A while ago, I described a visit my partner and I made to one of Singapore’s leading tourist attractions, the Gardens by the Bay. Well, I described half of the visit, because I wrote only about our experiences at the Cloud Forest, a vegetation-draped artificial mountain in the controlled environment of one of the Bays’ two enormous domes. So, here’s an account of our time in the other dome – the Flower Dome.

Having spent the late morning exploring the Cloud Forest, and before spending the early afternoon in the Flower Dome, we had lunch in a Gardens-by-the-Bay food-court called the Jurassic Nest. (The place lived up to its name by having a pair of animatronic dinosaurs on the premises, a brontosaurus and a T-rex, that during our meal came to life, rather feebly, and growled a bit and wagged their heads at one another.) It was here that the Internet coverage on my smartphone suddenly conked out, for the first time in the year since I’d bought it. No amount of fiddling with the settings would get it back online. This was a great nuisance, as I’d paid for entry into the Gardens’ two domes the night before and our e-tickets were in my Googlemail account, which I couldn’t access now. When I tried to access the account on my partner’s phone, I wasn’t allowed in for ‘security’ reasons. Then, just as we were leaving the food-court, and just as I’d resigned myself to having to buy a new pair of tickets for the Flower Dome, my phone’s Internet coverage suddenly and inexplicably returned. We were able to show the original e-tickets at the entrance after all.

That outage was a mystery. I even wondered if the copious water vapour inside the Cloud Forest had affected my phone and temporarily disrupted its online functions. Anyway, on to the Flower Dome…

As domes go, the name ‘Flower Dome’ hardly conjures up the same excitement as, say, Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s (and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s) ‘Pleasure Dome’, or Public Enemy’s ‘Terrordome’, or the third Mad Max movie’s ‘Thunderdome’ (which was presided over by the great, and now sadly late, Tina Turner). And it certainly feels a wee bit less dramatic than the Cloud Forest, which as I said contained its own mini-mountain. The terrain here is relatively flat, though there’s a sunken area in the middle. Spread over this is a host of not only flowers, but also shrubs, trees and other plants assembled from across the world, organised in sections representing ‘gardens’ from South Africa, South America, Australia, California and the Mediterranean.

The first part we explored after going in, up and along to the right of the entrance, was for me the most botanically interesting. This was home to an array of baobabs, a tree I’ve always found fascinating because of its ungainly, bottom-heavy shape – well, I guess that’s why it’s also known as the ‘bottle tree’. This part also featured the oddly named ‘Succulent Garden’, which was full of cacti, plants that hardly seem succulent. The specimens were formidably spiky, thorny and quilled. PLEASE REFRAIN FROM TOUCHING THE FLOWERS said a sign here, unnecessarily.

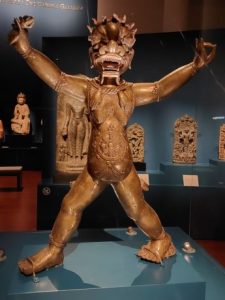

As with the first dome, a variety of wooden statues and carvings, some of them traditional items from indigenous Asian cultures, others more modern in design, were occasionally positioned amid the vegetation. I particularly like the Game–of–Thrones-style dragon perched on top of the knob of a truncated tree-trunk. Later, after I’d descended to the lower level, this dragon looked very impressive seen at a distance and in silhouette.

At the time, the Cloud Forest had been hosting an exhibition relating to the 2022 movie Avatar: The Way of Water, which mainly featured life-sized fibreglass statues of characters and creatures from the movie plonked here and there in the foliage. We were spared the Avatar stuff in the Flower Dome, although another exhibition was in progress – Sakura, which capitalised on Japan’s famous cherry-blossom season, typically occurring between late March and early April. A mock-up of a traditional railway station in the Japanese countryside, with wooden platforms and buildings, had been installed in the lower level and was festooned with pink cherry blossoms. Its ambience would have been charming if the site hadn’t been thronged with people snapping endless selfies of themselves in front of the pretty blossoms. The majority of the culprits, I should add, weren’t members of the usually selfie-daft younger generation. No, the crazed snappers were mostly senior citizens. A few newly-married couples were also using the display as a backdrop for their wedding photos.

Though topographically less spectacular than the Cloud Forest, the Flower Dome’s flatter contours at least allow you to admire the dome itself, curving up over everything like a sky of multi-panelled glass. According to the dome’s webpage, it actually contains 3332 glass panes. It gives an impression of breathtaking spaciousness and it’s no surprise that it’s in the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s biggest greenhouse.