From pixabay.com / © TheOtherKev

“With the right, it’s always projection.” That’s a sentiment I’ve frequently heard. In other words, right-wingers love to accuse other people of sins that they’re guilty of perpetrating themselves.

For example, the Trump regime has been cracking down on pro-Palestinian protests in American universities, and threatening foreign students involved with deportation, in the name of ‘combatting antisemitism’. But Trump has readily dog-whistled about George Soros conspiracy fantasies; has sat down to dinner with white supremacist and Holocaust denier Nick Fuentes; and claimed that the neo-Nazi Unite the Right movement that marched through Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 chanting ‘Jews will not replace us’ contained among its number some ‘very fine people’.

Elsewhere, Trump’s evangelical-Christian support is always eager to label gay and trans people as a threat to children. Yet by the end of October this year, the journalist Evan Hurst claimed to be following 188 news stories in 2025 whereby “Christian pastors / youth group leaders / priests / Christian school teachers, etc.,… had been accused / caught / arrested for / convicted of abusing kids in some way.” Incidentally, Trump has been mysteriously reluctant to release the files about his former friend, the financier, paedophile and human trafficker Jeffrey Epstein. Some believe this is because Trump features damningly in those files himself.

However, the current kerfuffle between Trump and the British Broadcasting Corporation, the BBC, aka ‘the Beeb’, is surely the most blatant case of the kettle calling the pot black. The BBC is in hot water because of an episode of its current-affairs programme Panorama, broadcast last year. It contained a clip of Trump addressing his supporters in Washington DC on January 6th, 2021 – a crowd that subsequently became a mob and attacked the US Capitol, wanting to prevent Electoral College votes being counted and Joe Biden being confirmed as the new president. Except that Panorama didn’t show one clip as insinuated, but two clips, from moments in Trump’s speech nearly an hour apart. By splicing them together, it’s claimed, the BBC distorted his message and made him sound like he was inciting the crowd to violence.

Well, later, that crowd did behave violently. But Panorama’s critics seem to imply this had nothing to do with Trump. Oh no, sir. No siree.

According to Trump, the BBC “actually changed my January 6 speech, which was a beautiful speech, which was a very calming speech, and they made it sound radical.” The corporation had ‘defrauded the public’. It had lied. Thus, it was Trump’s ‘obligation’ to take legal action against the network and sue them for… one billion dollars.

It’s hilarious to see Trump lose his rag and accuse someone else of lying because, when it comes to telling lies, Trump is the Master of Mendacity, the Pharaoh of Falsehood, the Divinity of Dishonesty, the Deity of Deceit. The Washington Post catalogues him making ‘30,573 false or misleading claims’ during his first presidency alone. By my calculations, if somebody had successfully sued him for a billion dollars for every ‘porkie pie’ he told between 2016 and 2020, he’d have had to shell out a sum of money in 14 digits.

No doubt the BBC was guilty of sloppy, even vindictive (if you can be that towards Trump) journalism with the Panorama episode. But Trump did instigate the Capitol riot. He was impeached for it a week later and would have been convicted if two-thirds of the Senate had voted for it the following month. As it was, a majority of senators voted for his conviction, by 57 to 43, with seven Republican senators voting for it alongside the Democrats. And Wikipedia’s account of the aftermath of the Capitol riot is a reminder of the revulsion just about everyone who wasn’t a diehard Trump supporter felt at the time – no matter how much these days Trump tries to rewrite history about what happened.

© CBS News

His culpability was obvious before January 6th too. The mob was present in Washington DC that day because of Trump’s relentless lies about the 2020 US presidential election being ‘stolen’ from him. The journalist Howard Goodall has compiled the messages he sent out to his followers in the run-up to the gathering, including: “Big protest in D.C. on January 6th. Be there, will be wild…!” “We will never give up. We will never concede…” “We’re going to fight like hell. If you don’t fight, you’re not going to have a country anymore.” If the Trump-BBC spat does end up in court, I’d love to hear his line of argument. “The BBC twisted the truth about me inciting a bad thing that I really did incite.”

One great irony is that Trump has massively benefited from news companies editing his speeches, in that they usually pick out the bits where he sounds vaguely coherent and sane and ignore the lengthy stretches that suggest his brain is rapidly putrefying into a dollop of rancid mush.

For example, this is him havering to the American Business Forum in Miami on November 5th, seemingly unaware of the difference between South Africa and South America: “For generations. Miami has been a haven for those fleeing communist tyranny in South Africa. I mean, if you take a look at what’s going on in parts of South Africa, look at South Africa, what’s going on. Look at South America, what’s going on. You know, I’m not going to — we have a G20 meeting in South Africa. South Africa shouldn’t even be in the Gs anymore because what’s happened there is bad. I’m not going. I told them, I’m not going. I’m not going to represent our country there. It shouldn’t be there. Take a look at what’s happening in different parts of South America….”

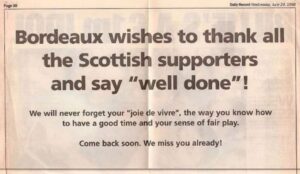

The furore erupted when right-wing British newspaper the Daily Telegraph reported on a leaked memo by Michael Prescott, a one-time political editor for another right-wing British newspaper the Sunday Times and, until recently, an advisor to the BBC’s Editorial Standards and Guidelines Board. Prescott’s memo raised ‘concerns’ about the BBC’s impartiality and cited Panorama’s treatment of the January 6th speech as an example. In the ensuing ruckus, the BBC’s director general Tim Davie and its chief executive Deborah Furness resigned.

It’s rich of the Telegraph to bang on about the BBC’s disingenuity too. According to independent reporter Sam Bright, “in 2025 alone, the paper has been forced to publish over 100 corrections, clarifications, and formal regulatory apologies.” Meanwhile, other right-wing British newspapers soon joined the anti-BBC feeding frenzy, including the Sun (‘BEEB’S BILLION DOLLAR BUNGLE’) and the Times (‘BBC IS TOLD: SAY SORRY OR TRUMP WILL SUE FOR $1BN’). The Sun and the Times’ gaffer is Rupert Murdoch, whose Fox News had to pay 785.5 million dollars in a settlement to Dominion Voting Systems in 2023. This was after Murdoch’s network tried to propagate Trump’s big election lie by accusing Dominion’s voting machines of being rigged to steal the 2020 election from him.

Britain’s right-wing newspapers, of course, are always delighted to see the BBC in trouble. They hate the corporation both out of principle – its publicly-funded existence is an affront to their hardline capitalist ethos – and because of the major competition the BBC’s news operation gives them. No wonder they’re in seventh heaven about Trump bearing down on the Beeb with the threat of a billion-dollar lawsuit.

I also expect that, when the next British general election approaches, the BBC factor will play a part in those newspapers distancing themselves from the beleaguered Conservative Party, whom they’ve traditionally supported. Instead, they’ll swing behind the hard-right Reform party, led by Nigel Farage, who coincidentally is Trump’s number one cheerleader in Britain. If he gets into power, Farage is likely to be as ruthless with the BBC as Trump has been cutting funding for public broadcasting in the USA. No doubt the Telegraph, the Sun and co. see Farage as their best bet for getting rid of their hated rival.

From wikipedia.org / © House of Commons / Laurie Noble

Though its drama, comedy and documentary TV shows were a big influence on me during my formative years, and though it’s Trump who’s persecuting them, I have to admit I find it hard to summon much sympathy for the BBC these days. Its news reporting generally pisses me off for a number of reasons: its much-vaunted ‘impartiality’ (which too often feels like a lily-livered way of not causing offence), its unthinking support of the British establishment and, more recently, its kowtowing to right-wing politicians and opinion-formers.

The news stories on its website often give oxygen to right-wing cranks and extremists – climate-change deniers, anarcho-capitalists, bigots, Trump himself – who are allowed to express their opinions so long as someone else is quoted giving an opposing view. This approach lets the BBC avoid upsetting the cranks and extremists whilst parroting its ‘impartiality’ principle. But as the saying goes, when a journalist finds him or herself in a room with two people arguing about whether or not it’s raining outside, it’s not his or her job to simply write down what both are claiming. The journalist should look out of the window and determine if it is raining or not.

Simultaneously, the BBC is depressingly pro-British establishment. This is most clearly evidenced by the inordinate coverage it devotes to the Royal Family every time one of them dies. Its over-the-top reporting of Prince Philip’s death in 2021 and its ‘perceived attempt to manufacture a largely absent national grief’ drew a record-breaking number of complaints: over 100,000.

Meanwhile, it gives short shrift to anyone threatening to rock that establishment. These include Britain’s trade union movement (one nadir was its coverage of the ‘Battle of Orgreave’ during the Miners’ Strike in 1984, when by reversing footage it suggested the strikers had thrown missiles first and then the police attacked them, when the events had been the other way around); supporters of Scottish independence (during the run-up to the Scottish independence referendum in 2014, the former BBC journalist Paul Mason remarked, “Not since Iraq have I seen BBC News working at propaganda strength like this. So glad I’m out of there“); and left-wing Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn (when BBC journalist Laura Kuenssberg interviewed Corbyn in 2017, the interview was doctored to make it sound like he wouldn’t approve of police using shoot-to-kill tactics to deal with terrorists mounting a 2015 Paris / Bataclan-style attack in Britain).

And, presumably fearful of the future, the BBC has spent recent years grovelling to the right in the hope that it’ll curry favour with them. It never does. Grovelling to bullies simply results in them coming back to inflict more pain on you.

People have lost count of how many times Nigel Farage has been on the Beeb’s flagship political discussion show Question Time, but as of May 2024 it was put at 36. Meanwhile, the BBC’s news agenda slavishly follows that set by the country’s predominantly right-wing press – starting with the round-up of the newspapers on its breakfast-time shows, where viewers are exposed to whatever grievances the likes of the Daily Mail and Daily Express are screaming about that morning. If the corporation had a proper grasp of impartiality (and understood that newspapers with a physical presence on the newsstand aren’t people’s only sources of news), it’d try and balance those headlines with ones from more left-wing, online publications like the Byline Times and Novara Media.

But obviously, I find the BBC’s news coverage more palatable than the biased and often bilious garbage served up by the Mail, Express, Sun and Telegraph.

Interestingly – and I think this is something people in England don’t appreciate – the BBC is possibly the last institution that encourages people in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to feel ‘British’. It’s still present in most people’s homes across the four nations of the United Kingdom. It still gives them some sense of shared British community through its news programmes and its more popular entertainment shows like The Great British Bake-Off. Should the BBC disappear, I don’t see what else, culturally and in the long term, will act as the glue holding the UK together. (Certainly not the family of Mr. Andrew Mountbatten Windsor.) How ironic if the supposed super-British patriot Nigel Farage destroys this glue by abolishing the BBC or underfunding it to the point of irrelevancy.

That is, of course, if Trump doesn’t bankrupt it first.

From pixabay.com / © Ralf Genge