© NLT Productions / Group W Films / United Artists

We’re now in December and, as usual, people are talking about what Christmas movies they’ll be watching on and around December 25th. So here’s a piece – originally posted on this blog back in 2017 – about my all-time favourite Christmas movie. It definitely qualifies as a Christmas movie since its events take place during the festive season and against a background of Christmas trees, decorations and carols. Though if you’re accustomed to the cosy festive cheer of It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) or The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992), you might not be ready for the squalor, drunkenness, brawling, vandalism, vomit, sweat-stains, flies, kangaroo-slaughter and Donald-Pleasence-going-bananas that constitute the Wake in Fright Christmas experience…

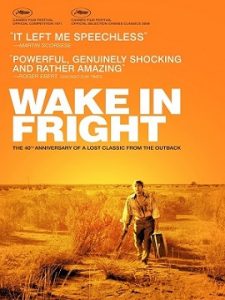

It took a while for the 1971 Australian epic Wake in Fright to win some respect, but it finally got there in the end. It flopped on its initial release, despite being nominated for the grand prize at that year’s Cannes Film Festival, and for a long time afterwards it only existed in heavily cut and low-quality versions. However, following restoration and remastering work during the noughties, a new version of Wake in Fright was shown at Cannes in 2009 and now, belatedly, the film is seen as an important precursor to the New Wave of Australian Cinema that produced the likes of The Cars That Ate Paris (1974), Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978), Mad Max (1979), My Brilliant Career (1979) and Breaker Morant (1980).

Directed by Ted Kotcheff, Wake in Fright tells the story of John Grant (Gary Bond), a young Australian schoolteacher beset by frustration and a sense of injustice. He dreams of moving to England, something that many young Australians were doing in real life at the time, most famously Barry Humphries, Clive James, Germaine Greer and Robert Hughes. There, he muses, he’ll become ‘a journalist’. It has to be said that for someone wanting to write as a career, he spends suspiciously little of the film, none of it in fact, doing any writing.

For now, though, John’s stuck in a school in a tiny Outback settlement surrounded by vast expanses of nothingness. Kotcheff highlights this at the film’s start with a 360-degree panning shot that still looks mightily impressive today. John’s exile here shows no likelihood of ending soon, because to leave his job he needs to pay off a bond signed with the Australian government to cover the costs of his teacher-training.

© NLT Productions / Group W Films / United Artists

Wake in Fright begins with John finishing his final lesson before the Christmas vacation and taking a train to a mining town called Bundanyabba, where he plans to catch a plane to Sydney for a few weeks in the company of his glamorous city-based girlfriend. But his plans go askew when he arrives in Bundanyabba, ‘the Yabba’ as it’s known to its inhabitants, and he spends a night there before the plane flies. In succession, John enters a drinking establishment that isn’t so much a pub as a pumping station, supplying the Yabba’s thirsty male citizens with industrial volumes of beer; befriends a hulking policeman called Jock Crawford (Chips Rafferty), who takes him to a late-night eatery; discovers a gambling den at the back of the eatery where money is bet, won and lost on the tossing of pairs of coins; gets involved in a game; impulsively bets everything he has in the hope of winning enough to pay off his bond; and loses everything. Thus, the next day, John wakes up penniless, unable to pay for his flight and marooned in the Yabba.

By this time, he’s also met local eccentric ‘Doc’ Tydon, who’s played by none other than the great English actor Donald Pleasence. When you see the crazed, drunken Pleasence tossing the pair of coins on which John’s fortunes depend, you know it’s going to end badly.

After losing all his money, John, who was initially disdainful of the macho, swaggering, hard-drinking, hard-gambling mindset that possesses most of the Yabba’s male inhabitants, gradually sinks to the point where the same mindset possesses him. He’s befriended by a well-to-do man called Tim Hynes (Al Thomas) who brings him home and introduces him to his daughter Janette (Sylvia Kay). Hynes, obviously seen as a soft touch by his Yabba neighbours, soon has a crowd in his living room drinking his beer and leering after Janette, including the ubiquitous Doc Tydon and a pair of young bogans called Joe (Peter Whittle) and Dick (future Australian movie star Jack Thompson).

© NLT Productions / Group W Films / United Artists

After a severe all-night drinking session, John, now stained, grubby and worse-for-wear, comes to in Tydon’s shack. This is a hellhole with kangaroo meat heaped in greasy pans and clusters of dead flies stuck to dangling flypaper strips. We don’t get to see the outdoor toilet – the Donald Pleasence dunny – but from what we hear it’s even more hideous than the shack. It transpires that John drunkenly arranged to go on a kangaroo shoot with Joe and Dick, who soon show up at the shack in a vehicle loaded with guns and booze. All four head into the Outback to hunt ’roo and what follows is Wake in Fright’s most notorious sequence, wherein the quartet blast away a pack of kangaroos and wrestle with and stab to death the wounded ones. Such is the carnage that even in 2009, during the film’s re-screening in Cannes, a dozen people walked out of it.

Now completely deranged, John included, they wreck an Outback pub on their way home. The next day, after waking up in Tydon’s shack in an even worse condition, John manages to stagger off. Appalled by his own degradation, he attempts to hitchhike out of the Yabba and the whole way to Sydney, but again things don’t go according to plan. Finally, despairing and practically psychotic, John hits on another way of escaping from the Yabba, the most drastic way possible…

It’s easy to see why, when Wake in Fright was released in 1971, Australian audiences stayed away in droves. With its scenes of heavy-duty and illicit drinking (“Close the door, mate,” someone shouts when John walks into a pub and finds the entire male population of the Yabba boozing inside, “we’re closed!”) and incessant gambling (men standing robotically at rows of bar ‘pokies’ or acting as a baying mob in a backroom den), and with its depictions of violence, sexism and general macho bullshit, it doesn’t portray Australian culture of the time in a flattering light.

One scene sure to bait 1970s Australian viewers takes place in a pub. The boozers and gamblers suddenly fall silent, stand to attention and face an ANZAC memorial wall-mural while a radio announcer exhorts them to ‘remember the fallen’. When the silence ends a moment later, they dive back to their beer and slot machines.

© NLT Productions / Group W Films / United Artists

Then there’s the gruelling kangaroo shoot where bullets tear bloodily through what are clearly real animals. That must have traumatised international audiences whose images of Australia in 1971 probably mostly came from the popular, cuddly kids’ TV show Skippy the Bush Kangaroo (1968-70). A statement in the film’s end-credits assures us that the kangaroos weren’t slaughtered for the film. Rather, Kotcheff and his crew shadowed a group of professional ’roo hunters one night and filmed the shootings, which would have taken place whether Wake in Fright was made or not. Then this documentary footage was spliced into the film.

What the filmmakers did isn’t above criticism, though. It’s been pointed out that the powerful spotlight they used to film the hunt also enabled the hunters to blind and target their prey. Kotcheff later described the experience as a ‘nightmare’ because, as the night continued, the hunters became drunk, their shooting grew less accurate and kangaroos ended up horribly maimed. Things got so bad that the film crew pretended there’d been a power cut so that the spotlight no longer worked and the shooting had to stop. Most of the footage proved to be so upsetting that Kotcheff decided he couldn’t use it, though what is shown is bad enough.

The footage was also shown to the Royal Australian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty for Animals. They actually urged the filmmakers to include it in Wake in Fright, hoping it’d spark an outcry and help such madcap hunting to be banned.

Wake in Fright is a grim watch, then, but its cast is a pleasure. Gary Bond, with his finely sculpted features, blond hair and sonorous, cultivated voice, achieves a perfect balance between arrogance and vulnerability. He’s priggish but we still worry about him as his situation goes from bad to worse. Also effective are Chips Rafferty as the lugubrious policeman Crawford, who partakes of the roughneck culture around him without overdoing it and views John’s gradual succumbing to it with mixed disdain and concern; Al Thomas as Hynes, good-hearted but, wandering around the Yabba in a costume of fedora, shirt and bowtie, baggy shorts and knee-length white socks, sadly pathetic too; and Sylvia Kay as Hynes’s daughter Janette, whom John discovers is less repressed than she first appears.

© NLT Productions / Group W Films / United Artists

But the true star of Wake in Fright is Donald Pleasence. As Doc Tydon, he explains himself thus: “I’m a doctor of medicine and a tramp by temperament. I’m also an alcoholic. My disease prevented me from practising in Sydney but out here it’s scarcely noticeable. Certainly doesn’t stop people from coming to see me.” I wondered how convincingly the man who played Ernst Stavros Blofeld in You Only Live Twice (1967) would appear in the milieu of Wake in Fright but Pleasence nails it. He’s perfect whether he’s sober and observing icily how John flinched at the touch of Crawford’s ‘hairy hand’; or drinking beer whilst standing on his head to demonstrate how the oesophagus muscles are stronger than gravity; or slyly taunting John about the ‘open’ relationship he enjoys with Janette; or drunkenly raving on a pub-porch about ‘Socrates, affectability, progress’ being ‘vanities spawned by fear’ while Joe and Dick punch lumps out of each other behind him.

Wake in Fright could be dismissed as an expression of middle-class disdain for the lower-brow culture and less-mannered behaviour of the proletariat, but I feel that’s a misinterpretation. When John complains to Tydon about “the aggressive hospitality” of the Yabba, and “the arrogance of stupid people who insist you should be as stupid as they are,” Tydon retorts: “It’s death to farm out here. It’s worse than death in the mines. You want them to sing opera as well?” And when John slips down the slippery slope, a slope Tydon has already descended, it’s not because he’s had to become a brute to fight off other brutes around him (like in another 1971 movie, Straw Dogs). In John’s case, he’s entered an environment so harsh and thankless it can turn anyone into a brute.

It’s worth noting too that some people whom John encounters on his dark odyssey, like Crawford and Hynes, exhibit more kindness than he does himself. Even Tydon, who at times seems beyond all help, reveals some decency at the end.

Wake in Fright will celebrate its 50th anniversary next year, but it’s a film that hasn’t acquired any middle-aged flab or stodginess. It still seems as lean, mean, raw and unsettling as it did to audiences back in 1971. And it’s fitting that Nick Cave, the Victoria-born singer-songwriter and God-like genius whose work has frequently shared Wake in Fright’s bleak, brutal worldview, calls it ‘the best and most terrifying film about Australia in existence’.

© NLT Productions / Group W Films / United Artists