© Midnight Street Press

On this blog one year ago, I remember writing a post that bid an unfond adieu to the outgoing hellhole plague-year of 2020. However, the post also welcomed 2021 with some expressions of mild optimism. After all, vaccines were being developed against Covid-19, the main reason for 2020’s hideousness. And that man-slug of evil, Donald Trump, had just been defeated in the US presidential election.

Well, I’m not making that mistake again. I’m not expressing even faint optimism about 2022, seeing as 2021 was nearly as dire as its predecessor.

While the vaccines arrived – and having been double-jabbed and boosted courtesy of Sri Lanka’s healthcare system, I’m feeling a lot safer personally – it’s depressing that much of the world’s population remains unvaccinated. Economics and politics have denied many people access to vaccines in the Global South. Gordon Brown isn’t someone I normally agree with, but he’s absolutely right when he argues that the estimated 23.4 billion dollars it’d cost to roll out vaccines to everyone would be a wise investment for the world’s rich countries. (It’s also a fraction of what’s been spent on certain recent wars.) Meanwhile, anti-vaxxers continue to boggle the mind with their stupidity. It takes unfathomable levels of dumbness to believe that getting a vaccine means having Bill Gates seed your body with micro-transmitters. As a result, for years to come, unvaccinated humans will provide a giant petri dish for new Covid variants to mutate and develop.

As for the USA, it looks increasingly likely that the Republican Party, with Trump quite possibly at its head again, will be back in control of the White House in 2024. They won’t win the popular vote, but the voter suppression, voting-law changes and replacement of election officials they’re currently enacting by stealth in the crucial ‘swing’ states will get them over the line. At which point, the world’s most powerful nation will become a totalitarian state.

Anyway, enough of the gloom. For me, 2021 wasn’t a disappointment in one respect, at least. During the year I got a fair number of stories published, under the pseudonyms Jim Mountfield (used for my horror fiction) and Rab Foster (used for my fantasy fiction). There follows a round-up of those stories, with information about where you can find them.

© DBND Publishing

As Jim Mountfield:

- In January 2021, my story Where the Little Boy Drowned was published in Horrified Magazine. A ghost story (with a smidgeon of J-Horror), it was about a flooded river, a forgotten childhood tragedy and – appropriately for January – a New Year resolution that goes wrong. It can be read here.

- February saw The Stables – another ghost story, this time about three girls on holiday in the countryside who enter a seemingly deserted farmstead searching for a riding school – appear in Volume 16, Issue 13 of Schlock! Webzine. Kindle and paperback versions of the issue are available here.

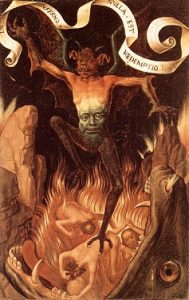

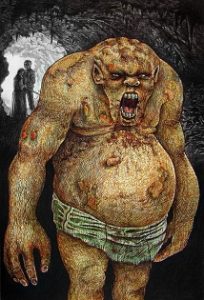

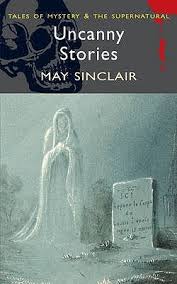

- Later in February, When the Land Gets Hold of You, another story set on a farm, was featured in an anthology from DBND Publishing called The Cryptid Chronicles. As its title suggests, the stories in this collection concerned cryptids, that pseudoscientific category of animals that some people claim to exist but nobody has ever conclusively proven to exist, such as Chupacabra, the Jersey Devil and Nessie. The cryptids in my story were based on redcaps, the malevolent fairies that legends say inhabit the peel towers of Scotland’s Borders region. The Cryptid Chronicles can be bought here.

- Shotgun Honey, a webzine devoted to the ‘crime, hardboiled and noir genres’, published my story Karaoke in March 2021. The story is about – surprise! – karaoke and it can be read here.

- In July, I was pleased to have my story Ballyshannon Junction included in the collection Railroad Tales, from Midnight Street Press. The stories in Railroad Tales involved both ‘railroads, trains, stations, junctions and crossings’ and the ‘horrific, supernatural or extraordinary’. Ballyshannon Junction met this brief by being set in an abandoned railway station in Northern Ireland during the Troubles and featuring a main character who’s plagued by possibly supernatural visions. It also allowed me to use as inspiration the real-life Bundoran Junction station-house and grounds in County Tyrone, where my grandparents lived when I was a kid. Railroad Tales can be purchased from Amazon UK here and amazon.com here.

- A story inspired by a very different period in my life – when I worked in Libya – appeared in Volume 16, Issue 21 of Schlock! Webzine in October. The story was called The Encroaching Sand and the issue is available in kindle and paperback forms here.

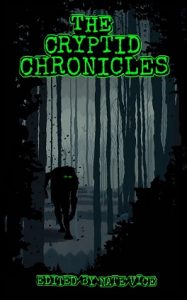

- Also in October, my story Bottled Up was included in the anthology Horror Stories from Horrified (Volume 2): Folk Horror, published by Horrified Magazine. Folk horror is defined by Wikipedia as “a subgenre of horror… which uses elements of folklore to invoke fear in its audience. Typical elements include a rural setting and themes of isolation, religion, the power of nature, and the potential darkness of rural landscapes.” Accordingly, Bottled Up was set in that rural and folkloric part of England, East Anglia, and featured the remnants of a cult that worship a pagan sea deity. The anthology can be purchased here.

- Finally, my story Problem Family – about, unsurprisingly, a problem family, but also with a dash of H.P. Lovecraft – appeared in Horla in December. Currently, it can be read here.

© Horrified Magazine

As Rab Foster:

- In May, Perspectives of the Scorvyrn was published in Volume 16, Issue 16 of Schlock! Webzine. This tale attempted to subvert the more macho, musclebound, boneheaded conventions of that sweaty sub-genre of fantasy fiction, the sword-and-sorcery story. For one thing, it was told from multiple viewpoints and, for another, it was written in the present tense. Conan the Barbarian would not have approved. Kindle and paperback versions of the issue can be obtained here.

- In July, my 13,000-word story The Theatregoers appeared in the Long Fiction section of Aphelion. It can be accessed here.

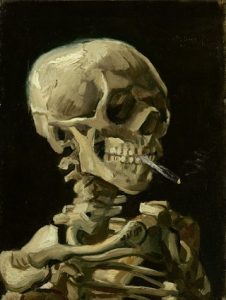

- October saw The Orchestra of Syrak, a story inspired by the phantasmagorical (if overly verbose) work of pulp writer Clark Ashton Smith, appear in the 116th issue of Swords and Sorcery Magazine. You can read it here.

- And in November, Parallel Universe Publications unveiled a collection entitled Swords & Sorceries: Tales of Heroic Fantasy, Volume 3, which included my story The Foliage. An extremely handsome volume (thanks to its illustrations by the talented artist Jim Pitts), kindle and paperback copies of it can be ordered from Amazon UK here and amazon.com here.

© Aphelion

And that’s that – proof that 2021 wasn’t so bad for me writing-wise, even though it sucked on most other levels.

I shan’t tempt fate by making any optimistic predictions about 2022, but let’s just hope it turns out to be better than its two predecessors. And yes – I’m touching a large wooden surface as I write this – a Happy New Year, everyone!