From wikipedia.org / © Eva Rinaldi

Here’s a hypothetical question I’ve heard many times. If you had a time machine, would you travel back in time, find the young Adolf Hitler and kill him? In Stephen King’s 1979 novel The Dead Zone, for instance, the hero puts this question to an old man who lost his son in World War II. The old man replies that he’d stick a knife in Hitler’s heart “as far as she’d go… and then I’d twist her… But first, first I’d coat the blade with rat poison.”

Recently, whilst looking at the dire state of the world and feeling fearful about the future, I’ve wondered about a variation on the time machine / Hitler question. In the future, after manmade climate change has decimated the environment and pig-ignorant ‘populism’ (i.e., fascism) has run society into the ground, who would the remnants of humanity choose to eliminate if they had a time machine and could send an assassin back to, say, the late 20th century? Who would they remove from the timeline in the belief it’d change history for the better? The young Donald Trump? The young Vladimir Putin?

Neither. I suspect those guys would be considered small beer compared to the guy the time-travelling assassin from the future would really go after… Rupert Murdoch.

Murdoch’s media operations have, over the last five decades, caused massive damage to human well-being. He promoted the voracious, greed-is-good, market-über-alles destructiveness of neoliberalism with his support for Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. He’s done his best to ignore, distort and discredit the overwhelming scientific evidence for manmade climate change. Via Fox News, he’s created in the USA a paranoid, xenophobic, extreme-right-wing ecosystem whose millions of inhabitants believe Donald Trump’s lies and will probably vote him again, or someone even worse, into power in 2024 and turn the world’s biggest superpower into an authoritarian state. Yes, Murdoch has seemingly had a finger in everything shit that’s happened in modern history, in everything’s that propelled humanity further down the road to hell. No wonder Murdoch’s son James resigned from the board of News Corp in 2020, sick of the oceans of toxicity created by his father.

It says little for Britain’s newspaper industry that Murdoch owns a swathe of its national titles: the Times, Sunday Times, Financial Times, Sun and Sun on Sunday. These played a prominent role in influencing the 2016 vote on Britain’s membership of the European Union, which led to the economic, diplomatic and cultural shambles of Brexit. No surprise there, either. The ghoulish old Antipodean tycoon once famously remarked that he could intimidate one country’s leader, in No 10 Downing Street, into following his wishes, whereas he couldn’t intimidate the combined might of 28 countries’ leaders represented in Brussels.

From dailysabah.com / © Sun

But Murdoch constitutes just one head of the hydra that is Britain’s predominantly right-wing press. Among the newspapers sold nationwide, only the Guardian, Daily and Sunday Mirrors and Sunday People could be described as having a political stance leaning any way towards the left. Elsewhere, the Daily and Sunday Telegraphs, right-wing and totally honking mad, are owned by the billionaire Frederick Barclay. Resident on the island of Brecqhou, which is administered by Sark in the Channel Islands, Frederick and his late twin brother David once tried to avoid Sark’s tax-inheritance laws by having Brecqhou declared independent of it. That’s ironic considering the Telegraphs’ vehement opposition to Scottish independence.

Another billionaire, the non-domiciled Viscount Rothermere, owns the equally right-wing Daily Mail and Mail on Sunday. About the Mail, I once wrote: “…you might just view the never-ending diet that the newspaper serves up of ignorance, prurience, grubbiness, self-righteousness, hypocrisy, small-mindedness, snobbery, racism, misogyny, Little Englander-ism, xenophobia, Islamophobia, immigrant-bashing, anti-intellectualism, tittle-tattle, curtain-twitching, pseudo-scientific quackery, petty-bourgeois fulmination and general all-round barking right-wing insanity and conclude there’s no hope left for the human race and try to book yourself a one-way passage on the next space probe to Mars.”

And let’s not forget the Daily and Sunday Express, near-clones of the Mail titles, though aimed at an even more demented readership who are additionally obsessed with Madeleine McCann, Princess Diana and the British weather. These used to be owned by millionaire and one-time porno magnate Richard Desmond, but are now the property of Reach plc, which publishes the Mirror. Presumably, Reach hasn’t tinkered with the Express formula because it’s decided to milk those barmy readers for money while they’re still alive.

Over the past few months, Britain’s right-wing newspapers have been fighting the corner of Boris Johnson, ever since they realised the fragility of his premiership. As PM, Johnson hasn’t been so much skating on thin ice as clog-dancing on it. It’s transpired that during the Covid-19 pandemic, when the UK had been put in lockdown, Johnson and his cronies turned No 10 Downing Street into an endlessly partying, boozing frat-house that paid zero heed to the strict non-socialising rules imposed on everyone else. (Intriguingly, Murdoch’s Sun, usually the gobbiest of Britain’s tabloids, has kept relatively quiet about ‘Partygate’, as it’s been dubbed. This may have something to do with James Slack, the Sun’s deputy editor, being Johnson’s Director of Communications at the time when No 10 was boogieing away the lockdown blues.)

The self-serving, scurrilous, mendacious Johnson is a creature of the self-serving, scurrilous, mendacious British press. He started off working at the Times, until he was sacked for fabricating a quote, then found employment as the Telegraph. Max Hastings, then-Telegraph editor, has since said of Johnson: “…he is unfit for national office, because it seems he cares for no interest save his own fame and gratification.” As the Telegraph’s Brussels correspondent, Johnson wrote wildly exaggerated pieces on how the evil EU was imposing spiteful and stupid regulations on plucky little Britain. These helped fuel the Euro-scepticism that birthed the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and eventually won the 2016 referendum in favour of Brexit. No wonder the right-wing press barons love Johnson – he’s one of their own.

From twitter.com/bbcnews / © Daily Mail

Unsurprisingly, their coverage of Partygate, in which they’ve tried to defend and big up the lawbreaking blond oaf, has been nauseating. First, there was the insistence, made most forcibly by the Daily Mail, that Johnson’s breaking of his own Covid laws was unimportant because Russia had just invaded Ukraine and, well, DON’T THEY KNOW THERE’S A WAR ON? More recently, they’ve dedicated their front-page headlines to ‘Beergate’, the hoo-ha over the Labour Party leader Keir Starmer – or, as he’s known in the right-wing press, ‘HYPOCRITE STARMER’ – having a beer and curry at a constituency office in Durham last year while lockdown rules remained in force. Starmer claimed no rules were broken, but the local police have, under pressure from the media, launched an inquiry into the incident. The assumption in the editorial offices of the Mail and the rest is that if Starmer is found to have broken lockdown rules too, their beloved Boris will get off the hook for his own, proven misdemeanours. (He’s already had to pay one fine for a lockdown breach and more fines are likely on the way.)

Starmer has just declared that he’ll resign as Labour Party leader if the police do issue a fine to him over Beergate. This was evidently intended to put some clear, blue, moral water between him and Johnson, already fined but not resigned. However, if he thought this would earn him some credit from the newspapers, he was mistaken. The Mail promptly responded with the headline: STARMER ACCUSED OF PILING PRESSURE ON POLICE.

The more I think about these rags, the more I think of the fable about the frog and the scorpion. The scorpion stings the frog to death, even though this will condemn it to death too, because it’s in its ‘nature’. It’s what it does. It can’t not sting.

The poisonous right-wing nature of much of Britain’s press is a headache for the Labour Party. How can they ever get a fair hearing when those newspapers are programmed to blindly support their Conservative opponents no matter how corrupt, venal and idiotic they become? A quarter-century ago, Tony Blair’s policy on this was to cosy up to them. He got so thick with Rupert Murdoch, the Scorpion King himself, that he became godfather to one of Murdoch’s kids. In return, the headline THE SUN BACKS BLAIR appeared on the front page of Murdoch’s number-one British tabloid prior to the 1997 general election, which saw Blair win power. But such sycophancy has its downside. If you get too close to the likes of Murdoch, you end up either stung to death, like the frog in the fable, or with so much poison in your own system that you become toxic yourself. The latter outcome happened to Blair. I can’t imagine anyone in their right mind describing ‘El Tone’ as a paragon of virtue in 2022.

Still, I don’t have much sympathy either for the supporters of the last Labour Party leader, the atypically left-wing Jeremy Corbyn, who blamed negative British press coverage for all their hero’s woes. Yes, aware that Corbyn represented a threat to the wealthy, powerful interests of their owners, those newspapers bombarded Corbyn with every slur going, that he was a terrorist sympathiser, an anti-Semite, a traitor, whatever. But Corbyn, whom I’ve always regarded as a decent bloke, engineered much of his own bad luck. He was a hopeless communicator. He seemed to be living still in the 1970s, when he’d been a compadre of old school socialist Tony Benn, and never responded to the attacks made against him with the imagination and agility necessary in the changed media landscape of the early 21st century.

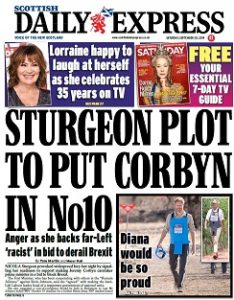

Actually, there’s proof close at hand that, to be successful, a political party doesn’t need to be backed by the majority of newspapers, and can triumph despite most newspapers stinging at it continuously with their scorpion-tails. In Scotland, only one newspaper, the National, supports the Scottish National Party’s policy of Scottish independence. The other Scottish newspapers – north-of-the-border editions of the right-wing ones I’ve just discussed, such as the Scottish Sun and Scottish Daily Mail, and locally published ones like the Scotsman, Herald and Daily Record – oppose the SNP and leap at any opportunity to excoriate it and its leader Nicola Sturgeon. (It’s noticeable how, in the headlines of the utterly wretched Scottish Daily Express, the British PM is always referred to as ‘BORIS’ whereas the Scottish First Minister always gets a contemptuous, misogynistic ‘STURGEON’.)

From bbc.com/ © Daily Express

Yet the SNP have been in power in Edinburgh for the past 15 years and have topped the polls in eight Scottish elections in a row, most recently the council ones on May 3rd that saw them increase their number of councillors by 22. A large part of this is surely down to Nicola Sturgeon herself. Whatever you think of her politics, it’s hard to deny that – unlike Johnson – she speaks like a normal human being, communicates her meaning clearly and generally exhibits some semblance of empathy and integrity. Obviously, this influences a sufficiently large number of Scottish voters, who choose to believe the evidence of their own eyes and ears over the crap they read in the newspapers.

Let’s hope that, when the time comes, British voters as a whole choose to do the same.