© Penguin

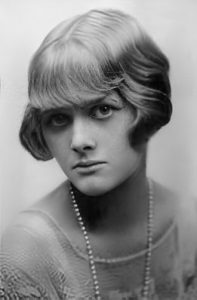

One nice thing that’s happened to me during the past couple of years has been my discovery of how good a writer Daphne du Maurier was. I’d long been aware of her reputation, but until recently the only thing I’d read by her was her famous short story The Birds (1952).

However, I have lately rectified this by working my way through her best-known novels Jamaica Inn (1936), Rebecca (1938) and My Cousin Rachel (1951), as well as her short-story collection Don’t Look Now and Other Stories (1971). Regarding the collection, I didn’t think its title story was quite as good as the famous film it inspired, also called Don’t Look Now, in 1973 – but I thought some of the other stories in it, like A Border Line Case and The Way of the Cross, were crackers.

Now I’ve just completed another book of du Maurier’s short fiction called The Blue Lenses and Other Stories, which was originally published in 1959 as The Breaking Point. I’m happy to report that the tales in it are every bit as satisfying.

Much of the Don’t Look Now collection had a common theme, that of English people travelling abroad and having problems – by turns humorous, serious and horrible – as they leave their comfort zones and encounter the new and the strange. This theme reappears in a couple of stories in the The Blue Lenses one. Ganymede even uses the basic scenario of Don’t Look Now itself, i.e., an English visitor coming unstuck in Venice. The tale, though, isn’t a macabre one but a painful comedy of errors. An older gay Englishman lusts after a teenage Venetian waiter and gets his comeuppance from the lad’s shady relatives, who happily lead him on whilst milking him of his money. Ganymede has a few uncomfortable moments where you wonder if it’s being anti-gay or, alternatively, anti-Italian. But du Maurier – herself believed to have had a lesbian relationship with Gertrude Lawrence – gets away with it, balancing our sympathy for the pathetically naïve Englishman with our satisfaction at him getting his just deserts from the Italians. For all his pitifulness, he is still a predator.

The Chamois has an English couple travelling to some far-flung Greek mountains because the man, obsessed with hunting the goat-antelopes of the title, has been tipped off about the sighting of a notable and shootable specimen there. To get to the peaks that are its territory, they entrust themselves to the care of a goatherd-cum-mountain-guide with a primordial appearance. The woman, narrating the story, describes him as “wrapped in his hooded burnous, leaning upon his crook…” with “the strangest eyes… Golden brown in colour…” There follows a series of psychological revelations about the couple. The man hunts to make up for inadequacies in his psyche and the woman, shall we say, is simultaneously turned off and turned on by his hobby. And a weird, almost mythical narrative unfolds wherein they find it harder and harder to distinguish between the beast they’re seeking and man-beast who’s escorting them.

Similar weirdness occurs in the stories The Pool and The Lordly Ones – the former about a pubescent girl staying at her grandparents’ country house and experiencing strange dreams involving a pond in the woods beyond the garden, the latter about a misunderstood mute child who runs off with some unidentified ‘beings’ who come in the night while he and his family are holidaying on a remote moor. Both contain dashes of W.B. Yeats-style mysticism and Arthur Machen-style folk horror and are among the best stories in the book, even if in The Lordly Ones I saw the ending coming a mile away.

The remaining stories are admirably varied. The Menace is a comedy with a slight science-fictional element, about a movie heartthrob called Barry Jeans who sets hearts aflutter by communicating as few words and expressing as little emotion as possible onscreen. Offscreen he’s not much more vocal or expressive and listlessly leaves all decisions to his bossy wife and his sizeable entourage of hangers-on. Then some new technology ushers in ‘the feelies’, which promise to be as game-changing for the film industry as the arrival of ‘the talkies’. In the feelies, film stars are wired to a machine that transmits their sexual energy – what Austen Powers would call their ‘mojo’ – to the audiences watching them in the cinemas. Barry’s entourage are horrified when preliminary tests suggest that the inscrutable star’s mojo is almost non-existent. So, they embark on a drastic campaign to pep that mojo up. The Menace sees du Maurier taking the mickey out of Hollywood and I suspect it might have been inspired by some unedifying experiences with the place – for example, she was sued for breach of copyright after Rebecca was made into a film in 1939.

The Alibi is the collection’s most twisted tale, about a well-to-do and respectable man who one day seemingly flips: “He was aware of a sense of power within. He was in control. He was the master-hand that set the puppets jiggling.” He walks away from the routines, conventions and obligations of his upper-middle-class existence, invents a new identity for himself and secretly rents a room in a seedy part of London. Initially, he plans to commit murder – but his Nietzschean madness subsides somewhat and instead he starts living a parallel life as an aspiring artist, using the room as his studio. But his project gets knocked for six when the story reaches an unexpected and nasty conclusion.

Different again is The Archduchess, an exercise in magical realism. It describes the final days of a ruling dynasty in a Ruritanian microstate called Ronda, somewhere in southern Europe, which has discovered the secret of immortality. It’s difficult to know where du Maurier’s sympathies lie here. Is she writing in favour of the dynasty and, by extension, of aristocracies and the status quo everywhere? Or is she satirising it? One thing I will say – her account of a devious revolutionary named Markoi, who edits the main newspaper and uses it to seed the minds of the population with doubts, suspicions and eventual paranoia, so as to engineer the downfall of the ruling order, strikes a chord today. Markoi seems all too familiar in a modern world of fake news, where Rupert Murdoch’s Fox News helped propel Donald Trump into the American presidency and, in Britain, the Barclay Brothers’ Daily Telegraph did something similar with Boris Johnson.

Finally there’s the title story, The Blue Lenses, which I found terrifying. Its set-up is a familiar one, about a woman in a hospital recovering from an eye operation who discovers that things suddenly aren’t as they’re supposed to be. But unlike the hero in John Wyndham’s Day of the Triffids (1951), who removes the bandages from his eyes and finds that the world really has gone to hell, the nightmare experienced by the heroine of The Blue Lenses is ambiguous. The surreal, if not grotesque things she sees have a subjective quality and you wonder about her sanity. What makes the story more effective is her decision to pretend to the hospital staff around her that nothing is amiss, while she tries to figure out what’s happening. Her desperate efforts to stay composed heighten the horror of the situation.

As a collection, The Blue Lenses and Other Stories ticks off the checklist of things I want to find in a collection of short fiction: clear, lucid prose, plenty of incident, a variety of tones and genres, the writer’s willingness to use their imagination whether the story is grounded in reality or not, and a commitment at all times to telling an entertaining yarn. It’s another package of du Maurier marvelousness.

From famousauthors.org