© Weidenfeld & Nicolson

I’m fairly left-wing in my outlook. But I’m not a fan of recent strategies like cancel culture and no-platforming as ways of dealing with people who express reactionary and offensive opinions.

Partly this is because proponents of cancelling and de-platforming people seem to assume that humanity can be divided neatly into good and bad, with no possibility of various shades of goodness and badness existing in between. I doubt, though, if any human being can honestly claim that they’ve never said or done anything that, later on, they regretted. A case in point is novelist Damian Barr, who got Lady Emma Nicholson removed from the vice-presidency of the Booker Prize due to her hostility towards gay rights, which saw her voting against same-sex marriage in the House of Lords in 2013. Embarrassingly, it then emerged that Barr himself was guilty of tweeting nasty stuff about transsexuals.

Also, I was in favour of letting people with obnoxious opinions get up in public and spout those opinions because of the ‘give-them-enough-rope-and-they’ll-hang-themselves’ argument. Allow them a platform, allow them to speak, and people will realise what offensive tossers they are. However, in today’s media landscape, where Internet algorithms mean folk can spend their entire lives living in online echo-chambers where they hear nothing but their own political viewpoints and have their own prejudices reinforced, I’m less sure of that argument’s validity.

And the dichotomies of cancel culture and no-platforming seemingly leave no room for the potential of human beings to change and improve. I’m from Northern Ireland and the fact that Northern Ireland in 2020 is a better (if still considerably less than perfect) place than it was in, say, 1973 is in part because during the peace process people had to make a leap of faith and accept that characters who’d been banged up in prison for doing some very bad stuff had mended their ways and were worth trusting and negotiating with. I’m thinking of the likes of David Ervine, who was put in the Maze Prison for being in possession of explosives and intent to endanger life but who, when he died in 2007, was hailed by Tony Blair as “a persistent and intelligent persuader for cross-community partnership.”

That said, however, I’m not feeling much sympathy for historian David Starkey, who in a recent interview on Reasoned UK, a platform set up by right-wing foetus Daren Grimes, came out with such jaw-droppers as “Slavery was not genocide. Otherwise, there wouldn’t be so many damn blacks in Africa or in Britain, would there? You know, an awful lot of them survived.” During the ensuing furore, Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam College and Canterbury Christ Church University cut their ties with Starkey and HarperCollins announced that it wouldn’t publish him anymore. Even if Starkey hadn’t expressed himself in such racist terms, I still wouldn’t allow the guy any academic responsibilities because his reasoning suggests that his head’s full of mince. I mean, there are quite a few Jews around these days too. But that doesn’t mean they weren’t subjected to genocide in the past, does it?

It only surprises me that it took Starkey’s horribleness so long to spark an outcry like this, for he’s been farting out offensive and upsetting comments for years on the BBC and in various newspapers. In 2011, for instance, he blamed the London riots on whites who had “become black. A particular sort of violent, destructive, nihilistic, gangster culture…” In 2009, he dismissed Ireland, Scotland and Wales as ‘feeble little countries’ and in 2015 likened the Scottish National Party to the Nazis and the St Andrew’s Cross to the swastika.

From twitter.com/davidstarkeyCBE

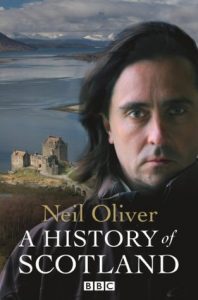

But it isn’t Starkey whom I want to grump about here. It’s another famous tele-historian, Scotsman Neil Oliver (although technically he’s an archaeologist). He’s best-known for his appearances from 2006 to 2010 in the BBC show Coast, in which he tramped around the shores of Britain talking about its natural and human history whilst looking shaggy-haired and hippy-esque, windswept and Celtic, rather like Bono during his Joshua Tree / Rattle and Hum period. Oliver has suffered collateral damage from the Starkey debacle. He was criticised for tweeting Darren Grimes shortly before the catastrophic interview and saying of Starkey, “Tell him I love him, by all means.” Since then, Oliver has nailed his colours to the mast by retweeting sentiments from right-wing reprobates like Douglas Murray, Laurence Fox and Toby Young, who’s opined that Britain is now in the throes of a ‘Maoist Cultural Revolution’. (That’s right, Tobe. Britain, with its Maoist prime minister, Boris Johnson; with its Maoist media publications, like the Sun, Daily Telegraph, Daily Mail, Daily Express and Spectator; and with its Maoist media moguls, like Rupert Murdoch, the Barclay Brothers and the 4th Viscount Rothermere.)

Then the other day, Oliver announced that in September this year he would step down from the presidency of the National Trust for Scotland. The NTS was clearly uncomfortable with Oliver’s association with Starkey and had just issued a statement refuting accusations that their president supported Starkey’s views. For the record, I should say that while Oliver’s politics frequently get up my nose, I don’t believe he’s a racist like Starkey.

I find it peculiar that the NTS made Oliver its president to begin with because it must have alienated a lot of people whom the organisation depends on for support. A staunch red-white-and-blue British unionist down to the split ends of his flowing tresses, Oliver has never made any bones about his disdain for the Scottish National Party – although unlike his pal Starkey, I don’t think he’s ever likened them to Nazis. In 2017, the year he became NTS president and while he was filming a programme in New Zealand, he wrote a piece for the Sunday Times with the title, “In New Zealand, I’ve put enough distance between me and the SNP.” Which was not the most logical thing to say, given that New Zealand is a successful independent country of five million people, which is exactly what the SNP aspire to for Scotland. In early 2020, he wrote in the Times of Scotland’s SNP government: “It’s embarrassing. I think of other nations looking at us and our shenanigans, and shudder with humiliation by association.” This vitriol seems at odds with what Oliver sanctimoniously tweeted two months earlier, on the eve of the December 2019 British general election: “Whatever happens tomorrow, we will still be the same individuals with the same neighbours, living the same lives. Nothing will have changed, not one jot. Peace be with you.”

Presumably, a good number of people in Scotland who are sufficiently interested in Scottish culture and history to pay for NTS membership and donate to it are also people who believe that Scotland should be an independent country again. So by appointing President Oliver, the NTS inadvertently flipped those people the middle finger. If I’m giving money to a cause that suddenly adopts as its figurehead someone who’s very publicly slagged off people like me, I don’t think it’s unreasonable for me to withdraw my patronage.

From twitter.com/N T S

Meanwhile, soon after British protests in support of the USA’s Black Lives Matter movement resulted in the statue of notorious Bristol slaver Edward Colston being pulled down and chucked into nearby Bristol Harbour, Oliver appeared on television and contributed his tuppence worth. For a worrying moment, I actually found myself in agreement with the guy. As he pointed out: “I’m using a smartphone to take part in this conversation… And I know that the cobalt that’s within the battery of my phone and in my laptop computer has almost certainly been mined by a child slave in the Democratic Republic of Congo. And the people who were taking those videos, are taking videos of statues being destroyed… the people holding those phones were probably wearing clothes that had been made in sweatshops in other parts of the world by other living slaves. If this is to be a coming-to-terms with slavery, then I would deal with the plight of slaves who are alive today…”

But just before I punched my fist in the air and shouted, “Yeah, right on, Neil! Smash this globalist capitalist system now!” the hairy bugger went and ruined it. He veered off into a reactionary rant about the protests possibly being “an attempt by anarchists and communists to eat into the built fabric of Britain and thereby to bring down British society.”

In other words, Oliver’s argument about modern-day child slaves was just a piece of whataboutery. He was angry that Colston’s statue got toppled and thrown into the drink, even though Colston’s involvement with notorious slave-traders the Royal African Company saw an estimated 84,000 Africans shipped as slaves across the Atlantic, with 19,000 of them dying en route. So to obfuscate the issue of Colston’s villainy, he introduced the child-slaves of the DRC into the conversation. Yes, child-slaves in 2020! What about them?

Actually, Neil, what about them? Is Boris Johnson and the rest of the gang in charge of the British establishment, which you seem so enamoured with, going to take action against international child slavery anytime soon? I doubt it.

The irony is that the assault on Colston’s statue, which so offended Oliver, a supposed historian, has actually made a lot of people more aware of history. That includes me. For example, soon afterwards, someone on social media suggested removing the statue of Henry Dundas from its column in St Andrew Square in Edinburgh, on account of Dundas being the man who delayed the abolition of Britain’s slave trade by a decade-and-a-half. They also asked whose statue might be put on the column as a replacement. The suggestions on the following thread included names such as Bessie Watson, Jane Haining and Eliza Wigham – whom I had to look up on Wikipedia, because until that point I didn’t know anything about them. (All women, incidentally. Women don’t get much mention in traditional accounts of Scottish history.)

But my concept of history seems to be anathema to Neil Oliver and his mate David Starkey, who see it as a fixed and immutable thing, like lava that spewed out of the great volcano of events and immediately solidified and hardened – becoming a giant monument to be stared at and admired and worshipped, with no room for re-interpretation or re-evaluation. That’s what history is, end of.

This strikes me as an ignorant viewpoint because if we accept history as set-in-stone, we ignore not just possibilities for subjective revision but possibilities for objective revision of it too because, with progress, our science and scholarship for examining the past becomes better. If we didn’t revise our understanding of history from time to time, we’d still be stuck with silly and antiquated notions like, for instance, the Scots being descendants of Scota, daughter of Moses’s Pharaoh, and Geythelos, King of Greece.

But the likes of Oliver and Starkey have no interest in history as a fluid, changing, reviewable thing. No, they’re the contented curators of the dusty, fusty and preserved-in-aspic Museum, or Mausoleum, of Establishment British history. Then again, I suppose it pays their wages.

From commons.wikipedia.org / © William Avery