From wikipedia.com / © Tim Evanson

Today is St Andrew’s Day, the national day of Scotland. So, in keeping with tradition on this blog, here’s the latest instalment in my A-Z of the always-fascinating Scots language….

Once upon a time, the main detractors of the Scots tongue seemed to be those snobby, London-based, Oxbridge-educated fossils who ran Britain’s literary establishment. I’m thinking of the furore that greeted James Kelman’s novel How Late It Was, How Late winning the Booker Prize in 1994. How Late… was written uncompromisingly in the voice of a working-class Glaswegian and its success did not go down well in many posh quarters. Simon Jenkins, for instance, described it getting the Booker as ‘literary vandalism’, Kelman as an ‘illiterate savage’, and the novel itself as “the rambling thoughts of a blind Glaswegian drunk.”

But compare that with the reaction of Britain’s literary establishment to last year’s Deep Wheel Orcadia, the science-fiction verse-novel by Harry Josephine Giles, which is told in Orcadian and which won 2022’s Arthur C. Clarke Award. Deep Wheel Orcadia has been greeted respectfully, for example, here and here, rather than with the horrified pearl-clutching or bemused mockery that used to be the norm.

No, looking at social media, it seems to me that nowadays the folk who bash the Scots language most, and who virulently denigrate people who use it, are Scottish ones – those of a Conservative and / or Unionist disposition. The more extreme members of this faction profess to be loyal subjects of ‘the King’ (Charles presumably, not Elvis) and staunch supporters of a certain football team in Glasgow. They also slather their Twitter profiles in Union Jacks and, without a shred of irony, declare that they ‘hate nationalism’.

In other words, Scots has become part of a culture war. It’s been aligned with the Scottish independence movement and the independence-seeking Scottish government at one end of the battlefield; while at the battlefield’s other end, Unionists and British nationalists deny that Scots exists or deride it as ‘slang’ or ‘an accent’ or (at best) ‘a dialect of English’. Likewise, they do down any sort of Scottish culture that suggests Scotland is slightly different from England and the inhabitants of Great Britain aren’t just a single, homogenous mass. Hence, you get the likes of Ian Smart, self-styled ‘lefty lawyer’ and ‘Scottish Labour Party hack’, dismissing former Machar (Scotland’s Poet Laureate) and writer-in-Scots Jackie Kay as “a woman from Bishopbriggs, writing doggerel”, and slandering another Scots-using author, Emma Grae, as a ‘white nationalist’.

Scotland’s other language, Gaelic, gets it in the neck from these types all the time too. Witness the celebrated episode where right-wing Scottish troll Effie Deans complained on social media about how road-signs in Gaelic caused her to get lost in the Fort William area. This was despite the place-names being printed in English as well as in Gaelic on the signs. “She’s like a post-imperial psychotic satnav gone wrong,” commented one wit on Twitter.

Anyway, here’s a further selection of my favourite words in Scots, this time those beginning with the letters ‘I’, ‘J’, ‘K’ and ‘L’. And Scots is a language. If you don’t like that assertion, you can stick it up your hole.

From google.com/maps

Inch (n) – not the unit of measurement but a geographical word with two meanings, both of which turn up in Scottish place-names. It can be a small island (see Inchmurrin in Loch Lomond, which is actually the largest freshwater island in the British and Irish islands), or an expanse of flat ground next to a river (see Markinch in Fife).

Irn Bru (n/adj) – Scotland’s ‘other national drink’, the fizzy, luridly-coloured, non-alcoholic beverage that’s claimed to be both a hangover cure and the only soft drink in the world not to be outsold by Coca Cola in its native country. I’m not sure if either of these claims stands up to scientific scrutiny, but who cares? All right, Irn Bru is a trademark more than a vocabulary item, but I’ve seen it used as an adjective meaning ‘orange’, for instance, as in “the Irn Bru-coloured ex-American president, Donald Trump.”

Jakey (n) – a down-at-heels, worse-for-wear vagrant with an alcohol dependency. The alcohol in question is usually either Buckfast Tonic Wine or Carlsberg Special Brew. The Scottish-based bestselling author J.K. Rowling is sometimes referred to as ‘Jakey Rowling’ by Scottish-independence enthusiasts, irritated at her high-profile support for Scotland remaining part of the United Kingdom during the 2014 independence referendum.

Janny (n) – a janitor. In Matthew Fitt’s But n Ben A-Go-Go (2000), hailed (22 years before Deep Wheel Orcadia) as the first-ever science-fiction novel written in Scots, the main character works as a cyberjanny, ‘cleaning up social middens in cyberspace’.

Jag (n/v) – variously, the painful pricking sensation you get when you touch a thistle-head; a needle-and-syringe injection; a serving of whisky, as in “Wid ye like a wee jag ay Grouse?”; or a supporter of Partick Thistle Football Club, the third football team in Glasgow whose mascot, Kingsley, is the most terrifying sporting mascot in the world. The adjective derived from jag is jaggy. Yes, Kingsley is the world’s jaggiest sporting mascot too.

© Partick Thistle Football Club

Jalouse (v) – to suspect.

Jaup (v) – ‘to splash or spatter’, according to my well-thumbed copy of the Collins Pocket Scots Dictionary. Like a lot of Scots words, I heard this one, or a vowel-altered variation of it, before I even moved to Scotland. While I was living in Northern Ireland as a wee boy, and whenever my mother was frying something in the kitchen, she’d bark at me: “Stay back or ye’ll be japped by the pan!”

Jiggered (adj) – exhausted.

Jing–bang (n) – the lot or ‘every last one’, as in the phrase, “the whole jing-bang ay them”.

Jings! (exclamation) – a mild and very old-fashioned expression of surprise in Scotland. Nowadays, in fact, I suspect there is just one person in Scotland who still says “Jings!” That is Oor Wullie, the dungaree-clad, bristly-haired juvenile delinquent from the Sunday Post comic strip of the same name.

Jobby (n) – a turd. A word much loved by Billy Connolly, as in his routine about the mechanism that expels faecal matter underneath airplane toilets, the jobby–wheecher. (Wheech means to remove something quickly and suddenly.) Incidentally, another Scottish term for excrement found in this region of the alphabet is keech.

Jouk (v) – to duck or dodge. A nice story I’ve heard is that this word found its way to the American south. There, a juke joint became a roughhouse dancing venue where people had to keep jouking this way and that to avoid punches, bottles, etc., thrown on the dance floor. In turn, this led to the machines that played records of the music you heard at such places being called jukeboxes.

From unspash.com / © Max Tcvetkov

Keek (v) – to peep or glance at something. The derivative keeker refers not, as you might expect, to a peeping Tom, but to a black eye.

Ken (v) – to know. Meanwhile, the adjective kenspeckle means ‘well-known’.

Kent yer faither! (idiom) – “(I) knew your father!” In other words, “Don’t give yourself airs and graces because you’re from humble stock, same as the rest of us.” I’ve never heard anyone use this as a putdown, but I’ve heard several folk over the years complain about kent–yer–faither syndrome in Scotland. They felt Scotland was a place where if you managed to improve yourself and be successful, you then had to deal with a bunch of jealous, moaning gits trying to cut you down to size.

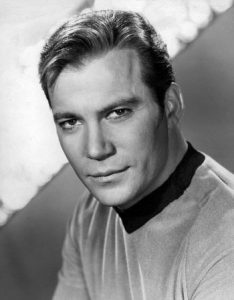

Kirk (n) – with a capital ‘K’, the Kirk refers to the Church of Scotland, i.e., the institution representing the country’s once-dominant Presbyterian faith. With a small ‘k’, a kirk refers to a church building. In 2008, when George Takei, who played Mr Sulu in the original series of Star Trek (1966-69), married his long-term partner Brad Altman and invited all the surviving members of the Star Trek cast to his wedding, except for William Shatner, whom he famously disliked, a joke about this circulated in Scotland. The punchline went: “The Kirk doesn’t approve of gay marriage anyway.”

From wikipedia.org / © NBC

Laldy (n) – ‘your all’. The expression “Gie it laldy!” has been bellowed from the touchline of many a Scottish sports field.

Leid (n) – a language. Thus, this entry is about the ‘gid Scots leid’.

Links (n) – defined in the Free Dictionary as ‘relatively flat or undulating sandy turf-covered ground usually along a seashore.’ A links can also refer to a golf course positioned on such terrain. For example, eastern Edinburgh has Leith Links and Fife has Lundin Links. In fact, Ruth Davidson, the tank-loving honorary colonel who used to lead the Scottish Conservative Party, was ennobled not so long ago and she chose for herself the title of ‘Baroness Davidson of Lundin Links’. Although I prefer to call her: ‘Her Royal Highness Baroness Colonel Tank-Commander Ruth Davidson of Jar-Jar Binks’.

Loon (n) – a word common in North-East Scotland, equivalent to laddie, just as the North-Eastern quine is equivalent to lassie. When I was out drinking as a young guy in Aberdeen, my Aberdonian pal George Boardman would cheerily cry at the end of the evening, “See ye later, loon!”

Loup (v) – to jump.

Lugs (n) – ears. I’ve heard more than one person, after being subjected to someone else’s haranguing or moaning, retort: “Quit burnin ma lugs!”

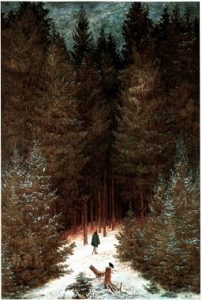

Lum (n) – a chimney. Some years ago, the Guardian reviewed a collection of short stories by the late Scottish author Alasdair Gray and the reviewer complained about the number of typos in the book. He cited as an example ‘Edinburgh lums’, which he assumed was a misprint of ‘Edinburgh slums’. But no, Gray was actually referring to the smoky chimneys of the Scottish capital.

From unsplash.com / © Uwe Conrad