© Icon Productions / Ladd Company / Paramount Pictures

I’ve just realised that it’s the 30th anniversary of the release of Mel Gibson’s woad-slathered and not-entirely-historically-accurate epic Braveheart (1995). This was the movie that added the battle-cry “FREEE-DOM!” to the chorus of things you hear outside Scottish pubs at closing time (along with “SHUT YER PUSS!” and “I’M OOT MA FACE!”). Thus, it seems an appropriate time to post this tribute to one of the very best things in Braveheart, James Cosmo.

I’ll make no bones about it. I f**king love the mighty Scottish character actor James Cosmo.

These days the hulking, craggy and formidable Cosmo – whose visage is usually bedecked with long white tresses of hair and a moustache that on anyone else would suggest ‘ageing hippy’, but on him suggest ‘someone you really don’t want to mess with’ – seems most familiar when he’s clad in armour and wielding a broadsword. He’s carved a profitable niche for himself playing characters in movies and TV shows set in the ancient world, the Middle Ages and medieval fantasy lands, such as Highlander (1986), Braveheart (1995), Ivanhoe (1997), Cleopatra (1999), Troy (2004), The Lost Legion (2007), Game of Thrones (2011-2013), Hammer of the Gods (2013), Ben–Hur (2016), Outlaw / King (2018) and The Last Redemption (2024) However, Cosmo, who was born in Clydebank and attended the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Dramatic Art and the Bristol Old Vic Drama School, worked long and hard on television before he cornered the market for playing grizzled bear-like warriors in historical and fantasy epics.

He earned his acting spurs during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s in a long line of TV shows and TV plays. The better-known titles he appeared in include Doctor Finlay’s Casebook (1965 & 69), Softly Softly (1969), UFO (1971), The Persuaders (1971), Sutherland’s Law (1972), Quiller (1975), Survivors (1976), George and Mildred (1977), The Sweeney (1978), The Onedin Line (1979), The Professionals (1979), Strangers (1981), Minder (1984) and Fairly Secret Army (1984). The most distinguished TV productions from this time to feature Cosmo were probably Nigel Kneale’s haunted-house-cum-sci-fi-horror-story The Stone Tape (1972) – its influence is detectable in many films and TV shows made since then, including the recent In the Earth (2021) and Enys Men (2022) – and the 1974 Play for Today adaptation of John McGrath’s The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black Oil, the most important piece of political theatre to surface in Scotland during the 1970s.

© Hammer Films / ITC Entertainment

I was in my mid-teens when I started to notice Cosmo as an actor. He played a villain in an episode of The Hammer House of Horror (1980), which climaxed with him driving a cleaver into the skull of the fragrant Julia Foster, something that must have shocked those viewers who remembered her from the wholesome 1968 musical with Tommy Steele, Half a Sixpence. That grisly scene made a big impression on me, although nothing compared to the impression it obviously made on Julia Foster. He also appeared in 1981’s The Nightmare Man, a cheap but creepy BBC mini-series scripted by the great TV writer Robert Holmes about a mysterious killer stalking a fogbound Scottish island. The Nightmare Man saw Cosmo in good company, as the cast also included Celia Imrie, James Warwick, Tom Watson and an equally craggy Scottish character actor, the late Maurice Roeves.

By the late 1980s Cosmo was becoming the go-to guy if you needed an imposing Scottish hard man in your production. For example, he appeared in Brond, a 1987 Channel 4 adaptation of the novel by Frederic Lindsay, set in Glasgow and a thriller involving conspiracies and terrorism. It tells the story of a hapless innocent, played by a very young John Hannah, who falls under the influence of the mysterious and sinister Brond of the title and ends up being accused of carrying out a political assassination. Brond is played by the portly and menacing Stratford Johns, although Cosmo is no less intimidating as Primo, the silent, lethal hulk who acts as Brond’s henchman. Two years later Cosmo had a similar role in the glossy Glasgow-set BBC thriller The Justice Game, in which this time he terrorised Dennis Lawson – yes, Wedge Antilles in the original Star Wars trilogy (1977-83) and real-life uncle of Ewan MacGregor.

Meanwhile, in 1986, Cosmo had appeared in Russell Mulcahy’s Highlander, the fantasy movie about immortal beings feuding throughout human history. He plays a member of the MacLeod clan in the medieval Scottish Highlands and he helps Christopher Lambert to escape when their superstitious fellow clansmen get alarmed about how, within hours, Lambert’s battle-wounds miraculously heal up. Not only does Lambert turn out to be one of the immortals but he’s also the world’s most French-sounding Scotsman. Later in the movie he encounters Sean Connery, who’s another immortal and also the world’s most Scottish-sounding Spaniard. (The scene where Lambert explains to Connery what a haggis is has to be heard to be believed.) Totally scatty, but loveable, I suspect Highlander was the movie that helped Cosmo secure the sweaty, muddy sword-and-sandals roles he became well-known for in the 1990s and 2000s.

© Thorn EMI Screen Entertainment / 20th Century Fox

The key sword-and-sandals role for Cosmo arrived in 1995 with the Mel Gibson-directed, Mel-Gibson-starring Braveheart, in which he plays Campbell, father of Hamish, best friend to 13th / 14th-century Scottish freedom-fighter William Wallace. Playing Hamish is the huge, ursine Brendan Gleeson, who later found fame in Michael McDonagh’s glorious 2008 comedy-thriller In Bruges. If anyone is even huger and more ursine-looking than Gleeson and could convincingly play his dad, it’s Cosmo. In reality, the two actors are only seven years apart in age.

Seven years old is also about the age that Isabella of France would have been in real life during the events depicted in Braveheart. In the film, she’s played by Sophie Marceau (in her late twenties at the time), is presented as English King Edward I’s daughter-in-law and has a sizzling romance with Gibson’s Wallace. This sums up the film’s cavalier disregard for historical accuracy. (It also gave stand-up comedian Stewart Lee material for a routine about William Wallace being a paedophile, which he bravely delivered in Glasgow.) The film is also anti-English to a degree that wouldn’t be acceptable against any other ethnic, national or cultural group in a Hollywood movie. But in the film’s defence I’ll say that the battle scenes, for their time, were excellent. And the supporting cast that Gibson assembled – Cosmo, Gleeson, Marceau, David O’Hara, Patrick McGoohan, Catherine McCormack, Angus McFadyen, Ian Bannen – is excellent too.

As Campbell Senior, Cosmo comes across as a near-unstoppable force of nature. He gets skewered with an arrow at the initial uprising in Lanark but ignores that and carries on fighting. He gets his hand chopped off at the Battle of Stirling but ignores that and carries on fighting too. Even when someone embeds an axe in his stomach at the Battle of Falkirk, he keeps going long enough to deliver a moving farewell speech to Gleeson.

A year later Cosmo appeared in Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting, the movie that gave the world an equally potent image of Scotland, if a rather different one from that given by Braveheart. In fact, Trainspotting, based on the 1993 novel of the same name by Irvine Welsh, is the modern-urban-Scottish-junkie yin to Braveheart’s heroic-medieval-Scottish-warrior yang. In Trainspotting, he plays another dad, this time of Ewan MacGregor’s Renton character, a junkie so desperate for his next fix that he’ll crawl into the shit-encrusted bowl of the Worst Toilet in Scotland to get it.

While it’s nice to see his face in the film, Cosmo is kept very much in the background. Gratifyingly, he got more to do when Boyle, MacGregor and the rest of the Trainspotting crew finally reunited in 2017 to make Trainspotting 2, based loosely on parts of Welsh’s original novel that were left out of the first film and on its 2002 literary sequel Porno. Trainspotting 2 concludes — in an ending that radically differs from that of Porno — with Renton deciding home is the best place for him. So he gives his now-widowed father a hug and moves into the latter’s spare bedroom (where, of course, he promptly starts dancing to Iggy Pop’s 1977 classic, Lust for Life).

© Material Pictures / Highland Midgie / Amazon Studios

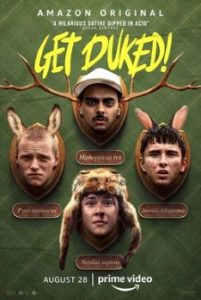

After Braveheart, Cosmo was kept busy with sword-wielding roles, including 12 episodes as Jeor Mormont in Game of Thrones. However, he’s also become something of a fixture in recent British and Irish horror / thriller movies – he’s appeared in Urban Ghost Story (1998), Outcast (2009), The Glass Man (2011), Citadel (2012), January (2015), Dark Signal (2016), Malevolent (2018), The Hole in the Ground (2019), Get Duked! (2019), The Kindred (2022) and The Beast Within (2024). Of these, I enjoyed the horror-comedy Get Duked! the most. It’s the story of four lads tramping around in the Scottish Highlands whilst trying to earn their Duke of Edinburgh Award – and realising they’re being hunted by a weird pair of aristocratic psychopaths (played by Eddie Izzard and Georgie Glen). Cosmo turns up in it as a farmer the boys encounter in the course of their misadventures.

It’s normal for secondary characters in horror films to be nothing but cannon fodder – they soon get killed off to ratchet up suspense and demonstrate the power and evilness of the monster or villain. But Get Duked! makes those secondary characters interesting, keeps them around and has a lot of fun with them. Which is smart because it has a splendid supporting cast: Cosmo, Jonathan Aris and, as bumbling police officers, Kate Dickie, Alice Lowe and another veteran Scottish actor, Brian Pettifer. Despite first being sighted in a boiler suit and at the wheel of a tractor, Cosmo’s character proves to have a side not normally associated with Highland farmers. He has a fondness for certain hallucinogenic substances and is soon grooving to a mix CD that the lads give him.

Unexpectedly, Cosmo has a further speciality, which is for playing Santa Claus. According to his IMDB profile he’s now filled the furry boots of Saint Nick on three different occasions, most famously in the 2005 Disney version of C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

He’s a pleasingly ubiquitous and varied performer. In the past decade I’ve seen him in things as different as SS-GB (2017), the BBC drama serial based on Len Deighton’s 1978 alternative-history thriller and set in a Nazi-Germany-controlled London in 1941; Wonder Woman (2017), one of the few decent DC Comics movie adaptations, in which he plays Field Marshal Douglas Haig; and the HBO miniseries Chernobyl (2019), where he’s one of the miners drafted in to dig a tunnel under the stricken plant’s melted uranium and prevent it from leaking into the Black Sea. His IMDb page currently lists no fewer than eight upcoming projects, so clearly he’s keeping busy. Meanwhile, on the non-acting side, he was a contestant in the 2017 series of Celebrity Big Brother and has recently been doing a speaking tour entitled An Evening With James Cosmo.

Though he’s well into his eighth decade, James Cosmo looks as daunting as ever. His visage, bulk and general demeanour suggest a man whom you definitely don’t want to give any cheek to. And if you are foolhardy enough to give him cheek, he’ll probably kebab you on a long rusty medieval pike and simultaneously slash your throat with a sgian dubh. That’s the sort of guy I’d like to be when I become eligible for my bus-pass.

© HBO Entertainment / Television 360