© The Mirisch Company / United Artists

I read recently that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences – better and less grandiosely known as the folk who dole out the Oscars every year – are currently considering creating a new Oscar that will honour the work of the movie industry’s stunt performers. A yearly award for the film featuring the best stunt-work looks a real possibility thanks to the efforts of Chad Stahelski, director of the John Wick series (2014-23). He commented last month, “We’ve been meeting with members of the Academy and actually having these conversations… Everybody on both sides wants this to happen. They want stunts at the Oscars. It’s going to happen.”

Also creating a buzz lately about stunt-work – proper, practical stunts carried out by real people, as opposed to artificial action-sequences created with cartoony, shit-looking Computer-Generated Imagery – has been the trailer for the new Mission Impossible movie. This is framed by a stunt involving the world’s most famous scientologist in which he deliberately barrels off a very high cliff. The last person to do this so spectacularly was Roger Moore – or more accurately, stuntman Rick Sylvester – in the pre-credits sequence of The Spy Who Loved Me (1978).

Anyway, now seems an opportune time to dust down and repost this piece about my favourite practitioners of the art of stunt-work, which originally saw the light of day in 2018.

In my boyhood, there were no personal computers, video games or Internet to keep me inside the house. For amusement, I had to go outside and play in a variety of locations that, thinking about it now, were a wee bit dangerous – at roadsides and riversides, in derelict buildings and old sheds, and on any roof or in any treetop I managed to climb up to. I suppose many kids in the 1970s played in places like those, but I had an advantage. I lived on a farm, which was full of machinery sheds, hay-sheds, grain stores, slurry pits, silage pits, workshops and outhouses. It was also right next to a river and a busy road. Perhaps it was this potential for injury and death in my play-area that prompted me, like most pre-pubescent males in the 1970s, to resolve that when I grew up I was going to be a film stuntman.

Accordingly, when I went fishing one day at the age of nine and fell off the riverbank, into the river, the way I recounted the mishap to my school-mates later made it sound like how Paul Newman and Robert Redford had famously jumped off the cliff and into the river in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). This feat of derring-do had actually been performed by the stuntmen Howard Curtis and Micky Gilbert. To be honest, the bank I fell off was only two feet above the water, and the water itself was only three feet deep, but in situations like these you’re allowed to use your imagination.

In fact, I became much less enamoured with action-movie stars when it occurred to me that, most of the time, they didn’t perform the breath-taking stunts featured in their films. Those were done by unsung stuntmen and stuntwomen, who therefore were the people I should admire. If I’d been on the set of Raiders of the Lost Ark in 1981, with my autograph book, I think I would have ignored Harrison Ford and made a beeline instead for stuntmen Vic Armstrong and the late Terry Richards. And that’s a big reason why I despise the 2002 James Bond film Die Another Day, which made heavy use of CGI during its action scenes. It seemed a betrayal of all the stunt-work that’d distinguished the Bond movies during their previous 40-year history and an insult to all the people who’d contributed to that stunt-work. (By my count, Armstrong and Richards both worked on six official Bond movies, and each had one ‘rogue’ 007 production to their names too – Armstrong with 1983’s Never Say Never Again, Richards with 1967’s Casino Royale.)

Anyway, here’s a list of some of my favourite stunt performers throughout history….

© Walter Wanger Productions / United Artists

Born to a US ranching family in 1895, Yakima Canutt became a world-champion rodeo rider and by 1923 was involved in the fledgling motion-picture industry, inevitably playing cowboys in westerns. However, he’d had his voice ravaged by flu during a two-year stint with the US Navy and he realised he couldn’t continue as an actor when silent films gave way to the talkies, and so he started to specialise in stunt-work. Canutt ended up as stunt double for John Wayne, who claimed to have got many of his famous cowboy mannerisms – the strut, the drawl – from him. As a cowboy, after all, Canutt was the real deal.

His most famous stunt is one he performed in 1939’s Stagecoach, in which he leaps onto a team of horses pulling the titular stagecoach, falls between them, gets dragged along and then disappears under the stagecoach itself. This inspired the sequence in Raiders of the Lost Ark where Indiana Jones is dragged beneath a German truck. Canutt later became a second-unit director and staged the chariot race in 1959’s Ben Hur. And despite sustaining injuries that required plastic surgery on at least two occasions, he lived to the ripe old age of 90.

Bud Ekins was a champion motorcyclist as well as a stuntman. It was he – not Steve McQueen, as was believed for a long time – who rode the Triumph TR6 Trophy motorbike near the end of 1963’s The Great Escape, when McQueen’s character, pursued by half the German army, attempts to leap the giant fence that separates him from Switzerland. (The famously petrol-headed McQueen did ride the motorbike during the preceding chase and was keen to perform the jump himself, but the filmmakers talked him out of it.) That alone earns Ekins a place in my Stuntmen Hall of Fame, but he went on to do lots of other cool stuff. He worked with McQueen again in Bullitt (1968), driving that film’s iconic Ford Mustang 390 GT, and he was also involved in Diamonds are Forever (1970), Race with the Devil (1975), Sorcerer (1977) and The Blues Brothers (1980).

Every time I’m on board a cable car and spot another cable car approaching from the opposite direction, I wonder if I’ll see Alf Joint perform a suicidal leap from the roof of one car onto the roof of the other – for Joint was the stuntman who doubled for Richard Burton in 1967’s Where Eagles Dare when Burton’s character had to hop cable cars close to the fearsome Schloss Adler, the mountaintop stronghold of the SS. Like many a great British stuntman, Joint’s CV is a roll-call of Bond movies (he made two), Star Wars movies (one) and Superman movies (three). He doubled for Eric Porter, playing Professor Moriarty in the acclaimed 1980s TV series The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, when the character plunged to his doom at the Reichenbach Falls; and for Lee Remick in The Omen (1976), presumably during the sequence when Remick is pushed out of a hospital window and crashes through the roof of an ambulance passing below.

© Winkast Film Productions / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

I also remember Joint performing a memorable stunt during the adverts for Cadbury’s Milk Tray chocolates, which ran on TV from 1968 to 2003 (though I hear they were revived a few years ago). These featured the Milk Tray man, a Bondian character who kept risking life and limb in order to deliver boxes of the chocolates to a beautiful lady, with the tagline being: “And all because… the lady loves Milk Tray.” I can’t recall if it was the same lady receiving all the chocolates in all the adverts – if it was, the poor woman must have developed type 2 diabetes by 2003. Anyway, Joint did the Milk Tray man’s dive off a vertiginous cliff, into a shark-infested sea, in perhaps the most famous of these adverts in 1972.

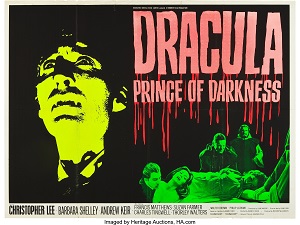

Also involved in Where Eagles Dare was Eddie Powell, a stuntman who seemed to divide his time between James Bond movies – he made ten official ones, plus Never Say Never Again – and Hammer Films, where he was a stunt double for Christopher Lee in movies like The Mummy (1959), Dracula, Prince of Darkness (1966) and To the Devil a Daughter (1976). For that last film, he also did a ‘full body burn’ stunt during a scene where satanic forces cause Anthony Valentine to spontaneously combust inside a church. In addition, Hammer gave him a few acting credits, predictably eccentric ones, such as the lumbering, bandaged monster in The Mummy’s Shroud (1967) and the half-man, half-beast Goat of Mendes conjured up at a witches’ sabbat in The Devil Rides Out (1968).

© Hammer Films / Seven Arts Productions

Later in his career, Powell performed stunts as the titular, drooling, acid-blooded, multi-mouthed beastie in Alien (1979) and Aliens (1986). For instance, he took part in the first film’s engine-room scene where the alien swoops down on the hapless Harry Dean Stanton.

Strictly speaking, I shouldn’t mention William Hobbs here as he wasn’t exactly a stuntman. He was a fight choreographer, more precisely a sword-fight choreographer, and his work enlivened many a swashbuckler over the years. He directed the swordplay in The Three Musketeers (1973) and Four Musketeers (1974) and presumably had the difficult task of restraining Oliver Reed, who from all accounts threw himself into the movies’ fight scenes with the enthusiasm of a blade-wielding Whirling Dervish. He also worked on Roman Polanski’s Macbeth (1971), Ridley Scott’s The Duellists (1977) and Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), for which he devised the samurai fights. I generally can’t stand the 1980 Dino De Laurentiis production of Flash Gordon, but the sequence where Sam Jones fights Timothy Dalton on a platform while spikes erupt at random points and at random moments through its floor, again overseen by Hobbs, is one of the film’s few good parts. Near the end of his life he was still working, on TV, arranging fights for Game of Thrones (2011-19).

Actually, you can see Hobbs in action in this instalment of the long-running TV show This is Your Life (1955-2007), rehearsing a gruelling-looking swordfight with Christopher Lee just before Eamonn Andrews surprises Lee and shepherds him off to a TV studio for a star-studded retrospective of his career. (I usually found This is Your Life tacky and maudlin, but I thought this one was fascinating because, besides Lee and Hobbs, it corrals such movie legends as Peter Cushing, Vincent Price and the afore-mentioned Oliver Reed together under one roof.)

© Troublemaker Studios / Dimension Films

And now for a lady, the New Zealand stuntwoman Zoe Bell, who doubled for Lucy Lawless in the Xena: Warrior Princess TV show and for Uma Thurman in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill movies. Kill Bill: Volume 2 (2004) involved a stunt where a shotgun blast hurled Bell backwards – this did so much damage to her ribs and wrist that she spent months recovering from it. But there were clearly no hard feelings between Bell and Tarantino because for his next movie, 2007’s Death Proof, he cast her as herself. She plays a movie stuntwoman – called Zoe Bell – who turns the tables on Kurt Russell’s car-driving serial killer. Tarantino shares my disdain for CGI and insisted that all the vehicular action seen in Death Proof was the real deal, including a ‘ship’s mast’ stunt where Bell straddles the hood of a speeding Dodge Challenger R/T with only a couple of straps to hang onto. Since then, she’s done more gigs for Tarantino, as a stuntwoman in Inglourious Basterds (2009), as an actress in Django Unchained (2012) and The Hateful Eight (2016), and as both in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019).

Finally, no roundup of my favourite stuntmen would be complete without mention of Vic Armstrong, who’s in the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s busiest stunt double. His brother Andy, his wife Wendy, and a half-dozen members of the younger generation of his family all work in the stunt / special-effects business too, which must make the Armstrongs the Corleones of the stunt-world.

As well as seven official and unofficial Bonds, his filmography includes three Indiana Joneses and three Supermen, plus a Rambo, Terminator, Omen, Conan and Mission Impossible. He served not only as Harrison Ford’s stunt double while he played Indiana Jones, but also in Blade Runner (1982), Return of the Jedi (1983), The Mosquito Coast (1986), Frantic (1988) and Patriot Games (1992). Indeed, back in his youth, his resemblance to the star was so striking that Ford once quipped to him, “If you learn to talk, I’m in deep trouble.”

© Titan Books