From wikipedia.org / Scottish National Portrait Gallery

It’s Burns Night this evening. In other words, it’s been 267 years exactly since Agnes Burnes (né Broun) gave birth to little Robert Burns, who would grow up to be Scotland’s greatest poet. I currently reside in Singapore and am not connected with the city-state’s St Andrew’s Society (whom I believe organise an annual Burns Supper in this part of the world), so I won’t be celebrating the bard’s birthday in the traditional fashion, i.e., quaffing whisky, listening to poetry recitals, quaffing more whisky, stuffing myself with haggis, neeps and tatties, and quaffing yet more whisky. However, I’ll make sure tonight I drink a couple of bottles of Tiger Beer to the great man’s memory in my local bak-kut-teh eatery – and will post this latest instalment in my series about my favourite words in the Scots language, the medium in which Burns wrote his poetry.

Here, I’ll cover those Scots words beginning with the final four letters of the alphabet. Actually, beginning with just ‘W’ and ‘Y’, since I don’t know of any ones beginning with ‘X’ and ‘Z’, unless you count Zetland, an old name for the Shetland Islands.

Wally (adj) – porcelain. I believe I mentioned this before when I covered the term peely-wally, meaning pale and sickly-looking to the point where the person so described is the colour of porcelain. A wally dug is a porcelain ornament in the form of a dog, while wallies is a Scots term for dentures – porcelain was first used to make false teeth in the late 18th century and was still a component in their manufacture two centuries later. Finally, a fancy alleyway lined with porcelain tiles is referred to as a wallie close.

Wean (noun) – a young child. Wean is a blend of the words wee and ane (one). For example, Glaswegian poet Liz Lochhead’s 1985 Scots-language adaptation of Molière’s Tartuffe (1664) contains the couplet, “Can you bring the wean up well / When you’re scarce mair than a lassie yoursel’?”

Wee (adj) – small. One of the commonest and most famous Scots words, wee isn’t just used across Scotland but in the north of England and Ireland too. It’s frequently heard in my birthplace Northern Ireland, which contains its own variant of Scots, Ulster-Scots. Indeed, so fond of the word are the inhabitants of Northern Ireland that in the TV show Derry Girls (2018-22), James – ‘The wee English fella’ – remarks on it. “People here,” he cries exasperatedly, “use the word wee to describe things that aren’t even actually that small!”

From derry.fandom.com / © Hat Trick Productions / Channel 4

Back in Scotland, Scots terms that incorporate wee include Wee Free, referring to a member of the Free Church of Scotland, an uncompromising, purist and, well, wee splinter-church from mainstream Presbyterianism; the Wee Rangers, a nickname for Berwick Rangers, a considerably less well-known and wee-er football team than Glasgow Rangers – how everyone in Scotland who wasn’t a Glasgow Rangers supporter laughed when Berwick Rangers beat Glasgow Rangers 1-0 in the first round of the Scottish Cup in 1967; and wee dram , a ‘small’ whisky, though in my experience, anyone who’s offered me a wee dram has served me something not that wee. Come to think of it, I’ve heard wee drams also referred to as wee refreshments, wee libations and wee sensations. Meanwhile, the exclamation “What in the name o’ the Wee Man?” can be translated as “What in the name of the devil?” And I’ve heard a few Scottish teachers in my time refer to their juvenile charges, uncharitably, as wee shites.

Weegie / Weedgie (noun) – an affectionate, and sometimes not so affectionate, term for an inhabitant of Glasgow. I remember lending my copy of Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting (1993) to a Canadian friend during the late 1990s. When she returned it, she said, “I really enjoyed it, but tell me one thing… What’s a Weegie?” Maybe she was puzzled by the musings of the book’s hero / anti-hero, and staunch Edinburgh-er, Mark Renton, who at one point muses: ““Weegies huv this built-in belief that they’re hard done by, but they’re no. It’s just self-pity. Ah mean, Edinburgh’s jist as fuckin bad in places, but ye don’t hear us greetin aboot it aw the f**kin time.”

And I believe another Edinburgh – or Edinburgh-based – author, Iain Rankin, has written at least one crime novel wherein Inspector Rebus is sent to investigate a case 50 miles along the road from the Scottish capital in… Weegie-land.

Whaup (noun) – a curlew.

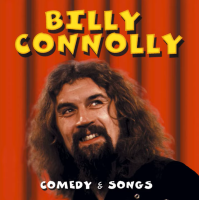

Wheech (verb) – to move very quickly or remove something from somewhere very quickly. The word features in the Billy Connolly stand-up routine about the mechanism that purportedly exists in airplane lavatories, the jobby–wheecher: a sort of “ladle on a string and it’s tucked under the toilet seat, and as soon as you close the lid… WHEECH! Away it goes.”

© Castle Music UK

Whitterick (noun) – a weasel or stoat. This word seems to exist in different forms. In my well-thumbed copy of the Colllin Pocket Scots Dictionary, it’s whitterick. But in Sleekit Mr Tod, James Robertson’s 2008 Scots translation of Roald Dahl’s children’s book Fantastic Mr. Fox (1970), Mr. and Mrs. Weasel are rechristened Mr. and Mrs. Whiteret.

Widdershins / withershins (adverb) – anti-clockwise or in the opposite direction from the sun’s movement across the sky. This gives widdershins and the motion it denotes the connotation of being against the order of things, of being unnatural, of being unlucky and sinister. As a result, it turns up regularly in folklore and tales of the supernatural. In Robert Louis Stevenson’s short fable The Song of the Morrow (1896), when the King’s daughter and her nurse go to “that part of the beach were strange things had been done in the ancient ages, lo, there was the crone, and she was dancing widdershins.” At the same time, ominously, “the clouds raced in the sky, and the gulls flew widdershins” too.

Wifie (noun) – not a ‘wife’ as you might think, but a woman in general. However, as a conversation I’ve seen on Quora delicately puts it, it’s usually a term for ‘a woman of uncertain age, but probably past the first flush of youth’.

Winch (verb) – to kiss and cuddle or, as folk would say during the time of my misspent youth, to ‘get off with’ someone.

Windae (noun) – window. Windae-hingin’ is leaning out of the window, a windae-stane is a windowsill and a windae-sneck is the catch on a window frame you use to open or close it. Yer bum’s oot the windae is an abusive phrase, basically meaning, “You’re talking rubbish.” And don’t ask about the politically incorrect term windae-licker. This landed maverick Scottish politician George Galloway in hot water when he reacted to a Glasgow Rangers-supporting critic on Twitter with the retort: “You badly need medical help son. Will decent Rangers fans please substitute this windae-licker…?”

© The Belfast Telegraph

Wynd (noun) – like its counterpart Scots words close and vennel, this refers to a narrow lane or alleyway. Though most of the narrow side-streets and alleyways that cut off from the sides of Edinburgh’s historic Royal Mile are called closes, a couple of them have wynd in their name, for example, Bell’s Wynd and Old Tollbooth Wynd,

Yatter (verb) – according to the online Collins Dictionary, this word’s roots are Scottish and it means ‘to talk idly and foolishly about trivial things’.

Yestreen (noun) – yesterday evening or last night. In Robert Burns’ poem Halloween (1785), the granny tells young Jenny, ““Ae hairst afore the Sherra-moor / I mind’t as weel’s yestreen / I was a gilpey then, I’m sure / I wasna past fifteen…”

Yoke (noun) – obviously, this is the crosspiece placed over the necks of a pair of horses or oxen when they’re made to pull a plough. But in a couple of Sots dictionaries, I’ve seen this described as a term for a motor car. I’ve never heard it used in this context in Scotland, though I did so plenty of times in Northern Ireland. An old friend of my father’s once told me that, in his youth, my old man was famous, or infamous, for the cars he drove – they weren’t sleek, fancy or flashy, but the very opposite. “Aye,” mused the friend, “he drove some right clapped-out oul yokes.”

Yous (pronoun) – unlike standard English, Scots differentiates between the second-person singular and plural personal pronouns. Talk to one person, it’s ‘you’ (or ye). Talk to more than one and it’s yous.

And with that… I will wish yous all a merry Burns Night.

P.S. This should be the end of my posts about the Scots language. But, looking at previous entries, I’ve realised there are loads of other Scots words I’ve forgotten to mention. So, in the future, there will undoubtedly be further entries in which I start again at ‘A’ and try to cover all the omissions.

From pixabay.com / © Makamuki0