© Jonathan Cape

I once read a comment made by esteemed poet Philip Larkin about James Bond’s unsuitability for a short-fiction format: “I am not surprised that Fleming preferred to write novels. James Bond, unlike Sherlock Holmes, does not fit snugly into the short story length: there is something grandiose and intercontinental about his adventures that require elbow room and such examples of the form as we have tend to be eccentric and muted.”

As a boy, I would have agreed. I read most of Ian Fleming’s James Bond books back then and the one I was least enamoured with was For Your Eyes Only. Actually, FYEO (as I’ll refer to it) wasn’t a novel but a collection of short stories featuring Bond. In one of them, Quantum of Solace – which had nothing to do with the 22nd official Bond movie, made with Daniel Craig in 2008 – all 007 did was sit and listen to somebody else narrate a story about a different set of characters.

For me at the age of 11, a good Bond story needed a super-villain with an imposing HQ, and a nefarious scheme involving espionage and / or criminality, and a love interest, and various action scenes where said super-villain tried, unsuccessfully, to bump Bond off. And of course, with Ian Fleming, there’d also be a wealth of background detail culled from Fleming’s experiences as a globetrotting journalist, naval intelligence officer and bon viveur and from his research – research was something he was scrupulous about. Cramming all these things into a short story was not viable, I thought. Thus, the truncated slices of Bondery that appeared in FYEO just seemed weird to me.

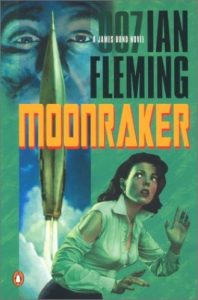

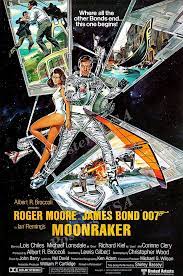

They seem much less weird to me today – especially since, after reading FYEO, I saw such opulent but ramshackle Bond films as The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and Moonraker (1979). Their plots were so disjointed, thanks to the filmmakers’ wish to squeeze in as many different, exotic locations and spectacular action set-pieces as possible, that they often felt like a series of short, barely-connected stories rather than a single, coherent, movie-length one.

Anyway, Larkin wasn’t talking about FYEO but about Fleming’s other collection of James Bond short stories, Octopussy and The Living Daylights, which was published in 1966, two years after Fleming’s death. This book constitutes Bond’s final appearance in print, as penned by his creator. It originally consisted of just the two stories mentioned in the title, although subsequent editions beefed it up with the addition of two more, The Property of a Lady and 007 in New York. Nonetheless, it remains a slim volume. Even with four stories, it comes to a mere 123 pages.

Since then, of course, Octopussy and The Living Daylights have lent their titles to Bond movies, in 1982 and 1987 respectively. A film has yet to be made called The Property of a Lady and to be honest I think Adele or Billie Eilish would have difficulty wrapping their vocal chords around the title in a Bond-movie theme song. (“The proper-TEE… of a lad-EE…!” No, can’t imagine it.) Obviously, 007 in New York wouldn’t cut it as a movie title at all. Mind you, there was a TV movie made in 1976 called Sherlock Holmes in New York starring, heaven help us, Roger Moore as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s deerstalker-wearing detective, so anything is possible.

© Eon Productions

Octopussy and The Living Daylights was one of the few Fleming-Bond books I hadn’t read in my boyhood, so when I encountered a copy of it in a bookstore a while ago thought I’d give it a shot. How would I get on with it? Four decades after I’d read FYEO, would I find the short-story James Bond more palatable?

The opening story, Octopussy, is the longest one in the collection but it has Bond only as a secondary character. The story concerns a Major Dexter Smythe, described acidly by Fleming as “the remains of a once brave and resourceful officer and of a handsome man…” Now “he was fifty-four, slightly bald and his belly sagged in the Jantzen trunks. And he had had two coronary thromboses… But, in his well-chosen clothes, his varicose veins out of sight and his stomach flattened by a discreet support belt behind an immaculate cummerbund, he was still a fine figure of a man at a cocktail party or dinner on the North Shore…”

The North Shore mentioned in that excerpt is the north coast of Jamaica. During the post-war years Smythe and his wife, now deceased, established themselves there after escaping from hard-pressed, austerity-era Britain: “They were a popular couple and Major Smythe’s war record earned them the entrée to Government House society, after which their life was one endless round of parties, with tennis for Mary and golf (with the Henry Cotton irons!) for Major Smythe. In the evenings there was bridge for her and the high poker game for him. Yes, it was paradise all right, while, in their homeland, people munched their spam, fiddled in the black market, cursed the government and suffered the worst winter weather for thirty years.”

Yet this easy, comfortable life in Jamaica didn’t fall into Smythe’s lap. Gradually, Fleming enlightens us on how Smythe was able to afford it. In a back story that has echoes of B. Traven’s 1927 novel and John Huston’s 1948 movie The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, we learn that in the Austrian Alps at the end of World War II, he stumbled across something immensely valuable that he hoarded for himself. To do this, however, he also had to commit murder. Octopussy describes what happens when Smythe’s ‘ancient sin’ finally catches up with him. The bearer of the bad news – that the authorities have found out what he did back in the war and intend to arrest him – is a ‘tall man’ in a ‘dark-blue tropical suit’ with ‘watchful, serious blue-grey eyes’. It’s Bond. But Bond isn’t just carrying out a professional errand. Eventually we discover that he has a personal stake in bringing Smythe to justice.

Once you accept that the story is about Smythe rather than Bond, it proceeds agreeably. The plump and comical Smythe, who paddles about the reef in front of his villa and rather pathetically talks to the fish that swim there – plus an unfriendly, tentacled mollusc whom he’s christened ‘Octopussy’ – gradually loses our sympathy as Fleming peels back the layers and we discover the cruel, and unnecessary, deed he committed to enrich himself decades earlier. Bond is hardly a paradigm of virtue but, equipped with a conscience and a rough-and-ready code of ethics, he’s the antithesis of what’s represented by Smythe. The scene where the flaccid and weak-willed Smythe confesses his crime to Bond is admirably low-key, but Fleming infuses it with a cold, sadistic tension.

The Property of a Lady, on the other hand, is a conventional Bond adventure in miniature. It has 007 turn the auctioning at Sotheby’s of an artwork designed by Carl Faberge – according to the catalogue, “(a) sphere carved from an extraordinarily large piece of Siberian emerald matrix weighing approximately one thousand three hundred carats” – into a trap to catch the KGB’s director of operations in London. Also involved is a female Russian double-agent working in the British Secret Service, whom the service is aware of and uses to feed fake information back to Moscow. To be honest, the plot didn’t make sense to me. I didn’t see how Bond, by snaring London’s top KGB man at Sotheby’s, could avoid alerting Moscow to the fact that British intelligence had cottoned onto the double agent’s existence and were using her for their own ends.

Still, the story is readable and the scenes set in Sotheby’s allow Fleming to show off his knowledge, acquired through research or personal experience, of the world’s most famous broker in fine art. When Bond expresses surprise that the auctioneer doesn’t bang his gavel three times and declare, “Going, going, gone,” an expert informs him, “You may still find that operating in the Shires or in Ireland, but it hasn’t been the fashion at London sales rooms since I’ve been attending them.”

Elements from both Octopussy-the-short-story and The Property of a Lady turn up in Octopussy-the-1982-film, which starred Roger Moore. In the film, the title character is not an octopus but a beautiful and mysterious woman played by Maud Adams, whose father, it transpires, once received a visit from visit by Bond similar to the visit that Major Smythe received in the original story. The film also features a proper octopus, and there’s some business too about a Faberge egg being auctioned off at Sotheby’s. However, if you’ve seen Octopussy-the-movie and don’t remember these things, that’s hardly surprising because it’s a mad mishmash of things – involving nuclear warheads, circuses, exiled Afghan princes, feuding Russian generals, knife-throwing identical twins, hot-air balloons, snake charmers, gorilla suits, everything bar the proverbial kitchen sink. It’s one of the very worst Bond movies in my opinion.

Meanwhile, Hannes Oberhauser, the character murdered by Major Smythe in Octopussy-the-story, plays a small but important role in the backstory of Spectre (2015), the fourth Bond with Daniel Craig in the title role. He’s mentioned in a plot twist that bears upon Bond’s relationship with his old nemesis Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Christoph Waltz). That twist was much derided by the critics, though as a fan of the books I was pleased that Oberhauser got name-checked in a Bond movie at last.

© Eon Productions

The third story in the book, The Living Daylights, sees Bond assigned a mission in Berlin. He has to kill a Soviet sniper whom the KGB have lined up to shoot a defecting scientist while he flees from the east to the west of the city – the story is set shortly before the creation of the Berlin Wall and Checkpoint Charlie. Bond has a crisis of conscience when he discovers that the enemy sniper is a woman, an attractive blonde whom he’s seen posing as a member of an orchestra that’s performing over on the Communist-Bloc side of town. This story is incorporated, more or less intact, into the early part of the 1987 movie The Living Daylights, which was the first one to star Timothy Dalton as Bond. In the film, however, the action is moved to Bratislava, the defector is a KGB officer and his defection is planned to take place during an orchestral performance in a concert hall.

Although the rest of the plot of The Living Daylights-the-film is rather convoluted and unsatisfactory, and there are a few daft moments seemingly left over from the previous movies in the series, it felt like a breath of fresh air to me at the time. It was an attempt at a slightly more sensible Bond film and had an actor in the lead role trying to depict Bond as the moody, occasionally conscience-stricken character that Fleming had originally written. And having a big chunk of Fleming’s story in it at the start definitely helped.

The final story, 007 in New York, is a trifle – Bond is sent into the Big Apple to warn a former Secret Service member that the man she’s cohabiting with is actually a Soviet agent, though he spends most of the story’s eight pages planning the shopping, eating, drinking, clubbing and wenching that he’s going to do while he’s there. This allows Fleming to show off his knowledge of the city – “Hoffritz on Madison Avenue for one of their heavy, toothed Gillette-type razors, so much better than Gillette’s own product, Tripler’s for some of those French golf socks made by Izod, Scribner’s because it was the last great bookshop in New York and because there was a salesman there with a good nose for thrillers, and then to Abercrombie’s to look over the new gadgets… And then what about the best meal in New York – oyster stew with cream, crackers and Miller High Life at the Oyster Bar at Grand Central? No, he didn’t want to sit up at a bar… Yes. That was it! The Edwardian Room at the Plaza. A corner table.”

Fleming was known to have a predilection for sadomasochism, so it’s telling that 007 in New York also sees Bond considering a visit to a bar he’d heard about that “was the rendezvous for sadists and masochists of both sexes. The uniform was black leather jackets and leather gloves. If you were a sadist, you wore the gloves under the left shoulder strap. For the masochists it was the right.” Bond has an old flame in New York whom he intends to meet up with and enjoy some nightlife with, including the S-&-M-themed nightlife, and it’s here that a tiny sliver of 007 in New York makes it into the movies too. The old flame’s name is Solange, which is the name of the character played by Caterina Murino in Casino Royale, which saw Daniel Craig’s debut as Bond, in 2006.

007 in New York is tied up with a gentle, though unexpected, twist that’s worthy of Somerset Maugham – a writer whom Fleming was a big admirer of. And that, unfortunately is it. Fleming had passed away prior to this collection’s publication and no further Bond material was to be published under his name. Thus, Octopussy and The Living Daylights marked the end of James Bond as a literary phenomenon…

For all of two years, until 1968, when Kingsley Amis published Colonel Sun.

© Eon Productions