Once upon a time, the misery involving Scotland and the FIFA World Cup hinged around the fact that, though the Scottish men’s football team usually qualified for the thing, they never, ever managed to progress beyond its first round. This was irrespective of whether they played well (in 1974, managing a win and two draws, one of those draws with Brazil, but going out on goal difference); badly but with a flash of genius when it was too late (in 1978, getting beaten by Peru, drawing with Iran, finally finding their mojo and defeating the tournament’s eventual runners-up Holland, but going out on goal difference); or simply badly (most of the rest of the time).

My family moved from Northern Ireland to Scotland in 1977, in time for Scotland’s campaign in the 1978 World Cup. As I noted above, that performance wasn’t all bad. However, the team’s departure for Argentina, the host country, had been accompanied by a Scotland-wide tsunami of insane expectation and over-optimism. The madness was caused by some witlessly hopeful predictions from Scotland manager, Ally MacLeod, which an irresponsible and headline-hungry Scottish press had amplified. (The team had some good players, but not that good.) When their country didn’t win the World Cup, as everyone had been braying they would, but flopped in the first round, the Scots treated it as a national humiliation. And for years, if not decades, afterwards, they suffered from Post-Ally-MacLeod-Stress-Disorder.

During the 1982 World Cup, I was working in Northern Ireland. I got caught up in the euphoria of Northern Ireland’s unexpected and brilliant run in it – they got past the first round and beat host nation Spain along the way – and, probably fortunately, I didn’t have to focus too much on Scotland. By 1986, I was studying in Aberdeen. For Scotland’s final first-round match of that competition, in Mexico, they needed to beat Uruguay by at least two goals. A mate called Alan Kennedy invited me and a few others to his house to watch the game on TV. For the occasion we ordered a keg of beer and tucked into it several hours before the kick-off. Well lubricated, I dozed off in an armchair not long into the match. What a lucky man I was.

Four years later, in 1990, I was working in Hokkaido in northern Japan. This time, with the World Cup taking place in Italy, I invited a few of my friends to my apartment for Scotland’s final first-round game. Their campaign had begun with another gut-wrenching, soul-destroying defeat – by Costa Rica – that added yet more scars to the nation’s psyche. But then they’d beaten Sweden and now they needed to see off Brazil. They didn’t. The folk I invited to my apartment for the game consisted of some Japanese colleagues and a football-daft Glaswegian called Bill Quinn. Afterwards, one Japanese colleague remarked, “I’ve never seen anyone look so sad as your friend Mr Quinn when the match finished.”

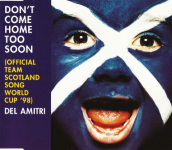

Scotland didn’t qualify for the 1994 World Cup in the USA but made it to the 1998 one in France. By now the nation was well past any delusions that they might come near to winning the damned thing. They just prayed that their team would get past that f**king first round and into the second one. Small wonder that for Scotland’s official 1998 World Cup anthem, the Scottish Football Association got Del Amitri to sing a wistful song called Don’t Come Home Too Soon.

From wikipedia.org / © A&M Records

During this competition I was at my family’s home in the Borders town of Peebles and I watched all three Scotland games in the town’s cosy Bridge Inn, known locally as ‘the Trust’. After the third game, a three-goal humping by Morocco that ensured that, yes, Scotland were coming home too soon, I left the Trust and headed for the Green Tree Hotel at the far end of the High Street. The public bar there was full of people who’d just been watching the game in full regalia – team shirts, tammy hats, tartan scarves and kilts – and whom I expected to be miserable beyond belief. They weren’t. Their team had taken an early bath for the umpteenth time, but what the hell? They’d decided they might as well party. The ensuing evening was one of the best I’ve ever had in a pub. Someone behind the bar stuck on a compilation record called The Best Scottish Album in the World Ever (1997) and I couldn’t believe how many grown men around me knew all the words to Shang-a-Lang (1974) by the Bay City Rollers.

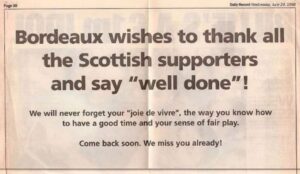

That evening in 1998 was symbolic of what’d happened regarding the Scottish football team and its supporters. While the former seemed doomed to flounder at these big events, the latter had given up on any expectation of their team doing well and were simply determined to enjoy themselves, win, lose or draw. In the process, their self-deprecating humour and dedication to good-natured partying earned them the reputation of being one of the best sets of football fans in the world. For instance, the city council of Bordeaux, where Scotland had played two of their 1998 World Cup games, took out a full-page advert in Scottish newspaper the Daily Record to thank the fans for their behaviour: “We will never forget your ‘joie de vivre, the way you know how to have a good time and your sense of fair play. Come back soon. We miss you already!” I’m sure those sentiments were shared by Bordeaux’s bar and off-licence industry.

Indeed, I felt sorry for bigger countries with a reputation for greater footballing prowess, whose fans did expect them to deliver the goods. I’d see those countries’ fans gather to watch a make-or-break World Cup game… And, when the final whistle blew and their country had messed up, lost the game and exited the competition, those fans immediately headed home with scowls on their faces. Wait, I’d think, aren’t you at least going to hang around and party? (Yes, I’m looking at you, England fans.)

We’re more than a quarter-century on from the 1998 World Cup. The issue with Scotland since then is that they’ve failed to qualify for the competition at all. Bellyaching about them never progressing beyond the first round of it seems like an unobtainable luxury now. We didn’t know how lucky we were back in the late 20th century.

Happily, though, all that has changed. November 18th saw Scotland clinch qualification for next year’s World Cup tournament in Mexico, Canada and the USA by beating Denmark 4-2 at Hampden Park in Glasgow. Sure, Denmark had the lion’s share of the play, and John McGinn was perhaps not being too modest when he commented afterwards, “I thought we were pretty rubbish to be honest, but who cares?” But three of Scotland’s four goals were amazing: Scott McTominay managing to backwards / overhead-kick the ball into the Danish net whilst seemingly levitating in the air; Kieran Tierney sending the ball scouring around the penalty area and just making it inside the Danes’ goalpost; and, with brilliant insouciance, Kenny McLean punting the ball in the final seconds from the halfway line – and seeing it go over the Danish goalie’s head and into the net.

Mads Mikkelsen, your boys took a hell of a beating.

From wikipedia.org / © Luca Faz

My excitement about Scotland being on their way to a World Cup for the first time in 28 years is tempered, though, by the fact that it’s being held in North America. Under the FIFA presidency of Gianni Infantino – a man who’s managed the difficult feat of making Sepp Blatter look wholesome – the sale of tickets has been, in the words of the Guardian, ‘a late capitalist hellscape’ plagued by ‘dynamic pricing, crypto detritus and corporate doublespeak’. How many ordinary Scotland fans, whose presence at past matches has created such a memorable atmosphere, can afford to attend a game? Not so many, I imagine. Plus, if Scotland’s games are played in the USA, the fans will have to get past that country’s increasingly autocratic rules on who gets allowed in. Dare to criticize President Trump on social media and you get barred, apparently. And I’d guess that, online, more than a few Scotland fans have referred to the American Commander-in-Chief as ‘a big orange bawbag’ at some point.

No, I have a horrible suspicion that the majority of Scotland’s support at any USA-held games would consist of well-heeled, conservative and sober Americans who happen to have a ‘Mac’ in their surnames thanks to some Scottish ancestor – folk who like to see a few kilts at their weddings but who quietly prefer American football and baseball to what they call ‘soccer’. The atmosphere at those games could be terribly lame.

That’s on top of my horrible suspicion, based on past experience, that Scotland will screw up against some embarrassing opposition. I have a bad feeling about the Dutch Caribbean island of Curaçao, who have just become the smallest-ever country to qualify for a World Cup, under the management of none other than former Glasgow Rangers boss Dick Advocaat. I can just imagine them ending up in Scotland’s first-round group. And then Scotland making a giant hash of things against them…

Meanwhile, as the USA’s orange Commander-in-Chief loves bragging about his Scottish roots – his mother came from the Isle of Lewis – I bet he’d make a great show of turning up in person to watch any Scottish World Cup game that takes place on American soil. Mind you, he might not survive the ordeal.

From the Daily Record / © Bordeaux City Council