From National Galleries Scotland / © Estate of John Byrne

According to my well-worn copy of the Collins Pocket Scots Dictionary, the word ‘gallus’ means ‘self-confident, daring and often slightly cheeky or reckless.’ Furthermore: “In Glasgow, the word is often used approvingly to indicate that something is noticeably stylish or impressive… The word was originally derogatory and often meant wild, rascally and deserving to be hanged from a gallows.”

So, self-confident, daring, cheeky, reckless, stylish, impressive, wild and rascally? ‘Gallus’, then, is surely the ideal word to describe the work of John Byrne, the Scottish artist, playwright and screenwriter who died at the end of last month aged 83.

Byrne’s art was bright, bold and always good fun. When depicting human subjects, which it usually did, it wasn’t afraid to tip into the realm of caricature. I suppose he could be accused of being a little narcissistic, seeing as his most common subject for portraiture was himself – a retrospective of his work in 2022 exhibited no fewer than 42 self-portraits – but then again, if you’re an artist with an interest in the human visage, your own visage, the one that stares back at you from every mirror, is the most readily available material to work on. Also, Byrne happily treated his own features to the same caricature he did with other subjects, and didn’t flinch from detailing the ravages of time as he passed from youth into middle and then old age.

I particularly like this grizzled and extravagantly moustached self-portrait, which has a skeleton attempting a Muay Thai-type kick against his forehead, presumably in response to the sizeable cigarette he’s smoking. Incidentally, a nicotine yellowness seems to tinge his white whiskers in places.

From wooarts.com / © Estate of John Byrne

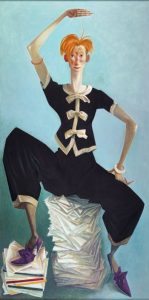

His sense of humour is also apparent in Red and Unread, a portrait of actress Tilda Swinton, who was his partner from 1990 to 2004. At first sight, it looks like Swinton is dancing a hornpipe in a traditional sailor’s outfit. Then you notice the large stack of papers her posterior is resting on and the much smaller stack below her right foot. Byrne meant the big stack to represent the scripts she’d turned down during her career, and the little stack to represent the scripts she’d agreed to do.

From National Galleries Scotland / © Estate of John Byrne

I wonder how differently Byrne’s own career would have gone if a commission he received in the late 1960s had worked out. His early work caught the eye of the Beatles and they asked him to create the cover of their next album, to be called A Doll’s House. Alas, A Doll’s House eventually morphed into 1968’s The White Album and Byrne’s cover was set aside in favour of the famously plain, white one designed by Richard Hamilton and Paul McCartney. At least, a dozen years later, Byrne’s composition was used on the cover of a Fab Four album, the 1980 compilation The Beatles Ballads.

From wooarts.com / © Estate of John Byrne

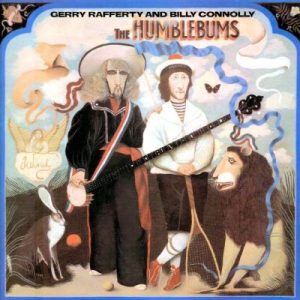

However, shortly afterwards, plenty of other album-work came Byrne’s way, thanks to the patronage of various Scottish musicians: Gerry Rafferty, both solo and with his band Stealers Wheel; Billy Connolly, who started off as a musician who did a little comedy between songs and ended up as a comedian who did a little music between routines; and Donovan. I particularly like this cover for the eponymous 1969 album by the folk-rock band the Humblebums, a partnership between Rafferty and Connolly. This contains the song Her Father Didn’t Like Me Anyway, which I mentioned in my previous post about Shane MacGowan.

© Transatlantic Records / © Estate of John Byrne

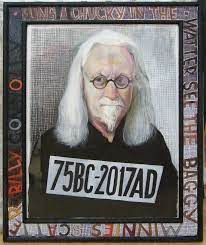

Actually, Billy Connolly was a subject who, over the years, would be depicted several times on Byrne’s canvases. Just three months ago, a mural based on a painting Byrne made of a now bespectacled and white-haired Connolly, and placed on the end of a building in Glasgow’s Osbourne Street in honour of the comedian’s 75th birthday, made the headlines. Developers want to build a new block of 270 students’ flats on the site and plan to cover up the much-loved mural. Aye, students’ flats. I’m sure they’ll look lovely.

From twitter.com/Lost Glasgow / © Estate of John Byrne

From arthur.io / © Estate of John Byrne

Like the Glaswegian artist and writer Alasdair Gray, Byrne was a man of letters as well as one of images and he wrote for the stage and screen. Perhaps he got a taste for stage-writing while working as a designer for Scotland’s legendary 7:84 theatre company during the early 1970s. His best-known plays were the Slab Boys trilogy, whose instalments were first performed in 1978, 1979 and 1982, based on Byrne’s experiences working in a carpet factory near his hometown of Paisley after he’d left school in the 1950s. In 1979, the original Slab Boys also became an episode of the BBC’s Play for Today (1970-84) drama-anthology series, with Gerald Kelly, Joseph McKenna and Billy McColl as the titular slab boys relentlessly flinging jokes, patter and insults at each other in an effort to prevent their work – having to grind and mix colours in a factory basement – from driving them crazy with boredom.

For television, he penned 1987’s tragi-comedy series Tutti Frutti, which helped make a star of Robbie Coltrane. Coltrane plays Danny McGlone, drafted in to sing for an aging Scottish rock ‘n’ roll band called the Majestics after their original singer, Danny’s older brother, dies in a car accident. The Majestics are truly on their last legs, thanks to their delusional guitarist Vincent Driver (Maurice Roëves), who believes himself to be ‘the iron man of Scottish rock’ but whose personal life is a vicious shambles, and the uselessness of the band’s shifty manager Eddie Clockerty (Richard Wilson).

At least Danny finds solace with another new band-member, guitarist Suzy Kettles (played by an also-up-and-coming talent at the time, Emma Thomson). As Danny gradually falls for Suzy, the Majestics go from bad to worse and to beyond worse, with in-fighting, humiliation, depression, knifings, suicide and dental violence – Danny ends up taking a drill to Suzy’s abusive ex-husband, who’s a dentist. Despite the show’s darkness, Byrne’s witty writing makes it hilarious. Tutti Frutti is surely the best thing BBC Scotland has ever produced. Looking at the channel’s woeful output nowadays, it’s probably the best thing it ever will produce too.

© BBC / Estate of John Byrne

A Byrne-scripted follow-up to Tutti Frutti, 1989’s Your Cheatin’ Heart, wasn’t as well-received as the previous show, though it did acquaint him with its star, Tilda Swinton, who’d be his partner for the next 14 years.

Meanwhile, reading the obituaries for Byrne, I’ve only just discovered that he also wrote scripts for the comedy sketch show Scotch and Wry, which showcased the talents of comedian and actor Rikki Fulton and featured such memorable comic characters as insufferable and incompetent Glasgow traffic policeman Andy Ross, aka ‘Supercop’ (“Okay, Stirling! Oot the car!”), and unremittingly miserable Church of Scotland minister the Reverend I.M. Jolly. Scotch and Wry ran for two full seasons from 1978 to 79, its popularity then spawned a series of specials that were broadcast every New Year’s Eve until 1992, and it became a Scottish institution.

And no doubt this Hogmanay, I’ll be raising a glass to the memory of the creative powerhouse that was the gallus John Byrne.

From wooarts.com / © Estate of John Byrne