© Producers Releasing Corporation

One thing I’ve tried to do lately is watch more old Hollywood film noirs. When I was a kid, the BBC used to show lots of ones with Humphrey Bogart, so I saw the likes of High Sierra (1941), The Maltese Falcon (1941), The Big Sleep (1946) and Key Largo (1948). But I’m ashamed to say I never got around to watching the many non-Bogey film noirs, even the most famous ones.

Well, with lockdown confining me indoors for a good part of the past year, and with many of these films now in the public domain and available to watch on YouTube or archive.org, there’s been no excuse. I’ve therefore immersed myself in the monochrome 1940s-1950s world of laconic tough guys, slinky femme fatales, guns, hats, raincoats, vintage cars, shadows, cigarette smoke, venetian blinds, whirring fans, neon signs and general, existentialist seediness. (The genre’s great trick was to convince audiences that such a dark, downbeat world existed and yet have most of its films set in an American state as sunny and optimistic as California.)

Here are seven of my favourites…

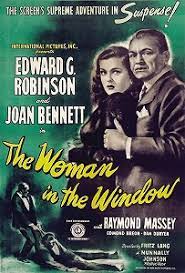

The Woman in the Window (1944)

This little gem is directed by Fritz Lang and stars Edward G. Robinson, who memorably performed in the same year’s Double Indemnity, perhaps the greatest of all film noirs. However, whereas in Double Indemnity Robinson plays somebody investigating a suspicious death and gradually ratcheting up the pressure on the two people responsible for it, in The Woman in the Window the roles are reversed. He plays someone responsible for a death who has the screws tightened on him, first by the police, then by a blackmailer.

Not that Robinson’s character in Woman resembles the smooth, handsome and immoral one played by Fred McMurray in Double Indemnity. He’s a timid college lecturer who sees off his vacationing wife and kids at the film’s start and then retires to his gentlemen’s club, where he’s soon complaining to his buddies (Raymond Massey and Edmund Breon) about being middle-aged, past it and doomed to a life lacking in adventure. Of course, barely has he uttered those words than he’s having an adventure, but not a pleasant one. On his way home, he stops to admire a portrait of a beautiful woman in a shop window, then meets the woman (Joan Bennett) who modelled for the portrait. He gets invited back to her apartment for late-night drinks, unexpectedly meets her jealous and violent admirer (Arthur Loft), and finds himself being throttled. When he tries to fight his assailant off with a pair of scissors, Robinson and Bennett suddenly have a corpse on their hands.

Believing they can avoid involving the police and incriminating themselves, they dump the body out in the countryside. Unfortunately, it transpires that the dead man was more important than they imagined and the District Attorney is soon overseeing an investigation into his murder. And the District Attorney happens to be the Raymond Massey character, one of Robinson’s best mates.

© RKO Pictures

What’s particularly good in this film is Robinson’s mixture of horror and fascination towards Massey’s investigation. He tries to keep clear of it, but at the same time can’t help prying into it – and inevitably incriminates himself a little bit more each time. I also like the juxtaposition between the cosiness of the gentleman’s club with its armchairs, book-lined walls and roaring hearth fires, which symbolises Robinson’s cloistered, middle-aged existence, and the mean streets outside, full of darkness, rainstorms, criminality and – eek! – the possibility of extra-marital sex.

Alas, Woman is spoiled by a ridiculous twist ending, added to wrap up the film on a positive note that would keep the studio (and the Motion Picture Production Code) happy. You might want to stop the film a few minutes before the finish, while things are still looking bleak for Robinson. That way, you’ll have a film noir that’s well-nigh perfect.

Detour (1945)

Film noirs don’t come any more existentialist than Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour, the story of a pianist hitchhiking from New York to Los Angeles to meet up with his lover, a nightclub singer who’s trying to make it in Hollywood, and getting implicated in a couple of murders. It’s ultra-low-budget and a very economical 67 minutes long, but it’s memorable for how it drives home its despairing message. “Fate,” rambles its hapless hero (Tom Neal) in a voice-over, “or some mysterious force, can put the finger on you or me for no good reason at all…”

Even more memorable is its leading female character, Vera (Ann Savage), who’s a femme ferocious rather than a femme fatale. It’s an understatement to say she enters the film halfway through like a force of nature – she’s more like a tornado of rabid dogs. When Neal, driving a car whose real owner inopportunely died a little way back up the road, stops and gives Vera a lift, she soon figures out what’s happened and starts blackmailing him into helping her in her own nefarious schemes. Is there a way he can get the malign Vera out of his life again? There is, but it’s going to make matters even worse…

© 20th Century Fox

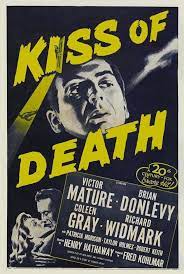

Kiss of Death (1947)

Directed by Henry Hathaway, better known for westerns like 1969’s True Grit, Kiss of Death is a crime melodrama with some suspenseful sequences. For example, there’s the opening scene when anti-hero Nick Bianco (Victor Mature) tries to escape in a maddeningly slow elevator from a jewellery robbery he’s just carried out in the middle of the Chrysler Building; and the climactic one, when Nick has to walk out onto a night-time street and get shot at by his criminal nemesis Tommy Udo (Richard Widmark) because the cops, with whom he’s now colluding, have informed him that they can only arrest Udo if they catch him with a gun in his hand. Both sequences are enhanced by their use of stillness and silence. Mature, the Schwarzenegger / Stallone of his day, didn’t have much range as an actor, but his ruminative passivity is appropriate for the tone here.

Elsewhere, the story of Nick renouncing his criminal ways and turning informer for the Assistant District Attorney (Brian Donlevy), which is his only chance of ensuring a decent life for his two young daughters, is weakened by too much moralising and sentimentality. But it’s a young Richard Widmark as the repulsive Tommy Udo who both steals the show and gives the movie a nasty edge. Pale, irredeemably rotten and cackling like the Joker, he’s put on trial thanks to Nick’s evidence, but gets acquitted and vows revenge on Nick and his kids. We’ve already seen him kill the wheelchair-bound mother of another antagonist by propelling her down a staircase, so we know he means business.

Woman on the Run (1950)

Down-on-his-luck artist Frank (Ross Elliot) is walking his dog one night when he witnesses a murder. The police inform Frank that he’s seen a gangland killing and he’ll be expected to testify in court, so that a major criminal can be locked away. Frank realises this makes him a likely target for the gangsters, decides not to cooperate with the cops and goes on the run instead… And abruptly, the film’s focus shifts to his wife Eleanor (Ann Sheridan). Although their marriage hasn’t been happy, Eleanor embarks on a quest to track Frank down, a quest complicated by the fact that she’s being followed by the cops, a persistent newspaper reporter (Dennis O’Keefe) and probably the villains. During her search, she encounters acquaintances of Frank’s she hadn’t known existed and gradually realises that Frank has been a more affectionate and interesting husband than she gave him credit for.

© Fidelity Pictures Corporation / Universal Pictures

Woman on the Run is a cleverly constructed film that not only wrong-foots the audience by switching attention from its hero to its heroine, but also has a plot containing a personal, emotional journey as well as the usual crime and police shenanigans. It makes good use of its San Francisco locations and portrays the Asian-American inhabitants of Chinatown with slightly more depth than you’d expect of a film of the time. However, my better half, who’s Californian, poured cold water over the film’s climax, which takes place in the amusement park at Ocean Park Pier. This, she pointed out, is actually in Santa Monica, which is a good 340 miles away from San Francisco.

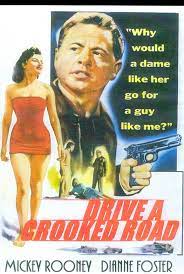

Drive a Crooked Road (1954)

I’d never been much of a Mickey Rooney fan, not when he was playing kids and teenagers in the 1930s and 1940s, nor when he was an all-round entertainer doing Broadway, TV and, in Britain, pantomimes in his old age. However, Drive a Crooked Road offers a fascinating snapshot of Rooney during his career’s low point in the 1950s. By then he was too old to play a youngster anymore, but he was too short to make a conventional leading man. In Drive, he ends up playing a misfit called Eddie Shannon, as lacking in social skills as he is in stature. Eddie’s happier being surrounded by cars than by other human beings and when he isn’t working as a garage mechanic, he drives in small-scale motor races – which, we learn early on, he’s very good at.

One day the glamorous Barbara (Dianne Foster) brings her car to Eddie’s garage for repairs and is soon paying the wee man an inordinate amount of attention. Poor Eddie is astonished – as the film poster puts it: “Why would a dame like her go for a guy like me?” – but can’t help falling for Barbara and daring to dream that their burgeoning relationship is genuine.

© Columbia Pictures

Of course, this being a film noir, it isn’t genuine. Barbara is just bait and Eddie is being reeled into the middle of a plot to rob a bank. Barbara’s real lover, the smug, oily Steve (Kevin McCarthy), plans to use Eddie’s driving skills to transport the stolen money at great speed along a treacherous stretch of road before the police can set up road-blocks. The script, by a young Blake Edwards before he hit paydirt with the Pink Panther movies in the 1960s and 1970s, contains a surprising subtext about social class. Raffishly wearing a yachtsman’s cap (and light-years removed from the panic-stricken everyman that McCarthy would play two years later in Don Siegal’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers), Steve is no criminal low-life but a suave, educated sophisticate. This makes his manipulation of the humble, blue-collar Eddie seem even more loathsome.

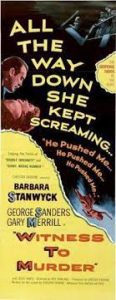

Witness to Murder (1954)

What a difference a decade makes. 1944’s Double Indemnity established Barbara Stanwyck as the imperious queen of film noir, gorgeous, ruthless, happy to use men and dump them whenever it suited her. By 1954’s Witness to Murder, though, Stanwyck was pushing 40 and Hollywood had evidently decided she was better suited to playing dotty, slightly hysterical ladies less in control of their circumstances than they think they are.

Witness unluckily appeared at the same time as Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window and shared a plot component with it: someone looks out of a window, and through someone else’s window, and thinks they see a murder. It was duly dismissed as an interior imitation of the Hitchcock classic, but it’s more interesting than that. Whereas Rear Window dwells on the voyeuristic aspects of spying on other people’s business, Witness merely uses it as a way to kickstart its plot. Cheryl (Barbara Stanwyck) believes she’s seen her neighbour across the street, Albert Richter – an author, a fiancé of a wealthy heiress and a one-time Nazi (but he’s ‘reformed’ now, so that makes him perfectly okay) – murder somebody. The police don’t believe her and when she tries to conduct her own investigations, her sanity is called into question and she even has to spend time in an asylum. All good news for Richter (George Sanders), of course. If everyone thinks this inconvenient witness to his crime is barmy, it won’t be a surprise if sooner or later she ‘appears’ to commit suicide.

Witness to Murder, then, is as much about the unfairness of the era’s gender attitudes as Drive a Crooked Road is about the unfairness of its class attitudes. Stanwyck is sympathetic and engaging, Sanders is predictably as smooth as silk, and it’s nicely wrapped up with a Hitchcockian chase-sequence across the unfinished rooftop of an under-construction high-rise.

Chester Erskine Productions / United Artists

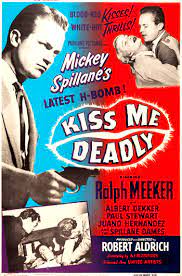

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Directed by Robert Aldrich, scripted by A.I. Bezzerides and based on one of Mickey Spillane’s hardboiled pulp novels about private investigator Mike Hammer, Kiss Me Deadly begins with a startling night-time sequence. Hammer (played by a suitably blunt Ralph Meeker) is out driving, nearly runs over a distraught woman (Cloris Leachman) and reluctantly gives her a lift. He soon finds himself in trouble when bad guys in pursuit of the woman force him off the road. So far, so conventionally noirish. But things get progressively weirder as Aldrich and Bezzerides dump more and more of the Spillane source material and go off and do their own thing.

You don’t get a coherent plot where Hammer moves from A to B and then to C while gradually unravelling the mystery of what happened that night. Rather, names pop up randomly in conversations, names of people who are still alive and who are already dead. Trying to find a common thread, Hammer plods between seemingly arbitrary locales, shabby and smart, old-worldly and 1950s cutting edge: scuzzy hotel rooms and apartments, fancy beach-houses, a boxing gym, an immigrant’s garage, a bigshot’s mansion, a modern art gallery, an opera singer’s quarters crammed with precious vinyl. The threat largely remains anonymous and soon becomes omnipotent. Hammer hears a lot about ‘they’ but can’t identify who ‘they’ are. At the same time, ‘they’ seem able to kill people with a god-like ease and lack of consequence.

Eventually, we learn that the villains are pursuing something contained in a small box, something that’s massively valuable, powerful and potentially destructive, and there ensues an impressively apocalyptic finale. Tapping into the scientific and political fears of an America already immersed in the Atomic Age and the Cold War, and about to embark on the Space Race, Kiss Me Deadly is one of the last entries from film noir’s 1940s-1950s golden age. Indeed, it’s appropriate that by its final scenes, the film seems to have transformed into a newer, more adaptable cinematic genre – science fiction.

Parklane Pictures / United Artists