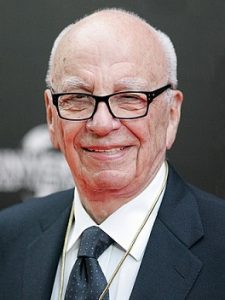

From wikipedia.org / © Eva Rinaldi

A while ago on this blog, I conducted the following thought-experiment. Imagine that current trends result in the world becoming a globally-warmed, war-ravaged hellhole inhabited by only a few surviving remnants of humanity. But those remnants somehow manage to lay their hands on a time machine and realise they can send an assassin back in time, in the manner of the James Cameron / Arnold Schwarzenegger movie The Terminator (1984). Who would they have their assassin target in, say, the late 20th century to change the course of history and prevent the world from turning into crap?

As I mused at the time, “The young Donald Trump? The young Vladimir Putin…? Neither. I suspect those guys would be considered small beer compared to the one the time-travelling assassin from the future would really go after… Rupert Murdoch.”

Wizened 92-year-old media mogul Murdoch was recently in the news because he announced his decision to step down as head of News Corp and the Fox Corporation in favour of his son Lachlan. Murdoch certainly looks his age, but it sometimes felt like he was going to live forever and keep running his media empire forever. Regular nocturnal blood-meals sucked from the throats of helpless victims are evidently good for the constitution. That said, lately, the old monster had begun to look a little vulnerable, both in his business dealings and in his personal life.

April this year saw his Fox News network fork out nearly 790 million dollars to settle a lawsuit brought against it by the voting-equipment company Dominion. This was after the network told outrageous porkies about the company switching votes in the 2020 US presidential election so that Donald Trump wouldn’t win it. Among the guff peddled by Fox was the claim that the company was owned by Venezuelans and had experience of swinging elections for the late Hugo Chavez.

Meanwhile, though old Rupe had once wooed the ladies with confident charm, like an extremely shrivelled George Clooney, he’s also looked less sure-footed on the romantic front recently. In 2022, he ended his fourth marriage, to Jerry Hall, by unchivalrously sending her an email to inform her that she’d been dumped. Hall was unsurprisingly miffed, as during the Covid-19 pandemic she’d gone out of her way to ensure her aged husband stayed isolated and avoided getting the virus, which for someone of his years would probably have been a death sentence. Earlier this year, he announced his engagement to former radio host Ann Lesley Smith, but this lasted just two weeks. That’s even shorter than a Liz Truss premiership. Apparently, Murdoch started to panic at Smith’s loopy evangelical-Christian pronouncements, which included the assertion that Tucker Carlson was ‘a messenger from God.’

But you can’t keep an old horn-dog down. Rupe is currently engaged again, this time to Elena Zhukova, who was once married to the Russian billionaire – don’t mention the ‘O’ word – Alexander Zhukova. At this rate, Murdoch will have got himself betrothed 16 more times before he reaches treble-figures.

© Prana Film / Film Arts Guild

Now that Murdoch has stepped back from the media-controlling activities that have kept him busy for the past 71 years, ever since the age of 21 when he inherited an Adelaide newspaper, the News, from his dad, what legacy does he leave? If he had a shred of conscience, morality and decency – which of course he doesn’t have, which makes this an academic statement – he’d surely howl in despair and incarcerate himself in a Trappist monastery for the rest of his days to do penance for his multiple sins. Or just top himself. Murdoch’s media operations have, over decades, caused massive harm to the well-being of humanity.

He pushed the rapacious neoliberal agenda of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, with its credo that greed is good, the market should be worshipped and the financial safety nets and infrastructure that held societies together, and looked after their most vulnerable members, weren’t worth bothering about. Thatcher said it all when she declared in 1987, “There is no such thing as society.” His outlets have gone to great lengths to ignore and discredit the overwhelming scientific evidence that manmade climate change is happening and poses a terrifying threat to our civilisation’s future. In Australia, a country that’s already baking and burning as the climate catastrophe unfolds, Murdoch newspapers like the Australian and Sydney’s Daily Telegraph cheer-led right-wing moon-howler Tony Abbott into power in 2013 – Abbott once dismissed climate change as ‘absolute crap’. And in the USA, Murdoch has used Fox News to build up a vast, paranoid, delusional, far-right-wing ecosystem whereby millions of gullible people now accept the lies of Donald Trump as gospel truth. Fox could very well see to it that Trump wins the presidency again in 2024. At which point, the world’s biggest superpower will make the transition into authoritarianism.

Murdoch is truly the man with the reverse-Midas touch. Everything he sticks his finger in turns into manure. Yet this never seems to stop him generating huge amounts of money, so he’s happy. No wonder his son James, that rare thing indeed, a Murdoch with a conscience, quit the board of News Corp in 2020, sickened by the horrors his old man had empowered.

In the UK, Murdoch has long exerted his toxic influence through the swathe of national newspapers he owns: the Times, Sunday Times, Financial Times, Sun and Sun on Sunday. His reign of terror began when he acquired the Sun in 1969. The history of that particular tabloid since then, when it hasn’t devoted itself to gleeful, lowest-common-denominator stupidity with headlines like ‘WEREWOLF SEIZED IN SOUTHEND’ and ‘FREDDIE STARR ATE MY HAMSTER’, has been an unrelenting saga of horribleness.

In the 1980s, when the Sun was under the stewardship of the repugnant Kelvin MacKenzie, it revelled in homophobia and gloated over the AIDS epidemic, which it dubbed the ‘gay plague’ and insinuated straight people had nothing to worry about. It catered for the ‘dirty mac’ brigade with its ‘page three’ girls, at least one of whom, Samantha Fox, was only 16 when it displayed her topless. And it lied through its teeth about the behaviour of Liverpool football fans at the 1988 Hillsborough Disaster, to cover up the failings of the police that day. That led an embargo of the Sun in Merseyside, which is still in force now. If only the British population generally treated the rag with the same contempt that the Scousers do. (I also admired the attitude of the late playwright Dennis Potter, whom the Sun dubbed ‘Old Flaky’ on account of his crippling psoriasis. When he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, he named his cancer ‘Rupert’.)

More recently, the Sun provided a platform for Katie Hopkins, someone even more repellent than MacKenzie, who likened migrants to ‘cockroaches’ and advocated the use of gunboats to stop them. And its incessant abuse of the European Union, European countries and European people (‘frogs’ and ‘krauts’ to a man and woman) climaxed with the newspaper’s enthusiastic support for Brexit – ‘BELEAVE IN BRITAIN’, its front page declared on the day of the referendum in 2016. It was no surprise that Murdoch welcomed Brexit, regardless of the economic, diplomatic and reputational damage it inflicted on the UK. He famously commented that while he could impose his will on one country’s leader, at No 10 Downing Street, he wasn’t powerful enough to do that with the combined force of 28 countries’ leaders, in Brussels.

From dailysabah.com / © Sun

Meanwhile, during the noughties, the Sun’s sister paper, the News of the World, under the editorship of flame-haired gorgon Rebakah Brooks, was so determinedly on the sniff for a good story that it hacked into the phones of, among others, murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler, dead British soldiers and victims of the 2005 London bombings. This proved too much for even its ghoulish proprietor and he axed the News of the World in 2011. Mind you, he soon replaced it with the Sun on Sunday, so not much changed.

With the Sun leading the way, Britain’s other, supposedly more ‘respectable’ right-wing newspapers – the Daily Telegraph, Daily Mail and Daily Express – happily dived into the same midden of lies, slander and xenophobia, with the result that over the past half-century the popular press in Britain has done much to cheapen public discourse, making it shrill, prurient, mean-spirited and pig-ignorant. Murdoch can also take credit for inspiring the birth, or spawning, of alleged news channel GB News in 2021, which clearly wanted to become the British equivalent of his ghastly Fox News. The conspiracy theories it peddled about the Covid-19 pandemic and Covid-19 vaccines, often voiced by that havering bawbag Neil Oliver, mirror the work Fox News did in the USA to make people resistant to vaccinating themselves against the virus. The fact that Murdoch was one of the first people on the planet to get the vaccine, yet he happily let his media outlets promote scepticism of it among their audience – who tended to be older and more at risk from Covid-19 – shows his ethics are non-existent.

Sadly, in Britain, non-Conservative politicians are so frightened of Murdoch’s newspapers that they feel obliged to cosy up to him. In the late 1990s, Labour Party leader Tony Blair got so thick with Murdoch that he became godfather to one of Murdoch’s kids. In return, the Sun displayed the front-page headline ‘THE SUN BACKS BLAIR’ prior to the 1997 general election that saw him win power. Murdoch’s newspapers subsequently supported Blair during his participation in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, an operation founded on lies and resulting in disaster. I have no doubt that Keir Starmer, the current Labour Party leader, and basically Tony-Blair-lite, will prostate himself before Murdoch in a similar, craven manner.

Though the Nosferatu-esque Murdoch is no longer at the helm of the media empire he’s built, he’s made it clear that he still intends to exert influence from the sidelines. And his son Lachlan is such a piece of work it sounds like that empire will conduct its business with even more malevolence in the future. The fact that Lachlan has just appointed Tony ‘climate-change-is-crap’ Abbott to the Fox board doesn’t bode well.

When Murdoch informed his employees of his decision to step down, he told them to “make the most of this great opportunity to improve the world we live in.” Really, Rupe? Improve? You did nothing to improve the world. Rather, your shitty news outlets helped turn it into a sewer.

© Prana Film / Film Arts Guild