A few weeks have now passed since Colombo, the city where I live, emerged from Covid-19 lockdown.

Even now, walking about the city has a slightly eerie feeling of unreality. The traffic isn’t quite as heavy as it was, though it’s gradually returning to the standards of the congested bad old days. But some business premises remain closed, fewer pedestrians are using the pavements and nearly everyone is wearing a mask.

Not that I’m complaining about the masks, of course. When it comes to the wearing of these, I’m in agreement with Arnold Schwarzenegger, who memorably tweeted the other day, “The science is unanimous – if we all wear masks, we slow down the spread and can open safely. It’s not a political issue. Anyone making it a political issue is an absolute moron…” That sounds even better if you read it aloud in the Terminator’s accent.

I say ‘lockdown’, but in fact what we had for nearly two months in Colombo was a curfew, where you stayed indoors and supposedly weren’t even allowed to nip outside for a spot of exercise. Hence, whenever I went down to the front door of our apartment building to pick up a delivery, I’d be greeted by the sight of our neighbour from upstairs burning off calories by riding her bicycle around and around the building’s small concourse. Sri Lankan people seemed generally to accept and put up with the inconvenience of this. I suppose it’s partly due to unhappy past experiences. Events like the 30-year civil war, the 2004 tsunami and the Easter Sunday bombings last year have made them appreciate the importance and necessity of emergency security measures.

The curfew was imposed on Friday, March 20th. There was an experimental half-day lifting of the curfew four days later, which gave folk a chance to get to the shops and stock up on supplies. (By this point, Colombo’s food retailers hadn’t yet set up a coherent online system whereby people could order things from their homes and have them delivered.)

On March 24th, curfew-lifting day, I got up and headed out at about 7.00 AM, my goal being do some shopping at the nearest supermarket, Food City on Marine Drive. When I arrived at Food City, I discovered that a queue had formed outside, which was slowly being threaded into the premises by a group of shopworkers and policemen. I walked alongside that queue for the whole of the next block, counting the people as I went. The queue actually turned 90 degrees at the far corner of that block and continued up a side street, and by the time I reached the end of the queue I’d counted 173 people. Everyone was trying to ‘socially distance’ themselves from one another by keeping a metre of space between them, so it was a long queue of 173.

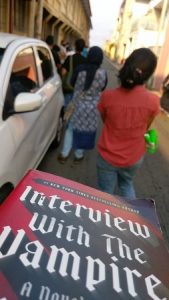

The queue inched along and more than two hours passed before I got into the supermarket. The shopworkers and police at the entrance were making sure that only a couple of dozen people were inside the shop at any one time, to enable social distancing. But I’d expected a long wait and brought a book along and I spent those hours in the queue reading. In fact, a long, grindingly slow queue was probably the best context in which to read this book, for it was Anne Rice’s 1975 gothic opus Interview with a Vampire. Yes, when you’re queuing for food in the middle of a pandemic, even Ms Rice’s florid and overwrought prose seems pretty bearable.

The people I saw outside and inside Food City behaved responsibly, but March 24th’s curfew-lifting didn’t seem to be a success. Later that day, I saw reports in the media about crowded shops, markets and vehicles across the city and the country where the infectious and opportunistic Covid-19 virus would have enjoyed a field day. Afterwards, when the authorities re-imposed the curfew, they kept it in place for a long, long time.

In fact, the only time I ventured beyond the edges of our premises during the next seven weeks was one day when I realised that I needed to get cash. By now Colombo’s retailers had managed to set up a working delivery system, but not everything could be paid for online and / or with cards. Sometimes you needed to pay the deliverers with physical money when they arrived at your door. So off I trudged to the nearest ATM, not knowing what to expect.

This experience did make me feel like I was journeying through a city in the grip of a pandemic – a pandemic portrayed in an apocalyptic sci-fi / horror movie. Traffic on Marine Drive was no more than a trickle. The only people I saw who weren’t in vehicles or uniform were the staff at the Lanka Filling Station – a few vehicles were nosing onto their concourse to get petrol – and a couple of guys on the far side of the road, next to the sea, loading white Styrofoam boxes of fish onto the back of a delivery truck. All the businesses along the road looked like they’d been shut for an eternity. Oddest of all was the sight of our local branch of the KFC, which I’ve rarely seen not busy. There was something utterly grim about the sight of all its chairs upturned and set on top of its tables, their jutting chair-legs forming a prickly metallic forest in the shadowy, unlit eating area.

Despite its close proximity to our building, the ATM I was heading for was actually in a different district of Colombo, across the Kirillapone Canal that forms the boundary between Wellawatta and Bambalapitiya. And a security checkpoint staffed by three armed soldiers and ten police officers and consisting of a tent, desk and wheeled metal barriers had been set up by the canal bridge. I noticed how this had also become the gathering point for the local population of crows, who usually assemble hungrily and hopefully where human beings assemble too. So I had to traverse this checkpoint, show them my passport and explain where I was coming from, where I was going to and why. I was allowed to continue to the ATM on the strict proviso that I returned home immediately afterwards.

During April and into May rumours about when the curfew would be lifted were plentiful, but it wasn’t until the week beginning May 11th that a modicum of normalcy returned in Colombo. Not only were businesses allowed to have some ‘essential’ employees back at their workplaces (as opposed to ‘working from home’), but the general public were permitted outside on one weekday according to the final digit of their ID card number. If that last digit on your ID card (or, if you were a foreign resident, your passport) was a 1 or 2, you were allowed out on Monday; if it was a 3 or 4, you were allowed out on Tuesday; and so on. For me, this meant I could finally escape house arrest on Thursday, May 14th.

I was actually working from home for most of that day, so I didn’t get to venture out until late in the afternoon, which in the pre-Covid-19 era would have coincided with Colombo’s homeward-heading rush-hour. This time the experience felt nowhere near as desolate as when I’d trudged to the ATM the previous month. Most of the city remained closed, however, and considering what time of day it was, the lack of traffic on Marine Drive was astounding. I was also shocked when a train rolled past along the nearby coastal railway tracks. In the normal world, the train would have been stuffed with end-of-the-day commuters. The more adventurous ones would be hanging out of the doorways while Colombo whooshed past below them. But some carriages in this train barely contained a soul.

I felt melancholy walking around Colombo that day because I passed a few businesses to which I’d given my custom in the past – okay, pubs – and they looked practically derelict. I wondered if they’d ever reopen. One example was the Western Hotel, which’d optimistically put potted palm trees out along its façade shortly before the virus and curfew arrived. Another was that mainstay of Sea Avenue, the Vespa Sports Club, its colonial-era bungalow standing silently in the middle of its empty courtyard.

More encouragingly, I happened to pass my favourite Chinese restaurant, the Min Han on Deanstone Place, just as one of its owners, Mo, materialised at its doorway. So I was able to enjoy a socially distanced blether with him. He told me that the restaurant was taking orders and providing takeaways and money was thankfully starting to trickle in again.

Now, a month later, the Min Han seems to be fully back in business and I’d advise all Colombo-based lovers of authentic Chinese food to head there immediately. It’s highly recommended.

One other feature of traversing this strange, semi-deserted version of Colombo was how, in places I’d walked through practically every day of the past six years, I noticed things in the quietude that I’d never noticed before. For example, there was a flowery Christian shrine near the Seylan Bank on Duplication Road. Or a depiction of Mariah Carey, lurking sinisterly in the undergrowth near the entrance of the disused Indra Regent building, a little further south along the same street.

So those are my memories of locked-down Colombo between March and May 2020. It was an economically brutal experience for the city and for the country as a whole. But I think it was a necessary experience because three months after Covid-19 appeared here, the total number of cases have been kept below 2000 and there’ve been only 11 deaths. Compare that with the shambles of a response to the crisis that went on in the UK, mis-orchestrated by bumbler-in-chief Boris Johnson. Or worse, what happened in the USA with Donald ‘Drink Bleach’ Trump at the helm. Let’s just hope that, after all the sacrifices made, and with life making a hopeful return to normal, Sri Lanka doesn’t have to deal with a resurgence of that bloody microbe in the near future.