© Bloomsbury

I first came across the works of Alan Moore in the mid-1980s, while I was a student in Aberdeen. One day, I discovered a ramshackle shop on the city’s King Street selling tatty second-hand paperbacks and comics out of cardboard boxes at ridiculously low prices.

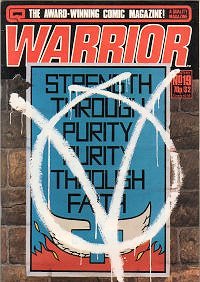

There, I managed to buy most of the 26 issues of a comics anthology called Warrior, which had appeared monthly from 1982 to 1985. Initially, I was attracted to Warrior because its contents included the continuing adventures of Father Shandor, a comic-strip character I’d been obsessed with in my early teens. (Shandor was a 19th-century Transylvanian monk who fought vampires and demons. He’d actually started as a movie character, played by the gruff, no-nonsense Scottish actor Andrew Keir, who was the foe of Christopher Lee’s Dracula in the 1966 Hammer horror movie Dracula: Prince of Darkness. He became the hero of a comic strip in the late-1970s magazine House of Hammer, whose editor Dez Skinn would later edit Warrior. At an even younger age, I’d been a big fan of Marvel Comics’ Doctor Strange and Shandor seemed a darker, more serious and more violent version of that.) However, it was only one of many serials in Warrior and the most striking of these sprang from the pen of Alan Moore.

These included Marvelman, a revival of a British superhero who’d originally been the lead character in a comic book that’d run from 1953 to 1964, and The Bojeffries Saga, about a family of Munsters-like misfits and monsters living in a council house in Northampton, which incidentally is Moore’s hometown. But it was the dystopian V for Vendetta, penned by Moore and drawn by David Lloyd (with occasional contributions from Tony Weare) that made me re-evaluate what comics were capable of doing.

Set in a neutral Britain that’s managed to avoid destruction in a nuclear war but now, in a dire situation after the subsequent nuclear winter, is under the heel of a fascist, totalitarian government, V for Vendetta was the first comic-book serial I’d encountered that seemed both utterly serious and utterly adult. Yes, this was a time when it was still assumed anything drawn as a series of cartoons, in a series of boxes, with speech bubbles, could never be adult and must always be juvenile. It also made uncomfortable reading – again, ‘uncomfortable’ was an adjective I hadn’t previously associated with comics – because (a) it was inviting its readers to associate with a hero who was, ostensibly, a terrorist, and (2) the authoritarian society depicted in V for Vendetta didn’t seem that far down the road from the one a certain Margaret Thatcher was engineering in Britain in the time.

Ironically, if the world of V for Vendetta was to come about, Thatcher wouldn’t have been in power for most of the 1980s. Presumably the story had been conceived before the 1982 Falklands War, which gave a massive boost to Thatcher’s popularity. Back then, it’d looked possible she’d lose the next British general election and the Labour Party, led by the pacifistic Michael Foot, could win it, which would have set up V for Vendetta’s neutral-Britain-survives-a-nuclear-war scenario.

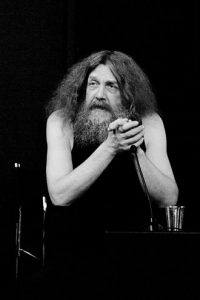

Anyway, 40 years later, it’s highly unlikely anyone would only find out who Alan Moore is after rooting around in a box of second-hand comics in a shop in Aberdeen. After V for Vendetta (published in its entirety by DC Comics’ Vertigo imprint in 1988-89), The Ballad of Halo Jones (1984-86), Watchmen (1986-87), From Hell (1989-98) and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (1999-2019), and his acclaimed work with established comic-book characters like Batman, Superman and Swamp Thing, and his authorship of the tomes Jerusalem (2016) and The Great When: A Long London Novel (2024), and his reputation as a magician and occultist, and his popularity as an interviewee and a social commentator, and his being garlanded with accolades such as ‘national treasure’, ‘sage’ and ‘world’s greatest living Englishman’, it’s fair to say we’re living in an era of Alan Moore ubiquity. And we’re all the better for it.

From wikipedia.org / © Quality Communications

Anyway, I’ve just read his 2022 collection of short stories, Illuminations. Of the nine pieces it contains, eight are good or great in my opinion. Also, one of the stories, What We Can Know About Thunderman, isn’t a short one but a 240-page novel. It’s about 30 pages longer than the other stories put together.

Fortunately, given its length, What We Can Know About Thunderman isn’t the story I consider to be a dud. No, I think the dud is the penultimate one, American Light – An Appreciation, which purports to a poem by an imaginary Beat poet called Harmon Belner, choc-a-bloc with references to the ‘San Franciscan and Beat culture’ and the ‘post-Beat counterculture that prevailed in San Francisco during the 1960s and 1970s’, plus an introduction and copious footnotes by an imaginary scholar called C.F. Bird. Connoisseurs of all things Beat may find it a delightful pastiche, snapshot and celebration of the movement, but it simply didn’t appeal to me, someone who finds most Beat writers tedious, pretentious and arsehole-y. (How I cheered when I read what Keith Richards said of Allen Ginsberg in the former’s autobiography: “…Ginsberg was staying at Mick’s place in London once, and I spent an evening listening to the old gasbag pontificating on everything. It was the period when Ginsberg sat around playing a concertina badly and making ommm sounds, pretending he was oblivious to his socialite surroundings.”)

What We Can Know About Thunderman on the other hand is a fictionalized history of the American mainstream comic-book industry where the foundational superhero of that industry isn’t Superman but a Superman-like character called Thunderman. It’s also an indictment of the business, which has inflicted indignities and belittlements on numerous writers and artists, including Moore, over the decades. For instance, Moore is justifiably bitter about losing ownership of V for Vendetta and Watchmen to DC Comics. (When he made a guest appearance in a 2007 episode of The Simpsons, Milhouse Van Houten was shown making a grievous faux pas by asking Moore to autograph a DVD featuring the DC Comics characters, Watchmen Babies in V for Vacation.)

Although the characters in Thunderman have unfamiliar names, comics fans won’t have difficulty linking many of them to real-life publishers, editors, writers and artists. I’m not particularly knowledgeable, though even I recognized one Sam Blatz “…in his tilted hat, his jacket slung over one shoulder like Sinatra…” and wearing ‘snazzy sunglasses’. Blatz’s chief talent is for titling characters: “…at least Sam’s monsters looked great, drawn by Gold or Novak, so that all he had to do was think up whacky names…” Yes, Blatz is Moore’s sour reimagining of Marvel Comics’ head-honcho Stan Lee. That would make the artists ‘Gold’ and ‘Novak’ the more talented, but less financially rewarded, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. There has been writing online, some of it in great detail, about who the cast-members of Thunderman represent in the real comics world. If your expertise in the field is lacking, as mine is, it may be useful to have one of those online pieces handy, for consultation, while you read the story.

Thunderman is impressively bilious as it charts its characters’ progress during the 20th and early 21st centuries. They start as young, naïve comic-book enthusiasts, become comic-book creatives, and wind up as middle-aged predators or victims: variously corrupt, grasping, sociopathic, perverted, ridiculous, embittered or crushed. The story is told from a range of perspectives and in a range of styles and formats, including interviews, monologues, reviews, playscripts, internet-forum discussions, psychoanalysis sessions and comic-book panels (described in written form), as well as in conventional prose. If not every part works equally well, the assorted viewpoints and formats keep it fresh. Fear not if something isn’t quite engaging you – something different will be along in another few pages.

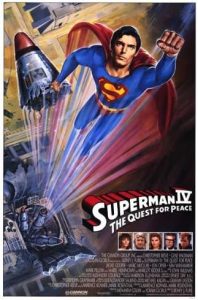

My favourite sections were the comic-book panels, which chronicle how the creators of Thunderman, Simon Schuman and David Kessler – thinly-veiled versions of Superman’s creators, Jerry Siegal and Joe Shuster – were conned out of the rights to the lucrative Thunderman franchise by American Comics, the story’s stand-in for DC Comics; and a series of reviews that evaluate how Thunderman has been adapted to the large and small screens. Again, Thunderman’s exploits in the cinema and on TV mirror Superman’s. I particularly enjoyed the review of Thunderman IV: The Search for Love, obviously inspired by 1987’s Superman IV: The Quest for Peace. However, while Superman IV had the late Chrisopher Reeve in the title role, trying to preserve his dignity in a poor film, Moore brilliantly imagines Thunderman IV featuring Robin Askwith, star of those dire British 1970s sex-comedies, the Confessions films: “…most of the supposed humour rests in the mullet-styled hero using his Thundervision to see through the walls of ladies’ changing rooms, complete with BOI-OI-OING sound effects.”

© Canon Group, Inc. / Warner Bros.

Elsewhere in Illuminations, Moore stretches his imagination and writing abilities with The Improbably Complex High-Energy State. This is both a cautionary tale and a riff on the paradox put forward by 19th-century physicist Ludwig Boltzmann, who mused that it was statistically more likely for a self-aware brain, perceiving an infinite universe, to come into being through random fluctuations of particles than it was for an infinite universe itself, as postulated under conventional cosmological theory, to exist. In other words, we’re more likely spontaneously-created entities thinking we see an infinite universe than we’re actual parts of an infinite universe. Moore’s story has such a brain – and a lot of other stuff – appearing soon after the universe does. As it becomes aware of its unique situation, it rapidly develops human, and depressingly familiar, personality traits.

From the birth of the universe in The Improbably Complex High-Energy State, Moore moves to the end of the world in Location, Location, Location. He describes the apocalypse in majestically vivid Book-of-Revelation fashion, but sets the action in the unassuming English market-town of Bedford. This is where the real-life Panacea Society, believers in the teachings of the 19th-century prophetess Joanna Southcott, believed the site of the original Garden of Eden to be. They also maintained a house on Bedford’s Albany Road as a residence for the Messiah to move into after the Second Coming. In Location, Location, Location, it transpires that, yes, the Panacea Society got it right and Jesus Christ – who’s presented like a well-meaning but slightly embarrassing ‘cool dad’, with a pierced ear and a T-shirt saying ‘I may be old, but at least I got to see all the best bands’ – has just arrived in Bedford to claim the house. The story is told through the eyes of an understandably distracted solicitor called Angie, who’s been given the task of overseeing the handover. This she has to do while images of giant winged beasts with lions’ heads and battling squadrons of angels fill the sky above. Location, Location, Location is an excellent example of Moore’s ability to combine the jaw-droppingly fantastical with the humdrum and mundane.

But the stories I enjoyed most in Illuminations were a trio of tales that struck me as belonging to a school of spooky British fiction that stretches from Arthur Machen, via Robert Aickman, to Ramsey Campbell, in that they present the supernatural in very British settings: everyday, awkward, slightly rundown and tawdry. Not Even Legend features an organization of hapless paranormal investigators called CSICON (the Committee For Surrealist Investigation of Claims Of the Normal), who are trying to get to grips with some cryptid-type beings so adept at hiding themselves that no one, until now, suspects they even exist. Not Even Legend has a complicated structure that rewards the reader’s patience when it becomes clear how clever the story’s premise is. And Moore’s enthusiasm for inventing strange new types of monsters is endearing. He mentions such creatures as Snapjackets, Mormoleens, Jilkies and – most prominently – Whispering Petes.

More conventional is Cold Reading about a phony, but pathetically self-justifying, clairvoyant who spots an opportunity to make easy money when a man asks him if he can contact the spirit of his deceased twin brother. A twist can be seen coming, but the story’s mixture of cynicism and melancholia, and its evocation of a bleak wintry night in Northampton, make it very atmospheric. Finally, I greatly enjoyed the title story, which takes place in a dilapidated, seen-better-days British seaside resort. Moore obviously relishes describing the setting. The tale of a middle-aged man returning to the coastal town in which, during his childhood, he used to holiday with his parents, it reminds me slightly of the Harlan Ellison short story One Life, Furnished in Early Poverty (1970). And there’s something about it that calls to mind the Gerald Kersh story The Brighton Monster (1948) too.

Your enjoyment of Illuminations may depend on your willingness to spend half of it reading a novel that’s a diatribe against the American comic-book industry. I was happy to do so, and I got a lot out of that story and out of the collection generally. Illuminations really did light up my reading life for a few days.

From wikipedia.org / © Matt Biddulph