© Eon Productions / United Artists

A while ago, my partner and I holidayed in the town of Khao Lak, 60 kilometres from the southeastern Thai resort of Phuket. We saw a brochure for a boat tour in the nearby Ao Phang Nga National Park, which encompasses a large, island-strewn bay in the Andaman Sea. Among the islands visited by the tour was Khao Phing Kan, a location used during the filming of the 1974 James Bond film, The Man with the Golden Gun. It’s now popularly known as ‘James Bond Island’.

Regular readers of this blog will know I’m a connoisseur of all things Bond-related, especially the movies and the original books written by Ian Fleming. So, could I resist an opportunity to visit James Bond island? Of course not.

Not, I should add, that I’m a fan of The Man with the Golden Gun. I think it’s one of the worst films in the Bond franchise. It has Roger Moore in the main role, in only his second outing as 007 but already looking tired – you’re already waiting impatiently for him to regenerate into Timothy Dalton. It has Britt Ekland, required to fill out a bikini but not to do any acting. It has Hervé Villechaize as diminutive henchman Nick Nack (“Dom Perignon soixante-quatre…”) – according to Moore, Villechaize was a lecherous wee pain-in-the-neck in real life. It has Clifton James as redneck comedy-relief American policeman Sheriff Pepper, who happens to be holidaying in Asia when he bumps into Bond – he refuses to have his picture taken with a local elephant, telling Mrs. Pepper: “We’re Demy-crats, Maybelle!” Democrats? That’s a surprise. And it has Lulu hollering the inuendo-riddled theme song: “He’s got a powerful weapon / He charges a million a shot!”

In fact, there are only two good things in The Man with the Golden Gun. One is its villain, the impeccable Christopher Lee as the super-hitman Francisco Scaramanga: “Come, come, Mr. Bond. You disappoint me. You get as much fulfilment out of killing as I do, so why don’t you admit it?” The other is the spectacular scenery. Scaramanga’s island hideaway is supposed to be in waters belonging to ‘Red China’, but the sequence where Bond approaches it in a seaplane was filmed in Ao Phang Nga National Park, with Khao Phing Kan standing in for Scaramanga HQ.

Even if I had hated James Bond Island, the boat trip out to it, which first involved traversing a warren of creeks with mangrove trees cramming their sides, and then passing some of the bay’s islands – giant, towering rocks, their summits and all but their steepest slopes cloaked tightly in trees – was enough to make the day worthwhile. Those islands, which’d looked pretty spectacular during The Man with the Golden Gun’s airborne scenes, with the cameras tracking Bond’s seaplane, seemed absolutely awesome when I was looking up at them from sea-level. Among the things I compared the fantastic shapes of these islands to in my notebook entries that day were: ‘fangs’, ‘ruined, vegetation-shrouded fortresses’, ‘herds of grazing prehistoric beasts’, ‘monstrous haystacks’, ‘mossy tombstones’ and ‘giant standing stones’. We passed one vaguely curved island with curious round protuberances on either side, like ears. Our guide said it was nicknamed ‘The Dog’.

As it turned out, we spent just 25 minutes on James Bond Island, which felt an adequate length of time. It was very busy with tourists. We guessed as much when we approached it and saw the great number of long boats, with varnished hulls and club-shaped bows, lined along its landing area. If Scaramanga was around today, he’d be erecting angry signs saying GET OFF MY LAND in response to the hordes of visitors. Maybe even firing volleys of his legendary golden bullets at the trespassers.

Despite the crowds, I was delighted to see Ko Ta Pu, the 20-foot-high, precarious-looking limestone rock that stands off the island’s shore and is shaped like an extracted tooth. In The Man with the Golden Gun, Scaramanga – who, unconvincingly, is depicted as a pioneer of green energy as well as a deadly hitman – has solar panels extend up from the top of Ko Ta Pu and collect enough sun’s energy to power an energy-beam gun, with which he destroys Bond’s seaplane. Getting a photo of this remarkable stub of rock was difficult, with so many people posing for selfies in front of it. But I managed in the end.

The island’s other striking feature is a huge, triangular opening behind the main beach, caused by seismic action. A giant slab of rock apparently broke free and ended up tilting steeply against the rest of the rock-mass there. Beneath it, looking up at its bulk and angles, you have a lurking fear it could topple the rest of the way and pulverize everything below, you included. It was here that we incurred the wrath of a large, bikinied and ignorant Western woman who’d been posing lasciviously for multiple photos in front of the formation and didn’t appreciate us strolling into her camera-frame.

As well as being infested with tourists, the island’s main beach was infested with stalls selling tourist tat. I was disappointed that no 007-themed merchandise was on sale – not even replicas of Christopher Lee’s golden gun. I guess then-Bond-producers Cubby Broccoli and Albert Saltzman refused to license the Bond brand to the Thai tourist authorities and the vendors here could sell only generic, er, nick-nacks… Weirdly, one Western-movie item that was on sale were figurines of Groot, the tree-like creature that features in the Guardians of the Galaxy (2014-23) movies. That’s because if you look at Ko Ta Pu long enough, you begin to see its resemblance to the head of Groot.

In fact, Khao Phing Kan, James Bond Island, wasn’t the only movie-connected island we visited in the Andaman Sea. A few days later, we went on a second boat trip, this time to the Phi-Phi-Phi Islands south of Ao Phang Nga National Park. One of the stops we made there was at Ko Phi Phi Lee, home to the now-famous Maya Bay.

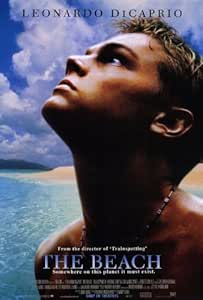

© Figment Films / 20th Century Fox

This was where in 2000 Danny Boyle filmed The Beach, based on the 1996 novel of the same name by Alex Garland. This movie was troubled in a couple of different ways. Originally, Ewan McGregor was lined up to star in it but, to his disgust, he was ultimately passed over in favour of Leonardo DiCaprio, then seen as a much more bankable actor because he’d played the hero in James Cameron’s world-beating Titanic (1998). This led to McGregor falling out with Boyle and the pair didn’t talk to each other for many years afterwards. More seriously, it was alleged that during production the filmmakers caused serious damage to Maya Beach’s ecosystems by ‘landscaping’ – i.e., bulldozering – part of it to make it more ‘paradise-like’.

We arrived at the northern side of Ko Phi Phi Lee and disembarked onto a precariously swaying, floating quay. Then, filing along a slightly elevated wooden walkway – no doubt there to prevent the sand, soil, rocks and plants being pulverized under the feet of countless visitors – we made our way into the island’s interior. The walkway was divided into two narrow lanes, with tourists streaming along in both directions. It arrived at a wider wooden platform in the middle of the island, where there were facilities such as toilets, souvenir stalls and eateries and where you could step down onto the surrounding ground. Two further walkways bifurcated off on its far side, both leading to the bay. We followed the slightly less busy one.

Maya Bay itself was certainly picturesque, its white sand and turquoise water encircled by high cliffs and crags. But it swarmed with the inevitable tourists, taking the inevitable photos and selfies. Our guide told us we should visit it at the time of Chinese New Year. Then, apparently, it gets really busy.

Although The Beach received middling reviews, it was reasonably successful – enough for it to cause the heavy tourist traffic to Ko Phi Phi Lee and Maya Beach. Things got so bad that in 2018 the Thai government banned all tourists from it, so that work could be done to restore its now-shattered environment. It wasn’t reopened to visitors until 2022, at the tail-end of the Covid-19 pandemic. Tour groups, like ours, are allowed only an hour on the island, and it also gets a two-month, tourist-free breather every year, from August 1st to October 1st.

This makes me wonder what would have happened if Danny Boyle had made The Beach with Ewan McGregor, rather less of a draw than Leonardo DiCaprio. (Sorry, Ewan.) It would have meant: (1) a less successful film, seen by fewer people; (2) fewer tourists flocking to Maya Bay, which would have put it under less environmental strain; and (3) Trainspotting 2 (2017) being made years earlier than it was, because Boyle and McGregor would never have fallen out and then needed ages to make up. Win-win all round, I’d say.