comics