A while ago, my partner and I, plus a friend, paid a visit to The Art of Banksy: Without Limits, an exhibition showcasing the work of the world’s most famous pseudonymous street artist, political activist and general agent provocateur. The exhibition is currently showing at the Fever Exhibition Hall on Singapore’s Scott’s Road and contains more than 200 Banksy-related artworks, prints, sculptures, photographs and film-clips.

Our Without Limits experience began ominously because we arrived there at the same time as several busloads of teenaged pupils from one of Singapore’s international schools. Not only were there a lot of kids crowding the place, but they were all carrying bags and backpacks – this happened in the afternoon and, presumably, they were heading straight home after their visit – which added to the congestion. But to be fair, though these kids were a distraction by dint of their sheer numbers, they were nowhere near as annoying as they could have been. They could have affected a bored, I’m-too-cool-for-this air of nonchalance – behaved liked stereotypical teenaged prats in other words. (I should know. I was a stereotypical teenaged prat once myself.) However, most of them seemed to take a genuine interest in what was displayed around them.

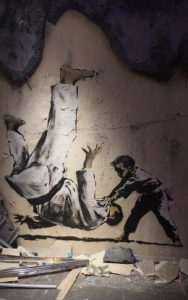

Indeed, I heard some intelligent conversations among them. For example, beside a reproduction of one of seven murals Banksy had done in Ukraine in 2021, showing a little girl upending an adult, judogi-clad martial-arts expert, one young lad explained to his mate how it represented Ukraine’s resistance to the invading, and supposedly vastly superior, forces of Russia. (Putin, of course, claims to be a black belt in judo.) When I saw those throngs of kids at the exhibition’s entrance, I had fears I might end up doing an impersonation of Victor Meldrew. Thankfully, I had no cause to do so.

If you live in the United Kingdom, as I have on and off, you’ll have become accustomed to stories about Banksy and his exploits surfacing now and then in the media: for example, about him circulating fake ten-pound notes bearing the face of Princess Diana; or opening a deliberately-shite theme park called Dismaland Bemusement Park; or having a work fed through a shredder at the very moment it sold for a million pounds at Sotheby’s Auction House. However, I found Without Limits informative because it was the first time I’d seen all these incidents gathered together and given a narrative. The dots had been joined up, creating a proper overview of the guy’s career.

So, having viewed this exhibition, what conclusions can I draw about Banksy? Well, I can’t deny his flair for taking well-worn British symbols and icons, the sort of things you’d see in a London souvenir stall, and subverting them. That’s subverting them in a mild, almost tourist-friendly way so that nobody is offended. Thus, you get a sculpture of a collapsed, partly-folded red British telephone box; or a picture of Queen Elizabeth II sporting Ziggy Stardust’s jagged red-and-blue lightning flash from her brow to her jawline; or one of a Household Cavalryman atop a fairground-carousel horse that’s attached to a giant spring; or one of Winston Churchill with a green Mohican hairdo (actually based on a real incident in 2000, when a May Day protest led to a strip of green turf being plonked on the head of Churchill’s statue in Parliament Square). And, generally, there are plenty of Union Jacks and images of British bobbies on show.

Secondly, I note Banksy’s keen eye – and perhaps perverse love – for the tawdrier aspects of life in 21st-century Britain: what I like to think of as ‘crud Britannia’. This is represented, for instance, by a picture where one of those poor guys frequently seen on Britain’s decaying high streets holding a sign with an arrow and the words GOLF SALE finds himself in front of the column of tanks that advanced on the Tiananmen Square protestors in 1989; or one set in a crumbling English seaside resort where a pensioner sits on a bench oblivious to a circular saw eating its way through the promenade towards him.

Britain’s biggest supermarket, Tesco, may not be pleased to learn that it’s a recurring motif in this regard. There’s a picture where some 1940s, Enid Blyton-style English kids stand to attention by a flagpole, from which a plastic Tesco bag flutters; some Andy Warhol-esque prints of soup cans, only these are cheapo ‘Tesco Value’ ones; and some simple designs where prehistoric, cave-painting figures are shown with shopping trolleys (Tesco ones, no doubt).

And thirdly, you won’t miss Banksy’s leftwing and anti-establishment politics, though of course cynics would argue that by marketing his leftwing, anti-establishment artwork so cannily and successfully, he’s actually thrived in the capitalist system, and its attendant power-structure, that he supposedly disdains. The hardest-hitting work on show is Napalm, a stencil piece showing Phan Thi Kim Phuc – the little girl in Nick Ut’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph The Terror of War, seen running and screaming with severe burns after US forces napalmed her village during the Vietnam War – flanked by and having her hands held by Mickey Mouse and Ronald McDonald. A similar Vietnam-War theme appears in Happy Chopper, wherein a US military attack helicopter is depicted with a giant, pink ribbon below its rotors.

Also anti-establishment is Banksy’s obsession with putting riot policemen in jokey, ironic and disempowering positions. You get a picture of Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz having her basket searched by a thuggish-looking law-enforcement officer; one where a massive cop in armoured combat gear is made to stand splayed against a wall while a little girl in a pink dress frisks him; and a sculpture of a policeman’s head, encased in a helmet that’s been fashioned out of a discotheque mirror-ball.

Without Limits wasn’t perfect. It ran out of steam in its later stages, which I found rather repetitive. Certain key Banksy images appeared again and again… And there’s only so many times that you can look at that Banksy rat, or that masked bloke in the act of throwing a bouquet of flowers, or that little girl with a balloon on a string, without crying ‘Bor-ring’ in the voice of an annoying, nonchalant teenager. Also, I wasn’t impressed by the exhibition shop. I’d seen many cool things that afternoon, but disappointingly the merchandise on sale sported only a few very basic and very familiar Banksy images.

Nevertheless, for the most part, I found Without Limits engaging and entertaining and I’m happy to give it a thumbs-up. Incidentally, if you’re in Singapore and haven’t seen the exhibition yet, you’d better get a move-on – for it ends on April 13th.