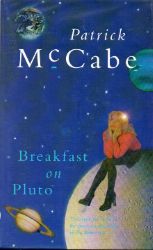

© Pan Macmillan

A month ago, I planned to post something on this blog in honour of the great Irish writer Patrick McCabe, who celebrated his 70th birthday on March 27th. Somehow, though, I forgot all about it and the Happy-Birthday-Patrick post didn’t appear. I must have been distracted by something else near the end of March – probably the latest atrocity or lunacy perpetrated by Donald Trump’s administration in the USA. I can’t remember what. The atrocities and lunacies have come thick and fast since the Orange Jobby’s inauguration as the 47th American president and it’s impossible to keep track of them.

Anyway, here’s that post now. Be warned that it contains many spoilers for McCabe’s books.

Patrick McCabe hails from the town of Clones (pronounced ‘klo-nis’, not as in the 2002 Star Wars movie Attack of the Clones) in County Monaghan, just over the border from Northern Ireland. Clones is famous as the birthplace of boxer Barry McGuigan, known during his pugilistic career as ‘the Clones Cyclone’, though I suspect McCabe was more intrigued by the exploits of another famous, or infamous, native of the town, Alexander Pearce, the convict, serial escapee and alleged cannibal who was hung in Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) in 1824.

Clones and the surrounding countryside are obviously influential on McCabe’s writing and that explains some of the affinity I feel for it – Clones is only a 35-minute drive from Enniskillen in County Fermanagh, where I was born and went to school. Though Clones is in the Irish Republic and Enniskillen is in Northern Ireland, part of the United Kingdom, and as a result the political and cultural vibes aren’t quite the same, there’s nonetheless much in his books I can relate to: how his characters think, behave and speak and how they deal with, or fail to deal with, the frustrations and absurdities that their environment assails them with.

Also, McCabe’s books can be very funny and very dark, frequently at the same time. If there’s anything I find irresistible, it’s the combination of humour and darkness, done well.

The most famous of McCabe’s books is 1992’s The Butcher Boy, which won the Irish Times’ Irish Literature Prize and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Like Alasdair Gray’s Lanark (1981) and Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting (1993), it made such a splash that it both overshadowed his other works and became the measuring stick against which they were all compared. However, while Lanark and Trainspotting were Gray and Welsh’s first published books, The Butcher Boy was McCabe’s fourth. It followed the children’s book The Adventures of Shay Mouse (1985) and the novels Music on Clinton Street (1987) and Carn (1989). That last book is set in a small Irish town, the Carn of the title, that’s clearly a fictional stand-in for Clones and it’s the only one of his early works that I’ve read.

© Picador Books

Actually, I read Carn after I’d read The Butcher Boy, and for a long time I thought it was published after The Butcher Boy too. Maybe Carn feels like a subsequent book because The Butcher Boy is set in the early 1960s, while Carn’s plot spans the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Amusingly, late on, McCabe describes how the townsfolk of Carn have become addicted to the brash American TV soap opera Dallas (1978-91) and are talking about J.R. Ewing and co. as if they’re real people.

Carn tells the tale both of two women, Sadie and Josie, who are trapped in the town in different ways – one drudges in the local meat-packing factory, the other is an outcast who returns after a long exile – and of the town itself, experiencing economic growth in the 1960s, witnessing nearby Northern Ireland going insane in the 1970s, and suffering economic decline in the 1980s. At one point, Josie reflects on the changes, on how “a huddled clump of windswept grey buildings split in two by a muddied main street, had somehow been spirited away and supplanted by a thriving, bustling place which bore no resemblance whatever to it.” Carn isn’t McCabe’s best work, but its blend of sadness, tenderness, bleakness and humour makes it an interesting blueprint for what was to follow.

The Butcher Boy is a more claustrophobic read than Carn because we’re stuck inside the head of its main character, psychotic youngster Francie Brady. Told by Francie in the first person, we quickly realise he’s an unreliable narrator. Indeed, the opening line spells it out: “When I was a young lad twenty or thirty or forty years ago I lived in a small town where they were all after me on account of what I done on Mrs Nugent.” This isn’t unreliable narration in the style of Kazuo Ishiguro where it gradually dawns on you that the reality isn’t quite as it’s being presented. It’s unreliable narration where you know fine well the vile and cruel things that are really going on, despite Francie’s deluded blathering, and you read on with (metaphorically) your fingers over your eyes, waiting for the excruciating moment when the penny finally drops.

This happens several times. Francie’s friendship with a comparatively normal lad called Joe Purcell clearly frays much more quickly than Francie thinks it does. Francie clings to the belief they’re best buddies even when it’s obvious Joe is repelled by the sight of him. Also, after the deaths of his parents, Francie becomes obsessed with a story he’d heard from his father, Benny, about their honeymoon in the seaside town of Bundoran. As Benny told it, he and Francie’s mother were young, beautiful and blissfully in love. We just know from what we’ve seen of Benny, a drunken brute of a man, that the reality was horribly different. Francie, though, believes in the ideal until he finally goes asking questions at the Bundoran boarding house his parents stayed in. Only then does he realise the hideous truth.

© Picador Books

Worst of all is an earlier episode where Francie calms down for a while, works in the local abattoir and lives at home with Benny, who’s – supposedly – still alive at the time. But Benny is oddly subdued and it’s evident to the reader that he’s died of alcoholism and is slowly decomposing into the sofa. Francie, in his madness, doesn’t twig on until several months later when the police come calling.

Incidentally… No disrespect to Patrick McCabe, but I have a wee quibble about the book’s continuity. Francie mentions watching that hoary old American sci-fi TV series Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, which was produced by Irwin Allen and ran from 1964 to 1968. But the book’s later action takes place against the potentially-apocalyptic background of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which occurred in 1962, two years before Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea debuted on television. Maybe McCabe was thinking of the movie that inspired the TV show, released in 1961?

In 1997, The Butcher Boy was filmed by Neil Jordan, a writer-director who with movies like Angel (1982), Mona Lisa (1986) and The Crying Game (1992) has a knack similar to McCabe’s for taking the dreary and mundane and creating something out-of-the-ordinary with it. Though with Jordan, what’s created is closer to magical realism. With McCabe, it’s gothic. The film follows the book fairly faithfully, with a few small embellishments – I liked Sinead O’Connor cameoing as the Virgin Mary. However, just by being a film, it’s a less suffocating experience, as we’re seeing events as bystanders, not inside from the cockpit of Francie’s head. Incidentally, McCabe appears among the cast playing the town drunk, Jimmy the Skite.

© Picador Books

I’ve read claims that Francie’s mental unravelling is meant to symbolise Ireland’s fragile and precarious sense of identity, moving from colonial status to independence and having to navigate such momentous events as the permissive swinging 1960s and the Troubles in Northern Ireland. But to me McCabe’s next book, The Dead School (1995), is more obviously about that. It pits Old Ireland – represented by Raphael Bell, the pious, patriotic and upstanding master of a boys’ boarding school – against Young Ireland – represented by Malachy Dudgeon, a product of a dysfunctional family and a member of a younger, less conservative and more fun-loving generation than Raphael’s. Malachy becomes a teacher and ends up working at Raphael’s school, with disastrous consequences for both of them. Later, when their paths cross again, things are even worse – one is mad, the other an alcoholic. The Dead School describes a collision of two different eras, and two antagonistic Irish mindsets, and the result is as unpretty as The Butcher Boy.

After the darkness of those two books, I was ready for Breakfast on Pluto (1998), which also made it onto the Booker Prize shortlist. This recounts the early-1970s adventures of Patrick ‘Pussy’ Brady, described in contemporary reviews as a ‘gay transvestite’ though now I suppose she’d be called a transwoman. Pussy leaves her Irish hometown and heads to London in search of her biological mother, who’d abandoned her when she was a baby. Overshadowing everything are the Troubles that have recently bloodily erupted in Northern Ireland and are making their presence felt in London too, thanks to bombing campaigns by the IRA. With Irish terrorist violence on the menu, Breakfast on Pluto may not sound a barrel of laughs, but I found it hilarious thanks to Pussy’s droll way of describing things. I also found it curiously uplifting. Despite having many indignities inflicted upon her, Pussy is a trooper who keeps on going.

Breakfast on Pluto was filmed in 2005, again courtesy of Neil Jordan. The movie version is a bit too long and episodic, but it’s mightily enjoyable and has a lighter, breezier feel than the book. Cillian ‘Oppenheimer’ Murphy plays the main character, whose name is changed from ‘Pussy’ to the less provocative ‘Kitten’. This is one of several alterations Jordan makes. Kitten’s first lover – whom McCabe depicted as a crooked Irish politician in the mould of Charles Haughey – becomes a singer in a rock band, played by Gavin Friday, real-life singer of the Virgin Prunes. And generally, Jordan glams things up with some pleasantly nostalgic references to early-1970s popular culture. For instance, the film features both Wombles and Daleks, which I don’t recall being in the original. McCabe has a cameo in this too, playing a schoolteacher who freaks out when the young Kitten asks him for advice on how to have a sex change. Sadly, though, Breakfast on Pluto is one of Jordan’s more underrated and neglected films.

© Picador Books

A year after Breakfast on Pluto, McCabe published a short-story collection, Mondo Desperado. The stories’ titles, like My Friend Bruce Lee, I Ordained the Devil and The Boils of Thomas Gully, tell you what to expect – more of that inimitable McCabe cocktail of the humdrum, absurd, grotesque, macabre and howlingly funny. Deserving special mention is the opening story, Hot Nights at the Go-Go Lounge, which memorably begins: “It’s hard to figure out how in a small town like this a mature woman of twenty-eight years could get herself mixed up with a bunch of deadbeat swingers, but that is exactly what happened to Cora Bunyan and I should know because she was my wife.”

After that, I lost track of McCabe’s books for a while. To date, there’s been seven more I haven’t read: Emerald Gems of Ireland (2001), Call Me the Breeze (2003), Winterwood (2006) – which Irvine Welsh reviewed admiringly in the Guardian – The Holy City (2009), Hello and Goodbye (2013), The Big Yaroo (2019) and Poguemahone (2022). A few years back, however, I did read his 2010 novel The Stray Sod Country, which I thought was wonderful. It features another of McCabe’s exquisitely-drawn Irish small towns. This time, the action takes place mostly in the late 1950s, around the time of the launch of Sputnik 2 in 1957 and the Munich air disaster in 1958 – though there are jumps forward in time to add perspective to the 1950s-set plot.

The Stray Sod Country has an omniscient and sinister narrator. This, we learn, is a malevolent supernatural being called a fetch, which has a dismaying fondness for entering the minds of humans, corrupting them and encouraging them to do harm to others. Sneakily, the fetch foments and escalates feuds between the townspeople. Thus, for example, a rivalry, then hatred, develops between Golly Murray, wife of the town’s barber, and Blossom Foster, wife of its bank manager. Meanwhile, in a fit of priestly jealousy worthy of Father Ted (1995-98), local cleric Father Hand fulminates against his old rival Father Peyton, ‘the infuriatingly smug Mayo toady’, now a ‘celebrity priest of Hollywood, America’ who associates with Frank Sinatra. But he’d be better advised to worry about a disgraced schoolteacher called James A. Reilly. Father Hand had him run out of town for kissing a male pupil. Reilly is living as a vagrant in the nearby bog, nursing his wrath whilst in possession of an Enfield rifle from the Irish Civil War, and he’s fertile ground for the fetch.

I felt McCabe portrayed the cast of small-town eccentrics populating The Stray Sod Country with more affection than usual. And he seemed to have a genuine love for the time and place depicted. Perhaps the great man was mellowing with age?

So, I wish Patrick McCabe all the best as he enters his eighth decade. Barry McGuigan may be the Clones Cyclone, but in literary terms McCabe is the Clones Hurricane – a hurricane of the homespun, the hideous and the hilarious.

© Bloomsbury Publishing