© Franco London Films / ZDF Television

What a melancholy coincidence… A few weeks ago, for the first time in years, something got me thinking about the 1960s children’s TV show The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe and I watched part of an episode of it on YouTube. I wondered if its star, the Austrian actor Robert Hoffman, was still on the go, googled him and was pleased to find that he was. Then, the other day, I read on social media that Hoffman had just passed away.

Anyway, here’s something I originally posted in 2012, which mentions Hoffman and The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. It’s now been updated for 2022.

Politics, the economy and, indeed, cultural attitudes in Britain in the last half-dozen years have been dominated by Brexit. This, depending on your point-of-view, has either been a joyous and much-needed liberation of Britain from the stifling bureaucracy and political interference it’d had to put up while it was a member of the European Union; or the most disastrous decision Britain has made since the 1956 Suez Crisis, one that’ll doom the country to being a parochial, xenophobic wee dump that backpedals towards the 1950s while the other European nations get on with living in the 21st century. Anyone who regularly reads this blog will know which view I subscribe to. Namely, that if you believe there’s anything positive about Brexit, you must have one of those heads that proverbially ‘zip up the back’.

The Brexit vote in 2016 came 43 years after Britain joined the European Union, or the European Economic Community (EEC) as it was then. However, it’d be wrong to believe before 1973 Britons were wholly detached from the culture of continental Europe. Indeed, though I was a mere mite before 1973, much of my headspace had already been colonised by the continent. This was thanks to children’s television.

In the early 1970s, the BBC felt obliged not only to entertain kids after they’d arrived home from school and broadcast juvenile programmes from 4.00 to 5.45 PM, but also to broadcast such programmes during the mornings of school-holiday periods. The morning schedules of the summer holidays in particular were a challenge for the BBC to fill with kiddie-related material. As a result, the channel had to regularly raid its archives for old, dubbed children’s shows from France, Germany and elsewhere and broadcast those.

Let’s begin with my least favourite show. Growing up on a Northern Irish farm where there weren’t many neighbours to mix with, I depended for company during the summer holidays on the elderly couple who lived a few hundred yards along the road from our farmhouse. More precisely, I depended on their two granddaughters, who were around my age and usually came to spend much of the summer with them. Luckily for me, the neighbours’ granddaughters were a pair of Tomboys who were dependable for games of cops and robbers, cowboys and Indians, and other activities normally more associated with young males. However, they had one weakness, a fondness for a show called White Horses.

This was a co-production between German and Yugoslavian TV that’d been made back in 1965 but that rarely seemed to be off the BBC’s children’s holiday schedules in the early-to-mid-1970s. It followed the adventures of a girl from Belgrade, Julia, who was staying on her uncle’s horse ranch. Populating the ranch were handsome white steeds that made my two female playmates swoon with adoration.

As a boy, and not a fan of horses (white or otherwise), I thought this was the dumbest programme ever. And it constantly annoyed me that on those summer mornings the games of cops and robbers and cowboys and Indians would abruptly stop and my two playmates would run indoors to sit goggle-eyed in front of their television the moment White Horses came on. I have to say, though, that while I generally remember other kids’ TV programmes from then but not the details of individual episodes, two episodes of White Horses remain etched on my mind.

In one episode Julia found a metallic, saucer-shaped object on the grounds of the ranch and carried it to her uncle, who immediately screamed, “It’s a mine!” and flung it away as far as he could. At which point it exploded. In the other episode, the ranch’s dog was seen frothing at the mouth and in the ensuing pandemonium all the ranch-hands tore around on horseback, trying to hunt the rabid beast down. Come to think of it, for a silly girls’ show, White Horses was actually quite dark. It left me with the conviction that the European continent was a real danger zone, riddled with unexploded World War II landmines and overrun with rabid mammals. That’s a message I’m sure Brexiters like Nigel Farage and Jacob Rees-Mogg would approve of.

© Philips

One thing that really annoyed me about White Horses was the sickly theme song. This wasn’t a feature of the original German-Yugoslavian show but had been recorded by the Dublin singer Jackie Lee and stuck onto the dubbed BBC version. The lyrics went: “On my horses let me ride away, to my world of dreams so far away, let me run, to the sun, to a world my heart can understand, it’s a gentle warm and wonderland, faraway, stars away, where the clouds are made of candyfloss, as the day is born, when the stars are gone, we’ll race to meet the dawn…” Despite my intense dislike for it, however, the song is now regarded as a kitsch classic and has been covered many times, usually by ‘knowing’ indie-pop bands like Kitchens of Distinction and the Trashcan Sinatras. Even Catatonia’s Cerys Matthews has had a go at singing it. Here, if you can stomach it, is the original version.

Now if you wanted a Euro-kids’ TV show with a seriously bad-ass theme song, you didn’t have to look any further than The Flashing Blade, a historical swashbuckler made by France’s Office de Radiodiffusion Television Francaise (ORTF) in 1967. Set in the early 17th century, during the War of Mantuan Succession between France and Spain, the show’s theme song was accompanied by footage at the start of each episode showing the principals racing manically across countryside on horseback. Their manic-ness, of course, was increased by the fact that the film was wildly speeded up. The singer implored: “You’ve got to fight for what you want, and all that you believe, it’s right to fight for what we want, to live the way we please, as long as we have done our best, then no one can do more, and life and love and happiness, are well worth fighting for.” Here’s the show’s blood-stirring opening on YouTube.

Unlike White Horses, I don’t remember much about the story of The Flashing Blade, except that to my impressionable young mind it was very like The Three Musketeers. For some reason, however, I’ve never forgotten a scene where two characters – one presumably villainous because he sported a pointed beard – were playing chess and the villain made a comment about the uselessness of pawns with regard to the outcome of the game. The other player immediately came back with an observation along the lines of: “Even the smallest pebble can shatter the most beautiful of mirrors.” As a seven-year-old, this seemed the profoundest thing I’d ever heard.

© Office de Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française

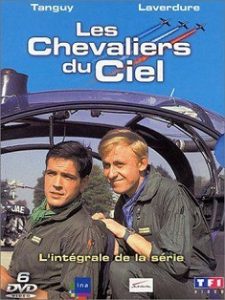

Also originating with France’s ORTF in 1967 was Les Chevaliers du Ciel, which ran on Gallic television for the next three years. By the time it turned up in anglicised form on British TV it’d been retitled The Aeronauts and given a new, hard-rockin’, by BBC standards, English-language theme song by the Canadian musician and TV presenter Rick Jones. His Aeronauts song went: “Better than best, boys, we pass every test, you’re ahead of the rest, when those crime-fighting Aeronauts are cutting those bounds, in a fury of sound, you’re a loser all round, against the crook-catching Aeronauts, so play in the wind, boys, you better give in, because your troubles begin when those two daring aeronauts fly!“ I can’t find the opening sequence for this one, only the song itself.

Incidentally, the memorably bearded, balding and intense-looking Rick Jones was no stranger to children’s TV programmes, as in 1972 he hosted Fingerbobs, which must’ve featured the cheapest and most low-fi puppets in the history of television. Over seven years he also worked on the BBC’s long-running show for pre-school kids, Play School (1964-88), a stint that ended when, to quote his Wikipedia entry, he was ‘fired by the BBC, after a fan sent him two cannabis spliffs at the corporation’s address’. Jones, alas, died in San Francisco last year.

Once again, though I remember the theme music well, I can’t recall much of what went on in The Aeronauts. Maybe that was just as well, since the show was about two hunky young guys called Ernest and Michel who were pilots in the French Air Force. As such, they might’ve spent the episodes bombing la merde out of insurgents in North Africa or Greenpeace activists in the South Pacific.

© Office de Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française

I’ve spoken ironically about the music on The Flashing Blade and The Aeronauts, but there’s no disputing the fact that the theme tune of Belle and Sebastian had a genuine haunting quality. This was the Anglicised version of Belle et Sebastien, which ran on French television from 1965 to 1970 and was based on the novel by Cecile Aubrey about a boy and his big Pyrenean mountain dog. It’s fitting that wistful Glaswegian indie-pop band Belle & Sebastian took their name from this show. And apparently its theme song was covered by New Zealand singer-songwriter Bic Runga a few years ago. Here’s the original version.

There are a number of things I remember about Belle and Sebastian, apart from its music and its obvious star, the hefty canine Belle. I remember being awed by the sheer, bleak mountain landscapes that formed its backdrop – it’d been filmed around the village of Belvedere in the Alpes-Maritimes. Indeed, years later, when I finally saw the Alps for real, the first association I made in my head was with that old French kids’ TV show.

I also remember how the voices in Belle and Sebastian puzzled me. Not being aware of dubbing procedures or the fact that the BBC employed a small group of actors to do the English dialogue for these imported shows, I couldn’t figure out at the time why the adults in Belle and Sebastian sounded exactly like the adults in White Horses. By the way, Sebastian in the show was played by Mehdi el Glaoui, who was Cecile Audrey’s son. Little Mehdi’s father was Moroccan and indeed his grandfather had been the Pasha of Marrakech.

© Office de Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française

However, musically, the best Euro-kids’ programme of all was surely The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. Robinson Crusoe was of course a British cultural property, but this children’s drama version of the story had been made in 1964 by France’s Franco London Films (FLF) and starred Austrian actor Robert Hoffman in the title role. The BBC got its hands on it, dubbed it and broadcast it regularly during its children’s TV schedules from the mid-1960s to the late 1970s.

The BBC added a lovely, mock-classical score composed by Robert Mellin and P. Reverberi, which managed to be both stirring and slightly desolate. I’ve read somewhere that the spiralling opening chords were meant to represent the breakers striking the beach of Crusoe’s desert island. It doesn’t surprise me that when electronica band The Orbital put together 19 of their favourite tracks in 2002 for the Back to Mine compilation series, they decided to close their compilation with this tune.

To be fair to The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, a lot more of the show has remained with me over the years than just its theme music. For a long time, Hoffman’s youthful features formed my image of how the character should look – so that when I saw other versions of the story later on, such as a 1974 BBC adaptation with Stanley Baker and a more politically correct movie adaptation called Man Friday (1975) with Peter O’Toole and Richard Roundtree, I couldn’t accept them. The series took liberties with Daniel Dafoe’s novel, though. For example, it climaxed with a shipload of pirates invading Crusoe’s island. At which point, Man Friday took off and hid in the island’s jungle, and started killing the pirates off one by one.

Finally, for pure weirdness, you couldn’t beat The Singing Ringing Tree, which had started life as a film made by an East German studio, Das Singende Klingende Baumchen. The BBC duly chopped it into TV-serial form. Even by the standards of the other Euro-kids’ shows I saw at the time, The Singing Ringing Tree was particularly venerable, dating back to 1957. It lingers in my mind because, although it was ostensibly a fairy tale, it spooked the hell out of me.

© Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft

With characters including an evil dwarf, a humanoid bear creature (who was actually a prince transformed by a magic spell) and a gigantic goldfish, the series resembled a Brothers Grimm story directed by David Lynch. Reviewers, at least those who took the show seriously, noted an influence of German expressionism on how it looked and an influence of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) in particular. To my seven-year-old sensibilities, the fate suffered by the dwarf at the end was especially traumatising. He was last seen swooping around in the air and then plunging through the thin-crusted ground and vanishing in a belch of volcanic, sulphurous smoke.

If this makes me sound wimpish, I should point out that I wasn’t alone in being scared by the show. The comedian and impersonator Paul Whitehouse said of The Singing Ringing Tree that it used to make him ‘pee his pants’ when he was a kid. Perhaps as a way of exorcism, Whitehouse staged a spoof of it on his popular comedy programme The Fast Show (1994-97) called The Singing Ringing Binging Plinging Tinging Plinking Plonking Boinging Tree with, somewhat inevitably, the ubiquitous Warwick Davies in the role of the dwarf. And in 2006, the show lent its name to a ‘wind powered sound sculpture’ in the Pennines in Lancashire.

And there ends my round-up of kids’ Euro-telly. They might have been a set of old, cheap and badly-dubbed TV shows, but nonetheless they converted me into a good little European – even if at the time I still thought Brussels was something you were force-fed at Christmas, not the hub of one of the most important political and trading alliances in the world.

© Franco London Films / ZDF Television