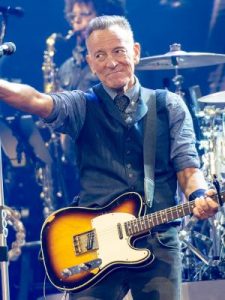

From unsplash.com / © Maryam Sicard

It’s May 22nd, which a quick check on Google informs me is Sherlock Holmes Day, Harvey Milk Day, International Day for Biological Diversity, Buy a Musical Instrument Day, and, thirst-quenchingly, both Chardonnay Day and National Craft Distillery Day. But most interestingly for me, in honour of the planet’s spookiest and blackest-clad musical sub-culture, it’s World Goth Day.

With that in mind, here are YouTube links to a dozen Goth tunes that I’ve been listening to recently. Be prepared, though, for a few annoying YouTube ads for fast-food outlets, perfumes and designer footwear before you get to the delights of the music itself.

First off… I knew nothing about Sidewalks and Skeletons before I stumbled across this number, Born to Die, on YouTube a little while ago. According to a Google search, “Sidewalks and Skeletons is the solo project of UK artist of Jake Lee, who grew up in Bradford, England”. Lee was at one time a deathcore guitarist but during the past two decades has been attracted more by ‘dark electronic music.’ Anyway, as well as being an impressive (if rather intense) listening experience, Born to Die comes with a video that’s a memorable amalgamation of epileptic-seizure-inducing lighting effects and quaint-but-creepy clips from some old, black-and-white silent movies.

Here’s a song called Edison’s Medicine by the San Francisco band In Letter Form. A track on their 2016 album Fracture Repair Repeat, it manages the tricky feat of sounding a bit like late 1970s legends Joy Division, whilst having enough personality of its own to also sound like something other than a song by Joy Division. (There’s a whole sub-genre of bands out there who sound like Joy Division and nothing else – I’m looking at you, Editors – a sub-genre I like to call ‘Joy Revision’.) Anyway, it’s great The only thing to sour the experience of hearing its melancholy gorgeousness is knowing that, tragically, the band’s singer Eric Miranda passed away the same year it was released.

© Sacred Bones Records

And there’s a pleasant (but again not too derivative) Joy Division vibe running through my next choice, Cyaho, by the Belarussian band Molchat Doma. It appears on their 2018 album Etazhi. Popular belief has it that Goth music evolved in wintry, out-of-way cities in northern England in the Margaret Thatcher-dominated 1980s. So perhaps it’s unsurprising that a similar sound emerged from Minsk, the wintry (during the coldest months its temperature drops to minus seven degrees) out-of-the-way capital of Alexander Lukashenka-dominated Belarus. Though apparently, they’re now based in Los Angeles.

If all this Joy Division-influenced music is making you feel glum, here’s the cure. I mean it. Here’s the Cure. In 2000 Robert Smith and co. released their eleventh studio album Bloodflowers, which was greeted by some snotty reviews in the music press. “Goth-awful!” exclaimed the now-defunct Melody Maker, hilariously. What a lot of nonsense. Bloodflowers is a great Cure record. Incidentally, it’s currently the album I listen to most on my elderly iPod while I subject my equally elderly bones and joints to a workout in my local gym. And the very best thing on it is the second track, Watching Me Fall, a mighty, majestic thing indeed. It’s like listening to a Gothicised version of a relentless Led Zeppelin stomper such as When the Levee Breaks (1971) or Kashmir (1975).

My next song is Troops by London-based singer Grace Solero and her eponymous band. It originally appeared on their first album, New Moon, in 2009. I don’t know if Ms. Solero would be pleased to be described as a purveyor of Goth music, but there’s an amount of witchy darkness here, though mixed with some radiant, soaring moments too. In fact, it’s the song’s polarities – its rawness and tenderness – that appeal to me.

There was a time when Australian singer-songwriter Nick Cave, famous for performing with his band the Bad Seeds and for once fronting the raucous punk-Goth outfit the Birthday Party, seemed a Jekyll and Hyde character. Sometimes you’d get Nice Nick, singing gentle, pretty songs like Into My Arms (1997) that you ‘d happily let your granny listen to. Yet you’d also get Nasty Nick, responsible for such sonic assaults as Stagger Lee (1996) where Cave hollered about slobbering on people’s heads and filling them full of lead while Blixa Bargeld shrieked apocalyptically in the background, which you’d only let your granny listen to if you wanted her to die so you could inherit her money.

© Mute Records

Some have lamented the fact that as he’s grown older, Nice Nick has come to dominate Cave’s musical output while Nasty Nick has mostly disappeared. But I just go with the flow… Here’s an example of what I consider Nice Nick at his best, the ballad Sweetheart Come from 2001’s No More Shall We Part. I can’t understand why it hasn’t received more attention, praise and love as I think it’s a marvellous song. Though the lyric “And if he touches you again with his stupid hands / His life won’t be worth living” suggests a smidgeon of Nasty Nick lurking in the mix.

As someone who’s also a fan of heavy metal, I should enjoy the crossover of it and Goth music known as ‘gothic metal’. But with a few exceptions, such as County Suffolk’s awesome Cradle of Filth, the bands don’t appeal to me. HIM, the Rasmus, Nightwish, Charon, Unshine… Their music seems all a bit too tasteful and pretty for my tastes, and the ones with female singers appear to be doing their best to sound like Evanescence, a very successful band who never floated my boat. Plus they all seem to come from Finland – is being a member of a gothic-metal band a prerequisite for getting Finnish citizenship?

However, here’s one Finnish gothic-metal outfit I do like, the melodramatically-named Eternal Tears of Sorrow. This song, Sweet Lilith of My Dreams, the opening track on their 2006 album Before the Bleeding Sun, begins daintily enough, before gathering speed and volume. It’s just a shame that Eternal Tears of Sorrow announced their disbandment three months ago.

And just to show there are gothic-metal bands with female singers whom I like too, here’s Lacuna Coil, from Italy (not Finland). Two years ago, Lacuna Coil played a gig in my current city of residence, Singapore, and I’m still annoyed at myself for missing the opportunity to see them then. This song, Blood, Tears, Dust, from their 2016 album Delirium, nicely combines the operatic vocals of their singer Christina Scabbia with the growlier and more traditionally-metallic tones of their other singer, Andrea Ferro. And musically, it rattles along.

That’s enough about gothic metal. Now it’s time for another hybrid – Goth music blended with twangy surf music. The song in question is from the 2022 EP Surf-Goth by Melbourne artist Desmond Doom and its called Get Me Out. Actually, the dark sounds and dark sensibilities mixed with springy surf guitars put me in mind of some earlier efforts by feedback-loving alternative rockers the Jesus and Mary Chain. (If Jim and William Reid knew I had mentioned the Jesus and Mary Chain in a piece about Goth music, they would probably come around to my house and kill me. So don’t tell them I did that.)

© Desmond Doom Music

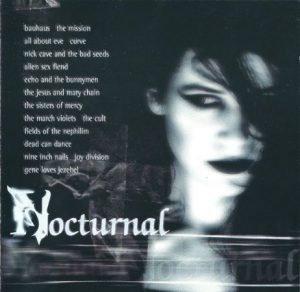

Come to think of it, though, back in 1998 I bought a Goth compilation album called Nocturnal, which had two Jesus and Mary Chain tracks on it… And also on that album, near the end, was my next choice, Big Hollow Man by the singer, producer and artist Danielle Dax. I thought the song was charming, even though it seemed lighter and poppier than most other stuff on the record. But should anyone doubt Ms. Dax’s credentials for appearing in a list of Goth tunes, I’ll point them to the fact that in 1984 she played the wolf-girl in Neil Jordan’s masterly film adaptation of Angela Carter’s short story The Company of Wolves (1979). There’s nothing Gothier than that.

I’ve described the veteran band Killing Joke in the past as a ‘Goth / industrial juggernaut’ with a ‘crunching, thunderous urgency’. The next song, I am the Virus, from Killing Joke’s 2015 album Pylon, does nothing to make me change my opinion of them. With its Beatles-baiting title, it takes retrospective aim at George Bush Jr, Tony Blair, the War on Terror, the second Iraq War et al: “There’s a darkness in the West,” roars singer Jaz Coleman, “oil swilling guzzling corporate central banking mind-f**king omnipotence.” I suppose in 2015 Bush and Blair’s catastrophic intervention in the Middle East seemed the worst thing that could ever happen. Mind you, since then… According to their Wikipedia entry, the band have been ‘inactive’ since the death of guitarist Geordie Walker in 2023. But now, in this dire era of Trump II, I feel we need them more than ever.

Finally, here’s Dead Can Dance, another band who combine Goth music with something else – in their case, ‘world music’, the patronising catch-all term Westerners use to describe traditional music from non-Western countries. Dead Can Dance have been mixing genres enthusiastically since 1996’s Spiritchaser, although on this song, Amnesia, from the band’s 2012 album Anastasis, the world-music elements are less in evidence. Well, apart from the insistent chime of band-member Lisa Gerrard’s yangqin, which Wikipedia describes as a ‘Chinese hammered dulcimer’. Whatever, Amnesia is both a stirring and a wonderfully-mellow composition and it makes a good item with which to end this list.

Happy World Goth Day 2025!

© Procreate