From pinterest.co.uk

Today, January 25th, 2021, has been designated ‘Gray Day’ on Scottish social media in honour of the celebrated Glaswegian polymath Alasdair Gray, who died in December 2019. As my way of marking the occasion, here’s a reposting of a blog entry I wrote shortly after the great man’s death.

Much has been written about Alasdair Gray, the Scottish novelist, poet, playwright, artist, illustrator, academic and polemicist who passed away on December 29th, 2019. I doubt if my own reflections on Gray will offer any new insights on the man or his works. But he was a huge influence on me, so I’m going to give my tuppence-worth anyway.

In 1980s Scotland, to a youth like myself, in love with books and writing, Gray seemed a titanic cultural presence. Actually, ‘titanic’ is an ironic adjective to use to describe Gray as physically he was anything but. Bearded and often dishevelled, Gray resembled an eccentric scientist from the supporting cast of a 1950s sci-fi ‘B’ movie. He once memorably described himself as ‘a fat, spectacled, balding, increasingly old Glaswegian pedestrian’.

He was also a presence that seemed to suddenly loom out of nowhere. The moment when Gray became famous was in 1981 when his first novel Lanark was published. I remember being in high school that year when my English teacher Iain Jenkins urged me to get hold of a copy and read it. I still hadn’t read Lanark by 1983 when I started college in Aberdeen, but I remember joining the campus Creative Writing Society and hearing its members enthuse about it. These included a young Kenny Farquharson (now a columnist with the Scottish edition of the Times) explaining to someone the novel’s admirably weird structure, whereby it consisted of four ‘books’ but with Book Three coming first, then Books One and Two and finally Book Four. And an equally young Ali Smith recalling meeting Gray and speaking fondly of how eccentric he was.

In fact, I didn’t read Lanark until the following summer when I’d secured a three-month job as a night-porter in a hotel high up in the Swiss Alps. In the early hours of the morning, after I’d done my rounds and finished my chores and all the guests had gone to bed, I’d sit behind the reception desk and read. It took me about a week of those nightshifts to get through Lanark. I lapped up its tale of Duncan Thaw, the young, doomed protagonist of what was basically a 1950s Glaswegian version of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which constituted Books One and Two; and I similarly lapped up its alternating tale of the title character (mysteriously linked to Thaw) in the grimly fabulist city of Unthank, which constituted Books Three and Four. A quote by sci-fi author Brian Aldiss on the cover neatly described Unthank as ‘a city where reality is about as reliable as a Salvador Dali watch’.

© Canongate

That same summer I read The Penguin Complete Short Stories of Franz Kafka (1983) and the fantastical half of Lanark struck me as reminiscent of the great Bohemian writer. Gray himself acknowledged that Kafka’s The Trial (1925), The Castle (1926) and Amerika (1927) had inspired him: “The cities in them seemed very like 1950s Glasgow, an old industrial city with a smoke-laden grey sky that often seemed to rest like a lid on the north and south ranges of hills and shut out the stars at night.”

The result was an astonishing book that combines gritty autobiographical realism with fanciful magical realism. Fanciful and magical in a sombre, Scottish sense, obviously.

With hindsight, Lanark was the most important book in Scottish literature since Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s A Scots Quair trilogy (1932-34). By an odd coincidence I read A Scots Quair four years later when I was working – again – as a night-porter in a hotel in the Swiss Alps. So my encounters with the greatest two works of 20th century Scottish literature are indelibly linked in my mind with nightshifts in hotels decorated with Alpine horns and antique ski equipment and surrounded by soaring, jagged mountains.

Lanark also appeared at a significant time. Three years before its publication, the referendum on establishing a devolved Scottish parliament had ended in an undemocratic farce. Two years before it, Margaret Thatcher had started her reign as British prime minister. During this reign, Scotland would be governed unsympathetically, like a colonial property, a testing ground, an afterthought. So Lanark was important in that it helped give Scotland a cultural identity at a time when politically it was allowed no identity at all.

Whilst telling me about Lanark, Iain Jenkins mentioned ruefully that he didn’t think Gray would ever produce anything as spectacular again. Not only did it seem a once-in-a-lifetime achievement but it’d taken up half of a lifetime, for Gray had been beavering away at it since the 1950s. He once mused of the undertaking: “Spending half a lifetime turning your soul into printer’s ink is a queer way to live… but I would have done more harm if I’d been a banker, broker, advertising agent, arms manufacturer or drug dealer.”

© Canongate

However, two books he produced afterwards, 1982, Janine (1984) and Poor Things (1992), are excellent works in their own rights even if they didn’t create the buzz that Lanark did.

Janine takes place inside the head of a lonely middle-aged man while he reflects on a life of emotional, professional and political disappointments, and masturbates, and finally attempts suicide whilst staying in a hotel room in a Scottish country town that’s either Selkirk or my hometown, Peebles. (Yes, Peebles’ two claims to literary fame are that John Buchan once practised law there and the guy in 1982, Janine might have had a wank there.) The protagonist’s musings include some elaborate sadomasochistic fantasies, which put many people off, including Anthony Burgess, who’d thought highly of Lanark but was less enthusiastic about Janine. However, it seems to me a bold meditation on Scotland in general and on the strained, often hopeless relationship between traditional, Presbyterian-conditioned Scottish males and the opposite sex in particular.

Poor Things, a retelling of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) set in Victorian Glasgow, initially seems very different from Janine but in fact it tackles similar themes. The narrator, Archibald McCandless, relates how his scientist colleague Godwin Baxter creates a young woman, Bella, out of dead flesh just as Frankenstein did with his creature. McCandless soon falls in love with her. There follows a highly entertaining mishmash of sci-fi story, horror story, adventure, romance and comedy, but near the end things are turned on their heads because Bella takes over as storyteller. She denounces McCandless’s version of events as a witless fantasy and portrays herself not as Frankenstein-type creation but a normal woman, albeit one ahead of her time in her views about feminism and social justice. Again, the book is a rebuke of male attitudes towards women, especially insecure Scottish ones that are partly possessive and partly, madly over-romanticised.

© Canongate

Gray’s other post-Lanark novels are entertaining, if less ambitious, and they’re never about what you expect them to be about. The Fall of Kelvin Walker (1985) looks like it’s going to be a comic tale of a Scottish lad-o’-pairts on his way up and then on his way down in London, but it turns into a caustic commentary on the loveless nature of Scottish Calvinism. Something Leather (1990), which is really a series of connected short stories and again features much sadomasochism, isn’t so much about kinkiness as about Gray’s disgust at the politicians and officials who oversaw Glasgow being European City of Culture 1990, something he regarded as a huge, missed opportunity. A History Maker (1994), a science-fiction novel described by the Daily Telegraph as ‘Sir Walter Scott meets Rollerball’, isn’t an absurdist sci-fi romp at all but a pessimistic account of how humanity can never achieve peaceful harmony with nature. And Old Men in Love (2007) promises to be a geriatric version of 1982, Janine, but is really an oddity whose ingredients include, among other things, ancient Athens, Fra Lippo Lippi and the Agapemonites.

Gray was also a prolific short-story writer. He produced three collections of them, Unlikely Stories, Mostly (1983), Ten Tales Tall and True (1993) and The Ends of out Tethers: 13 Sorry Stories and had several more stories published in Lean Tales (1985), alongside contributions from James Kelman and Agnes Owens. I find the quality of his short fiction variable, with some items a bit too anecdotal or oblique for my tastes. But many are excellent and Ten Tales Tall and True is one of my favourite short-story collections ever.

The fact that Gray was also an artist meant that his books, with their handsome covers and finely detailed illustrations, made decorous additions to anyone’s bookcases. The illustration by Gray I like best is probably the one he provided for his story The Star in Unlikely Stories, Mostly.

© Canongate

He also liked to make mischief with the conventions of how books are organised, with their back-cover blurbs, review quotes, prefaces, dedications, footnotes, appendices and so on. For example, he wasn’t averse to adorning his books with negative reviews (Victoria Glendinning describing Something Leather as ‘a confection of self-indulgent tripe’) or imaginary ones (an organ called Private Nose applauding Poor Things for its ‘gallery of believably grotesque foreigners – Scottish, Russian, American and French.’)

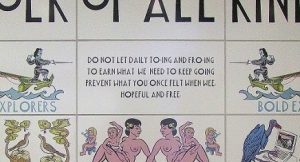

As an artist, Gray was good enough to be made Glasgow’s official artist-recorder in the late 1970s and to enjoy a retrospective exhibition, Alasdair Gray: From the Personal to the Universal, at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in 2014-15. His artwork included a number of murals on the walls of Glasgow and it’s a tragedy that some have been lost over the years. Among those that survive, perhaps the most famous is at Hillhead Underground Station. It contains the memorable and salient verse: “Do not let daily to-ing and fro-ing / To earn what we need to keep going / Prevent what you once felt when wee / Hopeful and free.” Also worth seeing is the mural he painted, Michelangelo-style, on the ceiling of the Òran Mór restaurant, bar and music venue on Glasgow’s Byres Road. It looks gorgeous in the photos I’ve seen of it, although regrettably when I went there with my brother a few years ago to attend a Bob Mould gig, I was already well-refreshed with several pints of beer… and forgot to look upwards.

I never got to meet the great man, though I’m pretty sure I saw him one night in the late 1980s in Edinburgh’s Hebrides Bar, talking with huge animation to a group of friends and admirers. I was, however, too shy to go over and introduce myself.

One writer in whose company I did end up during the late 1980s, though, was Iain Banks, whom I got to interview for a student publication and who then invited me on an afternoon pub crawl across central Edinburgh. Banks was delighted when I told him that his recently published novel The Bridge (1986) reminded me a wee bit of Lanark. “I think Lanark’s the best thing published in Scotland in years!” he gushed. Come to think of it, it was probably the favourable comparison to Gray that prompted Banks to take me on a session.

From austinkleon.com