From Wikipedia / © Antonio Monda

May 19th saw the death of Martin Amis, reckoned by some to be the greatest British novelist of his generation. I have to say that’s not an opinion I shared, although I liked his 1984 novel Money and some of the stories in his 1987 collection Einstein’s Monsters. Anyway, one thing I noticed about the lengthy obituaries of Amis I read after his passing – none of them mentioned the fact that he wrote the script for 1980’s science-fiction movie Saturn 3. This features a saucy robot, programmed with the libido of Harvey Keitel, pursuing Farah Fawcett around a base on one of Saturn’s moons. Why the omission? No doubt Amis’s obituarists declined to mention it out of respect. Saturn 3 was an embarrassment and Amis surely left it off his CV.

However, Amis and Saturn 3 do highlight how, over the decades, well-respected authors have been involved with the film industry – a world less interested in creative endeavour and excellence and more interested in giving the public what it wants, putting bums on seats and making a fast buck – and the results have frequently not been pretty.

Here are a few of my favourite examples of novelists and filmmakers colliding and the movies birthed by those collisions being, let’s say, memorable for the wrong reasons.

© Amicus Productions

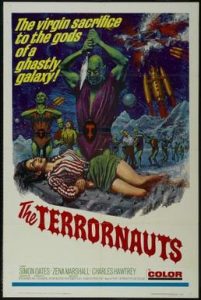

John Brunner and The Terrornauts (1967)

The science-fiction author John Brunner was highly regarded in his day and won both the Hugo and the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA) Awards for his 1968 novel Stand on Zanzibar. Also, his 1979 novel The Jagged Orbit netted another BSFA award and his pessimistic and prescient 1972 novel, The Sheep Look Up, about extreme pollution and environmental disaster, was much admired too. Though he’s not so well-remembered now, the BBC website did devote a feature to him in its Culture section a few years back.

Perplexingly, the only film script Brunner ever wrote was for the ultra-low-budget British sci-fi movie The Terrornauts (1967), which is about some astronomers contacting the remnants of an alien civilisation stowed away on an asteroid, being abducted and taken to that asteroid, and eventually having to fight off an invasion fleet that’s heading towards earth. Brunner’s script was based on a book called The Wailing Asteroid (1960) by another sci-fi writer, Murray Leinster. I saw The Terrornauts on late-night TV when I was 11 and even at that young age thought it was dreadful, with its poverty-row special effects, its cardboard sets, and the thuddingly incongruous presence of comedy actors Charles Hawtrey and Patricia Hayes, inserted into the proceedings for alleged ‘comic relief’. Still, The Terrornauts was so terrible that it burned itself into my memory and I’ve never been able to forget the bloody thing since. For the filmmakers, I guess that was some sort of achievement.

Chief among those filmmakers was producer Milton Subotsky, who ran Amicus Productions with Max J. Rosenberg during the 1960s and 1970s and was better known for making horror movies. I read an interview with Brunner once and he confessed to writing The Terrornauts as a favour to Subotsky, who was a friend of his. Subotsky and Rosenberg, incidentally, had form in getting literary folk to pen their screenplays. They drew at various times on Robert Bloch, Margaret Drabble, Harold Pinter and Clive James, the latter for a film that never got off the drawing board. And for their 1974 lost world / dinosaur epic The Land That Time Forgot, they hired another esteemed science-fiction writer, Michael Moorcock. The low-budget dinosaurs in The Land That Time Forgot are rubbery and a bit laughable by today’s standards, but Moorcock was gracious enough to describe the film as ‘a workmanlike piece of crap.’

And speaking of dinosaurs…

© Hammer Films

J.G. Ballard and When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1969)

Ballard is one of my all-time favourite writers. While a few filmmakers have come close to successfully translating his disturbing, dystopian and hallucinogenic literary visions into celluloid, such as David Cronenberg did with Crash (1996) and Ben Wheatley with High–Rise (2015), the pulpy When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth was, weirdly, the only film that Ballard himself scripted. This was a sequel by Hammer Films – like Subotsky and Rosenberg’s Amicus, a British company best known for making horror movies – to its 1965 epic One Million Years BC, featuring Raquel Welch as a fur-bikini-clad cavewoman and with splendid stop-motion-animation dinosaurs courtesy of special-effects genius Ray Harryhausen.

While One Million Years BC is a movie to watch and enjoy with your brain set at low gear, When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth is one where you need to switch your brain off altogether. Aside from the obvious scientific absurdity of human beings and dinosaurs being shown to exist at the same time, when they’d really missed each other by 65 million years, the film ends with a natural cataclysm so violent that part of the earth breaks off and creates the moon. But somehow, its main characters survive the carnage. The dinosaurs this time were animated by Jim Danforth and, though not up to Harryhausen’s standard, they’re good fun.

How, you wonder, did Ballard get emmeshed in such hokum? In his 2008 autobiography Miracles of Life, he gives an amusing account of meeting Hammer producers Aida Young and Tony Hinds when they were trying to brainstorm ideas for the film. The meeting had not gone well, but then Ballard rather desperately suggested that the big cataclysm at the end contain not a tidal wave crashing in, but one surging out from the shoreline. This would reveal “’…All those strange creatures and plants…’ I ended with a brief course in surrealist biology… There was silence as Hinds and Aida stared at each other. I assumed I was about to be shown the door… ‘When the wave goes out…’ Hinds stood up, clearly rejuvenated, standing behind his huge desk like Captain Ahab sighting the white whale. ‘Brilliant. Jim, who’s your agent?’”

© Rothernorth Films / Redemption Films

Fay Weldon and Killer’s Moon (1978)

Here’s the most mind-boggling collaboration on this list. On one hand, we have the feminist author Fay Weldon, who in works like The Life and Loves of a She-Devil (1983) strove to “write about and give a voice to women who are often overlooked or not featured in the media.” On the other, we have Alan Birkinshaw’s bonkers, grubby, low-budget horror effort Killer’s Moon, which seems the last thing Weldon would get involved with. Yet, uncredited, she rewrote the film’s dialogue.

Killer’s Moon has a quartet of escaped lunatics (wearing bowler hats like the Droogs in Stanley Kubrick’s controversial 1971 classic A Clockwork Orange) stalking the Lake District and terrorising some teenaged girls on a school trip whose coach has broken down. The loonies’ psychiatric treatment has included being dosed with LSD and now, mistakenly, they believe themselves to be dreaming. This makes them think they’re free to indulge without any repercussions in their darkest fantasies, which consist of rape, murder and animal mutilation. But don’t worry, animal-lovers. The dog that loses a limb early on, and spends the rest of the film hobbling about on three legs, was three-legged in real life. According to Killer’s Moon’s Wikipedia entry, she “was originally a pub dog who had lost a leg as the result of a shotgun wound sustained during an armed robbery. She was later awarded the doggy Victoria Cross award for bravery.”

Weldon’s involvement was for a familial reason. Director Birkinshaw was none other than her brother. She grumbled that by working on Killer’s Moon, she’d turned it into a ‘cult film’, but that’s exaggerating things a bit. Seen in 2023, Killer’s Moon is no cult film. It’s still daft, badly-made tat, and the bits of it that once seemed shocking just seem funny today.

© ITC Entertainment

Martin Amis and Saturn 3 (1980)

And now the movie that inspired this entry, the dire Saturn 3. Amis’s script was based on a story by John Barry – not the composer most famous for his work on the James Bond films, but John Barry the set designer on Star Wars (1977), who died of meningitis the year before Saturn 3 was released. Horror writer Stephen Gallagher was assigned the job of writing Saturn 3’s tie-in novelisation and once said of it: “The script was terrible. I thought it was bad then but in retrospect, and with experience, I can see how truly inept it was.” Gallagher added that this may not have been Amis’s fault and the script could have fallen victim to the film industry’s penchant for endless re-writing. He heard later that “every script-doctor in town had taken an uncredited swing at it, so it’s impossible to say if it was stillborn or had been gangbanged to death.”

Supposedly, Amis based some of his novel Money on his experiences with Saturn 3. It’s even said that one of Money’s characters, the ageing movie star Lorne Guyland, who’s convinced of his enduring youth and virility and isn’t afraid to disrobe and flaunt his body in an effort to prove it, was inspired by Saturn 3’s star Kirk Douglas. Years later, Amis remarked: “When actors get old they get obsessed with wanting to be nude… And Kirk wanted to be naked.”

© Zoetrope Studios / Golan-Globus

Norman Mailer and Tough Guys Don’t Dance (1987)

Three years after the publication of his crime-noir pastiche Tough Guys Don’t Dance, Norman Mailer got the chance to turn the book into a film starring Ryan O’Neal, Isabella Rossellini, Lawrence Tierney and Wings Hauser. The venerable American novelist was both co-scripter and director. I wrote extensively about Tough Guys Don’t Dance-the-movie a couple of months ago, so I won’t repeat here too much of what I said. It was, I wrote, “a delirious slice of so-bad-it’s-good campness”, where the cast visibly struggle “as they try to get their tongues, and their minds, around Mailer’s dialogue, which is largely fixated on performing the sex-deed with adequate levels of manliness. At one point Rossellini tells O’Neal that she and her husband, Hauser, ‘make out five times a night. That’s why I call him Mr Five.’ Though this is contradicted when Rossellini and Hauser have an argument. ‘I made you come 16 times – in a night.’ ‘And none of them was any good!’”

And of course, there’s the scene where hero Ryan O’Neal “finds out about his wife’s infidelity and reacts with a jaw-dropping display of bad acting – ‘Oh man! Oh God! Oh man! Oh God!’ – which, over the years, has become so infamous it’s now an Internet meme.”

© Scott Free Productions / 20th Century Fox

Cormac McCarthy and The Counselor (2013)

Also not having much success with sexy dialogue was legendary American author Cormac McCarthy, who wrote the script for the Ridley Scott-directed movie The Counselor. At one point in The Counselor, we get an auto-erotic scene – that’s ‘auto’ as in ‘involving automobiles’ – where Cameron Diaz makes out with Javier Bardem’s sports car. While grinding against the windscreen on her way to a climax, and flashing a certain part of her anatomy at Bardem on the other side of the glass, he likens the sight to “one of those catfish things, one of the bottom-feeders you see go up the side of the fish tank.”

Most critics panned The Counselor, presumably because they’d hoped that it would combine the intensity of McCarthy’s celebrated ultra-violent Western novel Blood Meridan (1985) with the intensity of Scott’s darkly-perverse space-horror movie Alien (1980). What they got, though, was a bewildering crime thriller about drug cartels that, to quote Mark Kermode in the Observer, “gets an A-list cast to recite B-movie dialogue with C-minus results.”

Michel Houellebecq and the KIRAC arthouse porn movie (2023)

Many writers have turned up in films as actors, usually in supporting or cameo roles – Maya Angelou, William S. Burroughs, Stephen King, Salman Rushdie and, indeed, Norman Mailer and Martin Amis (who as a blond 13-year-old starred in 1965’s A High Wind in Jamaica). I doubt, though, if any of these have generated as much noise as French author Michel Houellebecq’s recent, er, performance in a film production from radical Dutch art collective KIRAC (Keeping It Real Art Critics). I haven’t managed to find the title of the film — which sounds like it belongs to the ‘arthouse porn’ category — in the news reports about it.

Houellebecq, it transpires, agreed to be filmed having sex in the movie and signed a waiver saying that the only restriction on his participation was that his face and his ‘block and tackle’ didn’t appear together in the same shot. KIRAC didn’t even extend an invitation to him originally. It was Qianyun Lysis, Houellebecq’s better half, who suggested they use her husband – and no, it’s not her, but another woman who appears in bed with Houellebecq in the film. Now anyone who’s read his sex-filled and provocative novels, such as Atomised (1998) and Platform (2001), would assume this sort of thing is right up Houellebecq’s street. However, he lost his enthusiasm for the project after a few days of filming (and after the deed had been captured on camera). He then denounced the production and has since been trying, and failing, to stop KIRAC releasing the film in France and Netherlands.

If I was crass and prurient, I would roll my eyes at this and give a little cry of “Oh là là!” But I’m not. So, I won’t.

© From Wikipedia / © Fronteiras do Pensamento