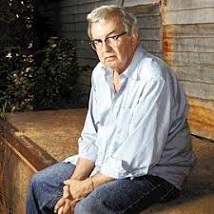

© John Murray

I’ve just finished reading a biography of one of the 20th century’s greatest travel writers, Patrick Leigh Fermor. The biography, Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure, was penned by Artemis Cooper, who’d known him since her childhood, and was published in 2012, a year after his death.

My problem with biographies is that invariably the subjects are, or were, famous and successful. Although I find the story of their fortunes interesting while they’re on the way up, and having to overcome hardships and obstacles, those stories become less compelling when the subjects have achieved success and settled onto a plateau of comfort, wealth and well-being. With Fermor, at least, that secure but less interesting plateau is delayed because his success didn’t really come until when he was middle-aged. And the first 200 pages of this biography, more than half of it, are devoted to Fermor’s youth. Happily, these pages contain the two most dramatic events of his life: the epic trek he embarked on in 1933, at the age of 18, from the Dutch coast to Istanbul; and, while a Special Operations Executive officer during World War II, his heading of a mission in 1944 to kidnap Major General Heinrich Kreipe, commander of German forces on Nazi-occupied Crete.

Furthermore, the number of books Fermor had published in his lifetime barely reached double figures. He also continued to travel. This means that the latter part of Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure, while more sedate, is still interesting because it isn’t just about the boring business of writing.

Cooper is clearly a fan. She admits to once having a ‘schoolgirl crush’ on Fermor and writes early on: “Radiating a joyful enthusiasm, he was one of those people who made you feel more alive the moment he came into the room, and eager to join in whatever he was planning to do…”

However, she quickly acknowledges one of the controversies about Fermor, that he wasn’t adverse to embroidering reality with fantasy in his supposedly factual writing. Sometimes, this was unintentional because he was trying to remember events from decades earlier, but sometimes it happened because, well, the fantasy made for a better yarn. Indeed, Cooper introduces the issue with examples from the early years of Fermor’s life when he was being looked after by a family called the Martins in Northamptonshire, while his real family were in India. The setting was not as bucolic as Fermor liked to recall: “Mr Martin, whom he was later to remember as a farmer, in fact worked at the Ordnance Depot as an engineer and served in the local fire brigade.”

Also, Weedon Bec, the Martins’ village in Northamptonshire, provided Fermor with a startlingly gruesome anecdote that he recounted in his book, A Time of Gifts (1977). At a community bonfire celebrating the end of World War I, “…one of the boys had been dancing around with a firework in his mouth. It had slipped down his throat, and he had died ‘spitting stars’.” However, Cooper notes: “There is no reference to this tragedy in the Northamptonshire Chronicle, nor is it mentioned in the Weedon Deanery Parish Magazine which described the celebrations in considerable detail.”

Similar question marks appear during Fermor’s accounts of his journey to Istanbul in his teens, which are recorded in A Time of Gifts, Between the Woods and the Water (1986) and the posthumously published (and edited by Cooper and Colin Thubron) The Broken Road (2013). I’d known that the material about him crossing the Great Hungarian Plain on horseback in Between the Woods and the Water was suspect – the horse was a fanciful addition to events. However, I wasn’t aware that a memorable scene in The Broken Road was questionable too. According to Fermor in 2003: “Slogging on south, I lost my way after dark, fell into the sea, and waded soaked into a glimmering cave full of shepherds and fishermen – Bulgars and Greeks – for a strange night of dancing and song. It was like a flickering firelit scene out of Salvator Rosa.” Cooper suggests that this incident was really a conflation of two incidents, one of which happened at a later time on Mount Athos. As for the period described in The Broken Road, Cooper states: “At no point in his original account did he walk down this stretch of coast alone, nor did he lose his footing and find himself floundering among freezing rock-pools after dark.”

Unambiguous, though, is the bravery and audacity shown by Fermor and his comrades in wartime Crete. It reflects well on Fermor that he valued the role played by the island’s tenacious resistance fighters in the operation to abduct General Kreipe from under the nose of the German forces he commanded. Indeed, their high-ranking captive was astonished when he found out what was going on. “For Kreipe,” writes Cooper, “being on the other side of the occupation was an eye-opener. He had no idea that the Cretans and the British were working so closely together.”

© The Rank Organisation

Accordingly, Fermor wasn’t pleased at how the operation was portrayed on celluloid, in the 1957 Michael Powell / Emeric Pressburger movie Ill–Met by Moonlight, in which he was played by Dirk Bogarde. Writing to another of the operation’s British participants, Billy Moss, Fermor said of the film: “You and I are perfectly OK, we emerge as charming, intrepid chaps. It’s really the Cretans I’m worried about…” The film’s depiction of the Cretans upset him because it relegated them “to the role of picturesque and slightly absurd foreigners constantly in a state of agitation, coolly managed by these two unruffled and underacting sahibs.”

Thereafter, with Fermor finding his vocation – a slow, gradual progress, because he was anything but a disciplined writer – the book inevitably becomes less eventful. However, there are still some intriguing moments. A trip to the Caribbean brings him into the orbit of James Bond creator Ian Fleming, ensconced in his Goldeneye Estate in Jamaica. I’ve heard speculation that the dashing war-hero Fermor inspired the character of Bond, but at this point Fleming was already “bashing away at a thriller”, the first Bond novel Casino Royale (1953), so Fermor couldn’t have been the original inspiration. However, Fermor’s writings about voodoo, something he became immersed in whilst on the island of Haiti, informed Fleming’s depiction of it in the second Bond novel, Live and Let Die (1954).

Then we get an account of Fermor’s involvement with the 1958 John Huston movie The Roots of Heaven, for which he was commissioned to rewrite Romain Gary’s original screenplay and had to attend several weeks of filming in Chad, Cameroon and the Central African Republic. The film, about “a maverick loner, Morel, who is determined to stop the slaughter of elephants by big game hunters and ivory poachers,” brought Fermor into contact with Trevor Howard, who “drank nothing but whisky from morning till night,” and Errol Flynn, of whom he wrote in a letter, “Errol and I have become great buddies… He is a tremendous shit, but a very funny one…” In a predictable instance of Hollywood hypocrisy, Cooper notes: “Despite the fact that The Roots of Heaven was a plea to save the elephants, John Huston was very keen to shoot one… The back of his Land Rover was an arsenal of shotguns, rifles and ammunition, and it was obvious that he lived not for the film, but to slope off into the bush with a gun.”

© Darryl F. Zanuck Productions / 20th Century Fox

We also hear about Fermor participating in 1972 in a Greek TV programme reuniting the surviving members of the 1944 Kreipe operation. The last participant to come onstage, “to gasps of surprise and a round of applause from the audience,” was the focus of the whole operation, General Kreipe himself. When Fermor asked him in German if he held any grudges about what’d happened, the general gamely replied, “If I had any bad feelings… I wouldn’t be here, would I?”

And we get some short but melancholic accounts of him revisiting eastern Europe during, and just after, Communism. During these visits he tried, often fruitlessly, to track down people and places he’d known during his wanderings through the region in the 1930s. He found one, formerly aristocratic acquaintance in an old folks’ home in Budapest, physically broken and wits wandering. This sad exchange ensues: “‘My old friend Patrick Leigh Fermor lives in Greece.’ – ‘Yes, Elemér, it’s me, it’s Paddy!’ – ‘No, no, you are much too young… But if you go to Greece tell him I’m here, I hope he remembers me.’

Fermor belonged to an era when travelling (for pleasure) and, indeed, writing were largely seen as activities for the upper classes. Thus, certain of his traits can be annoying, traits emblematic of being raised in that privileged stratum of English society: his boundless self-confidence, his shamelessness at making use of the contacts he’s accrued, the fact that he has all those contacts in the first place. This struck me especially when I read Between the Woods and the Water, which sees him stay with a succession of posh eastern European aristocrats and enjoy lavish hospitality that, at times, he seems to think is his entitlement.

Cooper is at least aware of these potential criticisms. Regarding what happens in Between the Woods, she points out: “For his hosts, there was nothing unusual in having guests stay for days or even weeks at a time.” Also: “The greatest blessing that a guest can bring is the right kind of curiosity, and it bubbled out of Paddy like a natural spring…”, which must have been gratifying for his hosts, who by then probably felt like “a useless fragment of a broken empire.” It’s worth mentioning too that Fermor never received a university education which, if it had happened, would presumably have put him among the elite in Oxford or Cambridge Universities and set the seal on him as an establishment figure. Perhaps the fact that the system never fully processed him, and didn’t condition him entirely about what an English gentleman was and wasn’t meant to do, explains why he retained the ‘common touch’ throughout his life. He seemed as much at home blethering with a Macedonian shepherd as he was with a Romanian Count.

If Fermor appears blessed with more than his fair share of luck, it’s probably more to do with Joan Raynor, who became his long-term companion and finally his wife. The daughter of someone who was, successively, a Conservative MP, a First Lord of the Admiralty and a Viscount, she received a private income that enabled Fermor to continue with his travel writing even when he wasn’t reaping great financial rewards from it. She was also broadminded about their relationship, which at times could be described as an ‘open’ one, allowing Fermor to indulge in a few dalliances on the side.

Eventually, the Fermors built a handsome villa for themselves in a rustic part of Greece. As I approached the biography’s last chapters, I wondered how they’d reacted to the country’s growing tourist industry in the late 20th century. Wouldn’t they have been disgruntled at how travellers of a different pedigree from them, folk from less well-off backgrounds intent on getting a week’s break in the sun rather than on experiencing the glories of Greek culture and history, were swamping the beauty spots of their adopted home? But the changes caused by mass-tourism seemed not to impinge on their idyll. Neither did they object to their Greek neighbours making some money out of it. In fact, the building of a hotel nearby seems to have come as a relief to them. Their villa was frequently crowded with guests and now they could farm some of them out to the new establishment.

It must have been tempting to portray Fermor simply as an unstoppable force of nature / Renaissance man-of-action. To her credit, Cooper admits that while he had many admirers, he didn’t charm everyone. Turning up in Athens in 1935, he soon got an invitation from the son of the British ambassador to stay at the embassy. But the ambassador himself proved “quite immune, if not allergic, to Paddy’s high spirits and exotic conversation”, growled at him, “You seem bloody pleased with yourself, don’t you?” and soon gave him his marching orders. Nor was a post-war stint at the British Council in Athens a great success. As one colleague observed, “There was a very insensitive side to Paddy… He was very bumptious, a bit of a know-all, and his enthusiasm and noisiness could be rather wearing.”

While Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure is certainly no warts-and-all exposé, it doesn’t get entirely swept away by the awe-inspiring, larger-than-life aura that Fermor projected. You’re left with the impression of someone who, yes, was remarkable but who, like all of us, sported a few imperfections too. Which actually makes you like him more as a result.

Taken by Joan Leigh Fermor