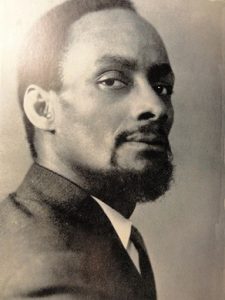

From youtube.com / © BBC

My previous post was about the much-loved Ozzy Osbourne, singer with groundbreaking heavy metal band Black Sabbath in the 1970s, and an ultra-successful solo artist from the 1980s onwards, who died on July 22nd. Here are my favourite dozen songs featuring Ozzy’s vocals.

Black Sabbath (from 1970’s Black Sabbath)

The eponymous first song on Black Sabbath’s eponymous first album, this sets the tone for everything to follow. It immediately establishes a horror-movie vibe, opening with rumbling thunder, sluicing rain and clanging altar bells. Then the doomy chug of heavy guitars and the sepulchral wails of Ozzy’s voice kick in: “What is this that stands before me? Figure in black which points at me-e-ee?” Things eventually speed up for a tumultuous but still menacing climax. (Unsurprisingly, guitarist Tony Iommi and bassist Geezer Butler were horror movie fans and their band’s name comes from a scary film, 1963’s Black Sabbath, directed by the legendary Mario Bava and starring the equally legendary Boris Karloff.)

Incidentally, I like how Ice T uses Black Sabbath for his 1989 track Shut Up, Be Happy. He retains the song’s ominous music but replaces Ozzy’s vocals with the voice of Jello Biafra from the Dead Kennedys, intoning about how America has just been put under martial law: “All constitutional rights have been suspended. Stay in your homes. Do not attempt to contact loved ones, insurance agents or attorneys. Shut up!” Depressingly, Shut Up, Be Happy is more relevant than ever in 2025.

Meanwhile, for a proper cover version of Black Sabbath, I’d recommend the one by goth-metal band Type O Negative on 1994’s Nativity in Black: A Tribute to Black Sabbath, a collection of Sabbath covers whose other contributors include White Zombie, Therapy?, Corrosion of Conformity and Faith No More. It’s not the most the adventurous of covers, but the late Peter Steele’s vocals are suitably foreboding.

© Vertigo / Warner Bros.

Iron Man (from 1970’s Paranoid)

Much loved by Beavis and Butthead, this is the most remorseless and skull-crushing of Sabbath songs. It’s about a man who travels into the future, witnesses the apocalypse, gets turned to steel, then returns to the present to warn humanity but is ridiculed and shunned because he’s now a metallic freak: “Is he alive or dead? Has he thoughts within his head? We’ll just pass him there… Why should we even care?” So, what does he do? He engineers the apocalypse he foresaw: “Heavy boots of lead, fills his victims full of dread…”

I’ll make a confession here. Back in my drunken-asshole student days, I arrived home from the pub one Saturday night and, with one of my flatmates, also a drunken-asshole student, we made a bet while we played the album Paranoid on the flat’s stereo. If we played it at full volume, during which song would another flatmate, a clean-living, go-to-bed-early type, finally lose it, jump out of bed, fling open the door of his room and scream at us to turn it down? You guessed it. While Ozzy was hollering about Iron Man being turned to steel in the great magnetic field, the door of that flatmate’s room swung back and a voice bellowed: “WOULD YOU TURN THAT DREADFUL RACKET DOWN?”

War Pigs (from Paranoid)

A lamentation against war and those who orchestrate it, War Pigs is a reminder that Black Sabbath’s members were youths during the late 1960s when the pacifistic hippy movement was on the go. This being Sabbath, though, War Pigs dwells bitterly on war’s violence and hatred rather than try to counter it with calls for peace and love. It’s a long song, just under eight minutes, yet short on lyrics – the word-count is less than 150. But oh, what words: “Generals gathered in their masses, just like witches at black masses… In the fields, the bodies burning, as the war machine keeps turning…”

This song has seen several notable cover versions. Judas Priest did an impeccably metallic rendition of it – I also like the accompanying video, wherein Priest-frontman Rob Halford stomps about the stage like a farmer in wellies trying to negotiate a boggy field. A funked-up version of it impressively closes the 2023 album On Top of the Covers from singer / rapper T-Pain. But for a reworking of War Pigs that’s splendidly ‘out there’, yet retains the original’s drive and power, you can’t beat what the ‘Ethiopian Crunch Music’ band Ukandanz did to it. They replaced Tony Iommi’s guitar with a saxophone and sang it in Amharic.

© Vertigo / Warner Bros.

Planet Caravan (from Paranoid)

The sublimely dreamy and trippy Planet Caravan has been described as ‘the ultimate coming-down song’. Well, if the stories about how Ozzy and the rest of Black Sabbath were behaving at the time are true, they certainly needed a good coming-down song. To augment the faraway sound, Ozzy sang through a Leslie speaker during the recording, which gave the impression he was warbling the lyrics underwater.

There’s a mellow cover of Planet Caravan at the end of Pantera’s less-than-mellow 1994 album Far Beyond Driven. Indeed, Pantera performed Planet Caravan at the Back to the Beginning concert, Ozzy’s farewell show staged in Birmingham just two-and-a-half weeks before he died.

Children of the Grave (from Master of Reality)

Master of Reality is possibly Black Sabbath’s heaviest and doomiest-sounding album. Its best track, Children of the Grave, has an urgent, unsettling sound that suggests creepy, occult-flavoured goings-on. That feeling is increased by the song’s horror-movie-like title and the way it’s whispered sinisterly during the coda. But if you listen properly to the lyrics, you discover it’s not about the supernatural at all. It’s really another anti-war song, like War Pigs: “Must the world live in the shadow of atomic fear? Can they win the fight for peace, or will they disappear?”

Supernaut (from 1972’s Vol. 4)

The exuberant Supernaut might be, as the lyrics suggest, about a man trying to find “the dish that ran away with the spoon” or “the crossing near the golden rainbow’s end”. Or it might be about, you know, substances. Of which, by then, the band were taking a lot.

For a cracking (and funny) cover version of this song, look no further than the one by 1000 Homo DJs (actually a side-project of the industrial rock band Ministry) which retains the original’s insane jauntiness while spicing it up with a solemn 1960s voice intoning about the dangers of taking acid. For my money, this is the best track on Nativity in Black: A Tribute to Black Sabbath, basically because it’s not afraid to try something different.

© Vertigo

Sabbath Bloody Sabbath (from 1973’s Sabbath Bloody Sabbath)

What can I say? This is my all-time favourite Black Sabbath song – ever, ever, ever.

Symptom of the Universe (from 1974’s Sabotage)

It could be argued that the hectic, exhilarating Symptom of the Universe is a track that helped invent punk rock. And if it didn’t, it surely helped invent thrash metal. Fittingly, the Brazilian thrash metallers Sepultura do a nifty version of this song, which again can be found on Nativity in Black: A Tribute to Black Sabbath.

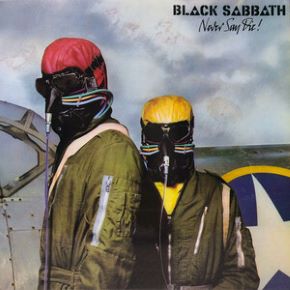

Never Say Die (from 1978’s Never Say Die)

By 1978 the writing was on the wall for Ozzy Osbourne’s association with Black Sabbath. He’d already quit the band briefly (and been replaced, equally briefly, by singer Dave Walker) and Never Say Die would be the final Ozzy-fronted Black Sabbath album until 2013’s 13. Thus, it was recorded under strained circumstances. Never Say Die was badly received at the time, and nowadays it’s fashionable to write it off as Ozzy-era Sabbath’s last, perfunctory gasp. But, if you can handle the ‘jazz inflections’, it’s not a bad album – just different. As the Guardian once said of it, “it’s a quirky and enjoyable record, as long as you don’t expect Sabbath Even Bloodier Sabbath.”

And the title track is a stormer. Ozzy delivers it so directly and defiantly he could be fronting a garage band.

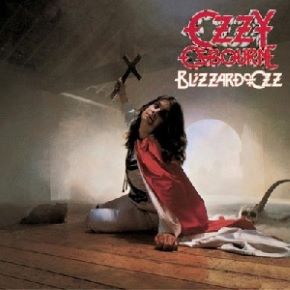

Crazy Train (from 1980’s Blizzard of Ozz)

The second track off Ozzy’s first solo album, this has a cleaner, nimbler guitar sound – courtesy of tragically short-lived guitarist Randy Rhoads – that’s in keeping with the mainstream American glam-metal aesthetic that, for a while, dominated heavy metal in the 1980s. The lyrics begin wholesomely – “Maybe it’s not too late to learn how to love and forget how to hate” – but by the chorus we’re getting a probable summation of Ozzy’s mental state at the time: “Mental wounds not healing, life’s a bitter shame, I’m going off the rails on a crazy train!” (It wasn’t until 1982 that he’d marry the formidable Sharon Arden, the woman who’d, eventually, clean him up, sort him out and reinvent him as an amiable, reality-TV dad.)

© Jet Records

That same year, the now Ozzy-less Black Sabbath released Heaven and Hell, their first album with Ronnie James Dio on vocals. 1980 was also when I entered the ‘senior school’ – fifth and sixth year – at my high school. One of the perks of this was that the senior pupils had their own common room in the school basement, with a record player and loudspeakers. For a few, ear-bleeding months, Blizzard of Ozz and Heaven and Hell were never off that record player.

Mr Crowley (from Blizzard of Ozz)

I don’t think Ozzy had acquired the moniker the ‘Prince of Darkness’ yet. However, aware that darkness was part of his schtick, he included this song on Blizzard of Ozz – a paeon to the English occultist Aleister Crowley. Depending on your point of view, Crowley was truly the Wickedest Man Alive or was a piss-taking libertine who enjoyed terrorising genteel, respectable British society with exaggerated tales of his diabolism. The song is launched in melodramatic fashion by the organ-tones of keyboardist Don Airey, but Ozzy sings it with agreeable wistfulness: “Your lifestyle to me seemed so tragic with the thrill of it all. You fooled all the people with magic. Yeah, you waited on Satan’s call…”

For a really over-the-top version of Mr Crowley, check out this effort by Cradle of Filth.

Thereafter, Ozzy would put out a dozen more solo albums. The best that can be said about them is that they’re variable in quality. But their highlights are certainly better than anything on the seven albums Black Sabbath released during the same period that had neither Ozzy nor Ronnie James Dio singing on them.

And obviously… Paranoid (from Paranoid)

Yes, I’m glad this was what Ozzy sang at the very end of his farewell concert earlier this month. There was no better way to bow out.

© Vertigo