For the last decade I’ve lived in southern and southeastern Asia. During that time, the shadow cast by the tsunami that struck 14 countries on December 26th, 2004, has never seemed far away. Triggered by an earthquake off the coast of Aceh in Sumatra, northern Indonesia, the tsunami claimed approximately 228,000 lives. The worst devastation occurred in Indonesia, Thailand and Sri Lanka, all three countries recording the tsunami as the worst-ever natural disaster in their histories. Today, December 26th, 2024, is the 20th anniversary of the tragedy.

My partner and I lived in Sri Lanka from 2014 to 2022. We weren’t there long before we began to notice memorials to, see lingering traces of and hear people talk about the tsunami, which slammed into the island’s eastern and southern coasts, claimed over 30,000 lives and displaced over 1,500,000 people from their homes.

For instance, in 2020, we stayed briefly in the southern town of Tangalle, where we hired a local tuk-tuk driver, going by the nickname of Dash, to take us to the tourist attractions in the neighbourhood. Dash told us his house had been destroyed by the tsunami and now, 16 years later, he was still trying to build a replacement house further inland. Its ground floor was complete but something had delayed the construction of the first floor.

Also, my work required me to stay a few times in the same hotel in the northeastern town of Trincomalee. There, I got to know the barman, who was a southerner. His tsunami story was that he got trapped by rising waters whilst on a bus east of Galle, southern Sri Lanka’s biggest town. Despite the water, the bus passengers decided it’d be safer to stay on board the vehicle. He disagreed with them, climbed out through a window, started swimming and made it to safety. From what he heard later, he believed the other passengers had died. The disaster disabled the local mobile-phone network and he recalled afterwards having to beg coins off someone, then having to stand in a long, long queue at an old payphone so he could contact his family to let them know he’d survived.

However, what really brought the horror of the tsunami home to us happened while we were having a weekend break in the seaside town of Hikkaduwa in southeastern Sri Lanka. We heard about the village of Peraliya, a few miles up the coast. The statistics of the tsunami’s carnage were so tragically overwhelming that they hid a more particular fact – that because of it, at Peraliya, Sri Lanka also experienced the world’s worst rail disaster.

I’ll let Wikipedia relate the details: “The 2004 Sri Lanka tsunami rail disaster is the largest single rail disaster in world history by death toll… Train #50 was a regular train operating between the cities of Colombo and Matara… On Sunday, 26 December 2004, during the Buddhist full moon holiday and the Christmas holiday weekend, it left Colombo’s Fort Station shortly after 6.50 AM with over 1,500 paid passengers and an unknown number of unpaid passengers with travel passes (called Seasons) and government travel passes…

“At 9.30 AM, in the village of Peraliya, near Telwatta, the beach saw the first of the gigantic waves thrown up by the earthquake. The train came to a halt as water surged around it. Hundreds of locals, believing the train to be secure on the rails, climbed on top of the cars to avoid being swept away. Others stood behind the train, hoping it would shield them from the force of the water…

“Ten minutes later, a huge wave picked the train up and smashed it against the trees and houses which lined the track, crushing those seeking shelter behind it. The eight carriages were so packed with people that the doors could not be opened while they filled with water, drowning almost everyone inside as the water washed over the wreckage several more times. The passengers on top of the train were thrown clear of the uprooted carriages, and most drowned or were crushed by debris…

“…the Sri Lankan authorities had no idea where the train was for several hours, until it was spotted by an army helicopter around 4.00 PM. The local emergency services were destroyed, and it was a long time before help arrived… Some families descended on the area determined to find their relatives themselves. According to the Sri Lankan authorities, only about 150 people on the train survived. The estimated death toll was at least 1,700 people, and probably over 2,000, although only approximately 900 bodies were recovered, as many were swept out to sea or taken away by relatives. The town of Peraliya was also destroyed, losing hundreds of citizens and all but ten buildings to the waves. More than 200 of the bodies retrieved were not identified or claimed, and were buried three days later in a Buddhist ceremony near the torn railway line.”

Today, when you enter Peraliya along the coastal road from the south, you’ll see a monument to the victims called Tsunami Honganji Viharaya on the right-hand, inland side. It consists of an 18.5-metre-high Buddha statue rising from an islet in a rectangular pond, built on the spot where the tragedy occurred. Although the statue was erected with donations from Japan, it’s actually a reproduction of one of the Bhamian statues in Afghanistan that were dynamited and destroyed by those ignorant bigots in the Taliban in 2001.

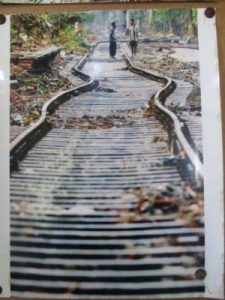

When we visited the monument, there was – and perhaps still is – a small building by the entrance with the words TEMPLE OFFICE painted on its side. Inside, we found a gallery of photographs taken in the tsunami’s immediate aftermath. Some of them recorded such carnage they were difficult to look at. Among the less graphic photographs, one showed the local rail-tracks after they’d been twisted into steel squiggles by the strength of the water.

A little further, on the road’s left-hand, seaward side, there’s a non-religious memorial to the victims, consisting of a plaque, a column and a scene carved onto a wall of grey and rust-orange stone representing the destruction immediately after train and village had been hit. It shows piles of bodies, masonry and smashed palm trees, sections of wrenched-up and misshapen rail track, and upended train carriages, some with corpses hanging from their windows. It’s startlingly candid – indeed, it probably shocks some Westerners, accustomed to such memorials in their own cultures avoiding explicit details and being discretely abstract, so as not to upset traumatised survivors and grieving relatives.

The 2004 tragedy at Peraliya has two poignant footnotes. The locomotive that’d been pulling the carriages, and two of the carriages themselves, were eventually retrieved from the disaster scene, rebuilt and repaired and now, every year on December 26th, they return to Peraliya to take part in a religious ceremony held in remembrance of those who lost their lives. Secondly, one of the small number of survivors was a train guard called W. Karunatilaka. His sense of duty was such that following the disaster he continued to work on the Colombo-to-Galle train service. He was still serving on that coastal route in the mid-2010s.

A much more personal record of what the tsunami did in Sri Lanka that day is provided by Sonali Deraniyagala’s memoir Wave (2013). This records how she lost her husband, two sons and parents when the tsunami swept into Yala National Park on the south coast and how she dealt with – often couldn’t deal with – the emotional and psychological devastation that followed. Indeed, the ‘wave’ of the book’s title may refer to the massive grief she felt during the ensuing years as much as to the tsunami itself. I found the book a tough read indeed. However, it’s worth noting William Dalrymple’s appraisal of Wave when he reviewed it for the Guardian. It was “…possibly the most moving book I have ever read about grief, but it is also a very, very fine book about love. For grief is the black hole that is left in our lives when we lose someone irreplaceable…”

I only realised a few days ago that the 20th anniversary of the tsunami was coming up. By a coincidence, my partner and I spent a pre-Christmas holiday in Khao Lak, the part of Thailand that suffered most in 2004. The area’s death toll was officially 4000, though unofficial estimates put the figure higher. We learned that a tsunami museum had opened in 2022 in the nearby village of Ban Nam Khem and decided to visit it.

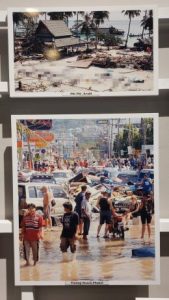

Ban Nam Khem Tsunami Museum manages to be informative about 2004’s events, and convey their dreadful emotional impact, without wallowing in the death and horror. For instance, there’s a display of photographs from the disaster’s aftermath, showing scenes of mangled, waterlogged chaos – boats, vehicles, trees, parts of wrecked buildings dumped on top of each other – but the more upsetting images have been pixellated out. One terrifying photo shows the tsunami about to strike a bay, the sea swollen but still weirdly blue, clear and serene-looking, whereas the palm trees on shore are silhouetted against a crashing white wall of foam. On the premises outside the museum-building, the sense of the tsunami’s gargantuan power is reinforced by the presence of two salvaged trawlers. One was smashed a kilometre inland and deposited in the village’s centre, the other ended up with its prow stuck in the roof of a house.

The museum also has an auditorium where visitors can view a film about a Western tsunami survivor, now an adult, but a kid when he holidayed there with his family in 2004, returning to Ban Nam Khem to search for the fisherman who saved him from the post-tsunami floods. It’s obviously highly fictionalised, but at least it tries to show how something positive can develop out of the very worst of situations. The film also serves an educational purpose, warning local children not to be complacent and to take the area’s regular, tsunami-emergency drills seriously.

For me, the museum’s biggest impact comes from its displays of objects salvaged after the tsunami. Again, there are a few big things giving a sense of the huge, brutal force unleashed that day, such as the shattered prow of a boat or a pulverised car that looks like it’s been in a hydraulic compactor. But the small, everyday artefacts have the greatest poignancy: domestic ones (toys, handbags, purses, crockery, chairs, parasols, footballs, shoes), nautical (snorkelling flippers, broken fishing floats, pieces of netting, crab and lobster traps) and cultural (a spirit house, a Buddha’s head, urns, a Christmas tree). The fact that, 20 years on, some items – a portable CD-playing stereo, a manual typewriter, a box radio, a box camera, an adding machine from a shop – have an antiquated look gives the displays the feel of a time capsule. Yet this time capsule is from the moments before disaster struck and countless lives were ended or turned upside-down.

It’s a reminder that, though our brains are hardwired not to think such about things, our safety and security depend upon the whims of nature. And if we’re in the wrong place at the wrong time, we can be suddenly engulfed in tragedy and chaos on a colossal scale – as happened to hundreds of thousands of unfortunate people in this region of the world two decades ago today.