© Pan-Canadian Film Distributors

The cinema at Singapore’s ArtScience Museum is currently showing a season of Christmas-themed films so a few days ago my partner and I visited it to catch a showing of John McTiernan’s action classic Die Hard (1987). My partner hadn’t seen it before and I’d only seen it on a small screen back in the prehistoric days of Betamax video cassettes.

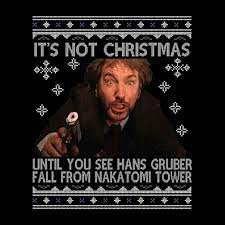

I know every festive season an argument erupts on social media about whether Die Hard is or isn’t a Christmas movie, but seeing it again in 2022 I have to say it seems very Christmassy, much more than I remembered. It’s got Christmas trees, Christmas decorations, Christmas presents, Christmas carols and Christmas Santa hats – one gets planted cheekily on the corpse of a dead terrorist which Bruce Willis’s John McClane sends down in a lift to taunt the remaining bad guys. There’s also a limousine stereo playing Run DMC’s Christmas in Hollis (1987) – ”Don’t you have any Christmas music?” McClane grumbles from the back seat. And Die Hard has Alan Rickman as the villainous and sublimely withering Hans Gruber, who’s a sort of anti-Santa Claus. Gruber’s intonation is priceless as he reads the message McClane has written in blood on the dead terrorist’s chest: “Now I have a machine gun. Ho… ho… ho.”

From amazon.com / © 20th Century Fox

However, I tend not to be aficionado of Christmas movies, for two reasons. Firstly, the way that Christmas is presented in these movies has never corresponded to Christmas as I know it. For example, as a kid, when I heard Bing Crosby crooning White Christmas in the 1954 film of the same name and then looked out of my window in Scotland at the late-December weather, what I saw wasn’t Bing’s white, fluffy snow-scape. What I saw was usually a charcoal-grey sky, leaking charcoal-grey rain down onto a charcoal-grey terrain.

Secondly, Christmas movies are, nearly without exception, rubbish. Most of them eschew anything resembling quality and dial the schmaltz and saccharine up to 11 and assume that’ll satisfy audiences instead – which unfortunately, in many cases, it does. The biggest offender in my opinion is Richard Curtis’s Love, Actually (2003), which I prefer to think of as Shite, Actually. That thing wouldn’t have got anywhere near being a good film even if they’d rewritten the Alan Rickman character and allowed him to start killing people.

Still, there’s a small handful of what are officially deemed ‘Christmas movies’ that I like. Die Hard is one and others include The Snowman (1982), Gremlins (1986), The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), Rare Exports (2010) and The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992) – any film that has Gonzo the Great playing Charles Dickens is fine by me.

There’s also a number of movies that aren’t officially counted as Christmas movies, even though they take place during the festive season, that I like too. No doubt they aren’t included in the accepted Christmas canon because they’re dark in tone and don’t conform to the Richard Curtis Law of Christmas-Movie Pap and Sentimentality. Anyway, it’s in honour of those non-conforming films that I offer the following – my list of favourite alternative Christmas movies.

© Embassy International Pictures / Universal Pictures

Brazil (1985)

Terry Gilliam’s take on George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) has so much going on thematically and visually that it’s easy to forget it’s set at Christmas-time. But while we try to get our heads around the workings of the dystopian society depicted in Brazil – where labyrinthine bureaucratic systems and labyrinthine plumbing systems go wrong with equal regularity, one with deadly results and the other with disgustingly gloopy ones – we’re assailed by Yuletide trappings: Christmas parties, presents, trees, music. There’s a family reading Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843) – just before a terrifying squad of secret-police goons come crashing into their home, wrongly sent by a bureaucratic mistake involving a fly getting stuck inside a typewriter. There are Christmas-decorated department stores that become hellholes – even more hellish than normal at this time of year – when terrorist bombs explode.

On a more symbolic level, the fate that befalls Robert DeNiro’s Harry Tuttle character – surreally engulfed in a mass of paper – suggests the horror of frantic, last-minute Christmas present-wrapping, when you begin to fear the unruly, recalcitrant paper is going to swallow you up. And, late on, when Brazil’s everyman hero Sam (Jonathan Pryce) is imprisoned and facing torture, he gets a visit from Helpmann (Peter Vaughan), a senior official in the Ministry of Information, who ironically shows up wearing a Santa Claus outfit. This underlines the fact that, like many an authoritarian, Helpmann believes he’s being benevolent towards his subjects, though in reality he’s anything but.

© Cinema Entertainment Enterprises

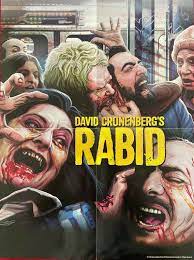

Rabid (1977)

As you might expect, Christmas with Canadian director David Cronenberg is not exactly cosy. Set during the festive season in and around Montreal, Cronenberg’s Rabid tells the tale of a woman (Marilyn Chambers) developing a weird, parasitic skin-puncturing / blood-draining orifice under her armpit following some experimental surgery. She soon becomes a plague-spreader – her new body part infecting people who turn into ravening, blood-craving monsters. One negative thing I always felt about Christmas was the sense of confinement – being stuck indoors because the weather was foul and because there was nothing to do outside anyway due to everything being closed. Rabid conveys a similar feeling by showing Montreal under martial law, its wintry streets silent save for the trucks prowling around removing corpses from the sidewalks. Though a more obvious Christmassy moment is when carnage erupts in a shopping mall and the cops unwittingly gun down the store Santa Claus.

The Silent Partner (1978)

You have to hand it to those Canadians – back in the 1970s, at least, they knew how to stage a dark Christmas movie. Daryl Duke’s The Silent Partner (1978) is an excellent thriller, often amusing but with a few moments of nasty violence to keep the audience on edge. Its villain is the psychotic but intelligent criminal Harry Reikle (Christopher Plummer). Reikle becomes a formidable opponent for – and, as the film progresses, the title’s sinister ‘silent partner’ to – the film’s hero, Miles Cullen (Elliot Gould), a mild-mannered teller working in the Toronto bank that Reikle decides to rob. As it’s Christmas time, and the shopping mall where the bank’s located is overflowing with festive cheer, Reikle carries out the crime disguised as a mall Santa Claus. However, he meets his match in Miles. After Reikle botches the robbery, Miles uses it as an opportunity to fill his own pockets with the supposedly ‘stolen’ money. Reikle is predictably disgruntled by this and a game of cat-and-mouse ensues between them.

The Silent Partner later moves its action to a different time of year, but not before we see Miles at that traditional festive fixture, the staff Christmas party, where he has to listen to his weary, cynical workmates speculating longingly about what they’d do with the stolen money if they had it. His colleagues include a very young John Candy, sporting an alarming 1970s side-parted hairdo.

© Hammer Films / British Lion Films

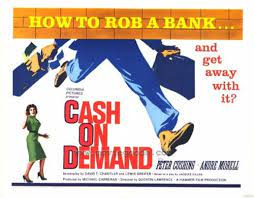

Cash on Demand (1961)

While we’re on the subject of movies about bank workers finding themselves in unhappy alliances with bank robbers, let’s mention the superlative Hammer Films B-movie Cash on Demand, directed by Quentin Lawrence, with Peter Cushing – better known for appearing in the studio’s horror films – as a snotty, uptight bank manager called Fordyce, who’s forced to help a criminal, Hepburn (Andre Morell), intent on robbing his bank. Unlike The Silent Partner, Cash on Demand doesn’t show any violence but a lot of nastiness is implied, with Hepburn matter-of-factly informing Fordyce that he’s kidnapped his family and is going to start torturing them with electrical shocks if he doesn’t cooperate.

And, like The Silent Partner, the attempted robbery in Cash on Demand takes place during Christmas, with a Salvation Army band playing carols outside Fordyce’s bank. Indeed, there’s a Scrooge / Christmas Carol subtext to the plot. Fordyce begins the film as an insufferable prick, contemptuous of his workers, who are more interested in their upcoming Christmas do than the day’s toil at their desks. However, by the ordeal’s end – and after his staff have come to his rescue – Fordyce is a much more appreciative soul, not just of his family but of the people who work for him.

© Amicus Productions / Metromedia Producers Corporation

Tales from the Crypt (1972)

Cushing also appears in the cast of the British horror anthology movie Tales from the Crypt, along with such notables as Sir Ralph Richardson, Ian Hendry and Patrick Magee. Its first episode, All through the House, has the future Alexis Colby and all-round super-diva Joan Collins murdering her wealthy husband on Christmas Eve. Just before she can make the murder – bashing his head in with a poker while he was reading a newspaper, smoking a cigar and wearing a Santa hat – look like an accident – falling down the cellar stairs – fate intervenes in the form of an escaped homicidal maniac who’s prowling outside and is dressed as Santa Claus. We spend the story waiting to hear why he’s dressed as Santa Claus, but we never do – he just is. In the climactic scene, Ms Collins gets her just desserts by being strangled by the maniac. Actually, it looks like he’s just giving her a shoulder massage, but it’s still good, grisly, Yuletide fun.

© Rizzoli Film / Seda Spettacoll / Cineriz

Deep Red (1976)

Dario Argento’s ultra-stylish giallo movie Deep Red (Italian title Profondo Rosso) has David Hemmings investigating a string of gruesome murders around Turin. It’s only tenuously a Christmas movie – the opening scene involves a child witnessing a murder next to a Christmas tree – but generally, in its dark way, the film feels Christmasy. It’s due in part to the richness of Argento’s visuals and in part to the Christmas-like music by Argento’s frequent collaborators, German progressive-rock band Goblin, which alternates between a baroque organ-driven theme and a plaintive child’s refrain. Meanwhile, the cackling clockwork puppet that makes a brief but unforgettable appearance is the sort of Christmas present you’d give to a child you really don’t like.

The Proposition (2005)

What does this Nick Cave-scripted, John Hillcoat-directed Australian western have to do with Christmas? Well, the movie’s finale is a masterpiece of festive-season irony. It has a beleaguered police captain and his wife, played by Ray Winstone and Emily Watson, prepare for their Christmas dinner – turkey, sprouts, pudding et al – with civilised English decorum in the midst of the festering, dusty, fly-ridden hellhole that was the 1880s Australian Outback. There’s also a gang of vengeful, blood-crazed bushrangers on their way intending to kill Winstone and rape Watson, even while Winstone and Watson arrange the Christmas cutlery and crackers on their dining table.

Australians I know have described the weirdness of trying to celebrate a European-style Christmas against the backdrop of Australia’s sweltering December climate, and Cave’s script taps into that weirdness. The Proposition is, incidentally, one of the mankiest films I’ve seen, with the grime-encrusted, matted-haired characters on view paying absolutely no attention to their personal hygiene. The best thing Santa Claus could do for this lot is leave a few bottles of shampoo and conditioner in their stockings.

© UK Film Council / Sony Pictures Releasing

The Proposition would make a great Australian double-bill with my favourite Christmas movie of all time, which is… Drum-roll…

Wake in Fright (1973)

One of the films that helped kick-start what is now known as Australia’s cinematic New Wave, Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright is a reworking of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954) – with a schoolteacher called John Grant (Gary Bond), not some schoolchildren, stranded in an isolated, primitive environment where the onion-skins of civilisation are gradually peeled off him and he descends into savagery. The twist is that Grant isn’t stuck on a desert island but in a hellish Australian Outback town called Bundanyabba, where he’s foolishly gambled away the money he was using to travel home to Sydney. And the brutish behaviour of Bundanyabba’s locals that infects him and drags him down isn’t, it’s implied, any different from that in any other Australian Outback town.

Famous for its scenes of squalor, drunkenness, brawling, vandalism, vomit, sweat-stains, flies, animal-slaughter and Donald Pleasence going bananas, Wake in Fright still qualifies as a Christmas movie. Grant is trying to get back to Sydney for the Christmas vacation and events in Bundanyabba take place against a festive background of Christmas trees, decorations and carols. Meanwhile, a scene near the end where a stained and begrimed Grant wakes up on a floor, haunted by memories from the night before of drinking about a hundred pints, gunning down about two dozen kangaroos, wrecking a pub, and shagging Donald Pleasance, will strike a chord with anyone who’s woken up in a similar state, with similarly traumatic memories, the morning after the work Christmas party.

© NLT Productions / Group W Films / United Artists

Merry Christmas!