© Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer

I’ve been busy lately and unable to post much on this blog. Here’s a reposting of something that first appeared here in 2019.

During the 1970s, when I was a kid and when I absorbed cultural influences like a sponge, crime movies made in the United Kingdom were rarer than hen’s teeth. That’s hardly surprising. During that decade, the British film industry practically died on its arse.

And yet, as a kid, I got the impression that 1970s Britain was so crime-ridden it was dystopian. It was a place where every bank and security van was in constant danger of being attacked by beefy men with sawn-off shotguns and stockings pulled over their heads. Where every street was the potential scene of a violent punch-up and every road was the potential scene of a destructive car chase. Where the police force scarcely seemed any better than the villains, its ranks composed of hard-boozing, chain-smoking, foul-mouthed thugs wearing kipper ties. Really, at times, I must’ve been too afraid to leave my house.

This is because 1970s British television was awash with crime and cop shows, often violent and populated by low-life characters on both sides of the law: for example, Special Branch (1969-74), Villains (1972), New Scotland Yard (1972-74), The Sweeney (1975-78), Gangsters (1975-78), The XYY Man (1976-77), Target (1977-78), Out (1978), Hazell (1978-79) and Strangers (1978-82). Impressionable kids like me would act out things we’d seen on TV the night before, so that at breaktimes school playgrounds reverberated with shouts of “You’re nicked, sunshine!” and “You grassed me off, you slag!” and “We’re the Sweeney, son, and we haven’t had any dinner!” My parents were happy to let me watch such programmes. As long as I wasn’t watching that horror rubbish, which had been scientifically proven to be bad for you.

I suppose that many British directors, writers and actors who would have plied their trade on the big screen, if Britain’s film industry hadn’t been moribund, found themselves plying it on the small screen instead. This helped inject some uncompromising cinematic rawness into the domestic TV crime genre. But the cinematic counterpart of that genre seemed non-existent.

Well, almost non-existent. A few crime movies did get made in 1970s Britain and these exert a fascination for me today. Only two of them ever achieved a degree of fame and the rest are virtually forgotten, but I find all of them cherish-able. Here are my favourites.

© MGM EMI

Get Carter (1970)

Everyone knows this 1970s British crime film, although I don’t recall it getting much attention until the 1990s, when thanks to Britpop, Damien Hirst, etc., the ‘cool Britannia’ scene took off and Get Carter’s star Michael Caine suddenly became a retro-style icon. Ironically, Caine’s nattily dressed Jack Carter and Roy Budd’s edgy jazz score aside, there isn’t much in the Mike Hodges-directed Get Carter that feels stylish. The drab, monochrome terraced streets of Newcastle-upon-Tyne – if the film’s premise is that Michael Caine has returned to his hometown to sort out trouble, whatever happened to Caine’s Geordie accent? – the shabby pubs, the seedy racecourses, the shit clothes and haircuts, the Neanderthal attitudes… It’s depressing, actually. It’s a provincial Britain where the Swinging Sixties have truly burned themselves out – if the Swinging Sixties ever reached provincial Britain in the first place.

Caine gets all the acting accolades for Get Carter but the film wouldn’t be what it is without its excellent supporting cast: Alun Armstrong, Britt Ekland, George Sewell, Tony Beckley and playwright and occasional actor John Osborne. Best of all, there’s Ian Hendry as the film’s weasly villain, Eric Paice. “Do you know,” Carter tells Paice at one point, “I’d almost forgotten what your eyes look like. They’re still the same. Piss-holes in the snow.” Hendry was originally meant to play the virile Carter, but by 1970 his fondness for the booze had taken its toll and he was demoted to the secondary role of Paice, which supposedly caused tension and resentment during filming. Thus, Caine may have enjoyed the irony of the film’s climax, which sees Carter force-feed Paice a bottle of whisky before clubbing him to death with a shotgun.

Villain (1971)

Villain has Richard Burton, no less, in the role of a gay, mother-fixated and paranoidly violent gang-boss who, against the counsel of wiser heads, gets himself involved in a raid on a factory’s wages van that ultimately causes his downfall. Meanwhile, trying to stay in one piece is Ian McShane, playing a smooth but unimportant pimp who has the unenviable job of being both the object of Burton’s affections and the victim of his sadistic rages.

Villain also has a wonderful supporting cast – T.P. McKenna and Joss Ackland as fellow gang-bosses, Del Henney, John Hallam and (alas, the recently-departed) Tony Selby as henchmen, and Nigel Davenport and Colin Welland as the coppers doggedly trying to bring Burton to justice. (Interestingly, McKenna, Henney and Welland all turned up in the cast of Sam Peckinpah’s troubling Straw Dogs, made the following year.) The film suffers from having too many sub-plots, though the one where McShane helps Burton escape the law by getting a sleazy Member of Parliament who’s used his pimping services to testify for him is memorably believable and nauseating. Played by Donald Sinden, you never hear which political party the MP belongs to, but you can guess.

Sitting Target (1972)

Ian McShane had to suffer some dysfunctional relationships in early 1970s British crime movies. No sooner had he finished being Richard Burton’s lover / punchbag in Villain than he had to cope with being best friend to a psychotic Oliver Reed in Sitting Target, directed by the underrated Douglas Hickox. With McShane in tow, Reed escapes from prison early in the film, determined to catch up with his wife Jill St John and give her what’s coming to her. Reed doesn’t want revenge on St John, as you might expect, for her terrible performance as Tiffany Case in Diamonds are Forever (1971). No, it’s because he’s discovered she’s betrayed him for another man. The film’s big twist, when we find out who that other man is, isn’t altogether a surprise.

Sitting Target has many pleasures, including Edward Woodward playing a policeman assigned to protect St John against the marauding Ollie. But nothing quite matches the thrilling early sequence where our two anti-heroes, plus a third convict played by the always-entertaining character actor Freddie Jones, bust out of prison in desperate, skin-of-the-teeth fashion.

The Offence (1972)

Okay, Sidney Lumet’s The Offence (which I’ve previously devoted a whole blog-entry to) isn’t really a crime movie. It’s a psychological study of a macho but troubled police officer (Sean Connery) going over the edge when a hunt for a child-killer, and the provocations of the suspect the police have pulled in for questioning (Ian Bannon), push too many buttons on his damaged psyche. But the film has that grim 1970s aesthetic that more conventional British crime movies of the period are so fond of – drab housing estates, anonymous tower blocks, serpentine pedestrian bridges. Its supporting cast also includes strapping character actor John Hallam who, although he’s probably best remembered as Brian Blessed’s Hawkman sidekick in 1980’s Flash Gordon, was a fixture in crime movies at this time. So, I’m putting The Offence on my list.

© American International Pictures

Hennessy (1975)

I’m also conflicted about adding Don Sharpe’s Hennessy to this list because it’s about terrorism rather than crime. Indeed, its story of a former IRA explosive expert (Rod Steiger) who decides to destroy the British government and the Queen by blowing up the state opening of parliament after his wife and child are killed by the British Army, makes it the first movie to tackle the issue of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. However, as the final film on the list is choc-a-bloc with IRA men, and as Richard Johnson gives a lovely performance as the weary, dishevelled, cynical copper – is there any other type in British crime movies? – trying to thwart Steiger’s plan, I thought I’d give it a mention.

The film is admittedly patchy but it has a top-notch cast that also includes Lee Remick, Trevor Howard, Eric Porter, John Hallam (again), Patrick Stewart (bald as a coot even then) and a super-young Patsy Kensit playing Steiger’s ill-fated daughter. The climactic scenes set in the House of Commons, involving the Queen, landed the filmmakers in hot water because they used real footage that Buckingham Palace had approved without knowing it was going to end up in a film. Also, the film’s subject, an incredibly touchy one at the time, meant that Hennessy scarcely saw the light of day in British cinemas.

Brannigan (1975)

Brannigan – also directed by Douglas Hickox – is the joker in this pack. It features John Wayne as a tough American cop who arrives in a London of bowler hats, brollies and historic landmarks that exists only in the imagination of Hollywood scriptwriters, and who then causes mayhem as he behaves like a Wild West sheriff dealing with an unruly frontier town. This involves such memorable sequences as Wayne doing an Evel Knievel-style car stunt where he hops across Tower Bridge while it parts to let a ship pass below. And Wayne triggering a cowboy-style brawl in a pub near Leadenhall Market. And Wayne roughing up a minor villain played by the cinema’s greatest Yorkshireman, Brian Glover. (“Now would you like to try for England’s free dental care or answer my question?”) If you’re in the wrong mood, Brannigan is the worst film ever made. If you’re in the right mood, it’s the best one.

© United Artists

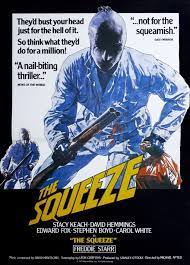

The Squeeze (1977)

Barely had John Wayne swaggered through the London underworld than another Hollywood star did too in Michael Apted’s The Squeeze – Stacy Keach, although playing an English private eye with an industrial-strength drink problem. During occasional moments of sobriety, Keach investigates the kidnapping of his ex-wife (Carol White). She’s remarried a posh security officer (Edward Fox) tasked with overseeing the delivery of large sums of money. Keach finds himself tangling with a kidnap gang planning to force Fox to help them mount an armed robbery.

The Squeeze suffers from being overlong, with too much time spent wallowing in Keach’s alcoholism. But its good points outweigh this. I like its depiction of late 1970s multicultural London and its sympathetic portrayal of Keach’s Jamaican neighbours. Also, Stephen Boyd (who died soon after the film’s completion, aged just 45) and David Hemmings give good turns as the villains. Allowed to use his native Northern Irish accent for a change, Boyd disturbingly plays a well-heeled crime-lord who dotes over his own family whilst having zero empathy for the family he’s threatening to destroy with his kidnapping scheme. Meanwhile, Hemmings is good as a pragmatic career criminal who doesn’t share his boss’s sunny optimism about things.

And connoisseurs of 1970s British popular culture will be fascinated to see anarchic comedian Freddie Starr play Keach’s best mate, a reformed criminal trying to make a living as a taxi driver. Indeed, such is Starr’s loyalty to Keach that he saves his neck three times at the end of the film, including by running the villains off the road in his taxi. Starr, who died in 2019, was from all accounts an unreconstructed arsehole in real life. Therefore, remember him this way.

© Warner Bros. Pictures

Sweeney II (1978)

The greatest of all 1970s British cop shows, The Sweeney got two movie spin-offs, Sweeney! In 1977 and Sweeney II. I don’t think Sweeney!, which involved Flying Squad heroes Jack Regan (John Thaw) and George Carter (Dennis Waterman) in an espionage plot, is much cop, but Sweeney II captures the spirit of the TV series. It has Regan and Carter on the trail of a gang who spend most of their time living it up in Malta as wealthy British ex-pats, but who return to Britain from time to time to stage vicious, take-no-prisoners bank robberies. As well as marrying bloody, sawn-off-shotgun-powered violence with some off-the-wall humour, Sweeney II manages to be topical too. London’s real Metropolitan Police force was investigated for corruption in the late 1970s. The film reflects this with the character of Regan’s commanding officer, played by the excellent Denholm Elliot, who’s facing a long stretch in prison on account of being “so bent it’s been impossible to hang his pictures straight on the office wall for the past twelve months.”

The Long Good Friday (1980)

Although it was released at the start of the 1980s, John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday was made in 1979 and so I’m classifying it as a 1970s film. It definitely feels the end of a particular era with its tale of an old school London gangster (Bob Hoskins) convinced he’s about to make a mint in the brave new world of Thatcherite London where everything is up for sale to the corporations and developers. That’s until one day when he suddenly finds himself tangling with a ruthless foe, the IRA, who make him look hopelessly out of his depth.

The final scene sees Hoskins become a prisoner in his own, hijacked car and get driven to his doom – an IRA man played by a youthful Pierce Brosnan snakes up from behind the front passenger seat to hold him at gunpoint. Although Hoskins doesn’t speak, the succession of emotions that flit across his face as it dawns on him that he had it all, but now he’s blown it all, make this the most powerful moment in British crime-movie history.

© Black Lion Films / Handmade Films / Paramount British Pictures