© Penguin Books

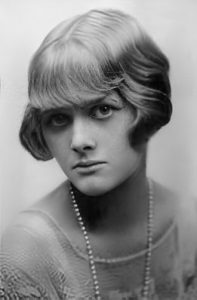

As Halloween is approaching, here’s a reposting of something I once wrote about the novella that inspired one of the greatest horror movies of all time – Daphne du Maurier’s 1971 tale Don’t Look Now, turned into the Nicolas Roeg movie of the same name two years later. And there’s mention of some other disquieting stories by her too.

I have a tiny sliver of a connection with Daphne du Maurier, the popular 20th century English writer responsible for novels like Jamaica Inn (1936) and Rebecca (1938) and short stories like The Birds (1952) and Don’t Look Now (1971). When I was at college in the 1980s, I knew her great-nephew very slightly. Actually, I was better acquainted with her great-nephew’s flatmate and a few times, because of him, I visited their apartment. Its walls were slathered with pictures of George Michael and Andrew Ridgely from the then-massive pop duo Wham, cut out of popular teen magazines of the time like Smash Hits and No 1. I assume the young du Maurier and his flatmate had stuck up these pictures in an attempt to appear ironic. Unfortunately, it meant that thereafter when I saw his great-aunt’s name on the cover of a book, I couldn’t help but hear, by way of association, the irritatingly bouncy strains of such Wham pop-dance numbers as Club Tropicana (1983) or Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go (1984).

For a long time the only thing by Daphne du Maurier I’d read was The Birds (1952), a story that because of its remote Cornish setting feels even more claustrophobic and desperate than the North America-set film version directed by Alfred Hitchcock in 1963. However, a while back, I got a chance to familiarise myself with more of her fiction when my partner gave me a copy of du Maurier’s 1971 collection Don’t Look Now and Other Stories as a present.

A novella about a grieving English couple who’re taking a break in Venice when they’re approached by two strange women – one of whom claims to be a medium – and told that their dead daughter’s spirit is trying to warn them against danger, Don’t Look Now has been filmed too. Nicolas Roeg directed a movie version in 1973 and it’s now regarded as a classic, both as a horror film and as an example of Roeg’s work in the 1970s and 1980s, which combined fragmented and elliptical narratives, haunting and recurrent images and scenes of violent and sexual intensity to unforgettable effect. Having seen the film several times over the years, I was keen to read the piece of fiction that’d inspired it.

My first impression when I started reading Don’t Look Now was that film and story felt like they belonged to different eras. The couple, John and Laura, seem more modern, liberated and chic in the film, though that may be because they were played by 1970s icons Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie. On the page, John and Laura have an old-fashioned English starchiness and they try to get over their loss with stiff upper lips and a strained Keep Calm and Carry On cheerfulness. Also, the literary John and Laura are in Venice as tourists, so they seem less confident and more vulnerable. Their cinematic equivalents are there for work reasons – John is helping to restore a Venetian church – and thus know their way around better.

Then there’s the presentation of the story. Du Maurier’s novella is a briefer and more economical account of the events I was familiar with from the film. As it stands, it could easily have been made into a 45-minute TV play. (The film clocks in at 110 minutes.) It begins in Venice with John and Laura encountering the medium. The death of their daughter, by meningitis, is mentioned retrospectively. And the suggestion that the dead girl’s spirit is urging them to leave the city before something terrible happens feels like a simple device to kick-start the main story – wherein John doesn’t leave Venice, through a series of mishaps, misunderstandings and further supernatural shenanigans; and then, when he tries to intervene in what he thinks is the mistreatment of a child, something terrible does happen.

© Casey Productions / Eldorado Films / British Lion Films

The movie opens with a harrowing sequence showing the death of John and Laura’s daughter – not by meningitis but by drowning in a pond in the English countryside. Roeg and his scriptwriters Allan Scott and Chris Bryant create a sense of a cosmic, all-encompassing evil at work. Even as the girl dies, everything that’s still to happen in Venice seems to be prefigured. We see John studying pictures of the Venetian church where he’ll be working and discovering a mysterious figure wearing a red coat in one of the slides. When he spills water onto the figure, its redness spreads across the slide like a bloodstain. John’s daughter is also wearing a red coat when she drowns and, later, so too is the child-figure John sees scarpering alongside the night-time Venetian waterways.

Indeed, in the film, John clearly makes a connection between the two characters thanks to the coat. Is the red-clad figure by the canals the ghost of his daughter? But this association doesn’t appear in the original novella.

Daphne du Maurier’s Don’t Look Now is efficiently gripping. But I think Nicolas Roeg’s brooding cinematic version, spinning a web of portents, visions and uncanny coincidences in which John’s doom seems pre-ordained from the start, is better – a work of art. That’s despite the fact that, by changing the girl’s death from meningitis to drowning, the film can be accused of illogicality. As the website British Horror Films observes pithily: “If tragedy has struck and drowned your daughter, why go to a place with an excess of water?”

Actually, with Don’t Look Now and Other Stories, I preferred a couple of those ‘other stories’ to the title one. And interestingly, nearly all of them share a similar theme, in that they deal with English people going abroad and coming unstuck as they leave their cultural comfort zones.

Not After Midnight is about an amateur artist taking a holiday in Crete to do some landscape painting. In a manner reminiscent of the hero of John Fowles’s novel The Magus (1965), he encounters a strange man and becomes embroiled in some equally-strange activities touching upon ancient Greek myths. However, while Fowles’s novel is an airy and exuberant affair where a Prospero-like figure orchestrates spectacular and elaborate ‘masques’, Not After Midnight is altogether grungier. The man putting the events in motion is a drunken, debauched brute and, accordingly, the myths invoked concern “Silenos, earth-born satyr, half-horse, half-man, who, unable to distinguish truth from falsehood, reared Dionysus, god of intoxication, as a girl in a Cretan cave, then became his drunken tutor and companion.” Du Maurier doesn’t say explicitly what bacchanalian depravities her hero finally succumbs to; but as he’s a teacher at a posh English boys’ school, we can guess.

From wikipedia.org / © The Chichester Partnership

In A Border Line Case, a young woman who works as a theatre actress tries to honour the dying wish of her father. She goes in search of her father’s long-lost best friend, to tell him that her father had wanted to “shake the old boy by the hand once more and wish him luck.” She finds the missing friend in the Republic of Ireland, living as a recluse on an island, mysteriously lording it over a cohort of local men, and engaged in activities that are probably illegal and possibly weird. Unlike the hapless protagonists in the other stories, the heroine here is a resourceful type. She uses her skills as an actress to improvise, hide her identity and talk her way out of tight spots. However, when at one point she suspects she’s stumbled across a secret society of homosexuals (“They were all homos… It was the end. She couldn’t bear it…”), you feel surprised that a theatre actress should be so wary and intolerant of gay men. Still, A Border Line Case is well-paced and balanced nicely between an adventure story and a mystery one. It builds up impressively to a nasty, if slightly predictable ending.

The book’s most humorous story is The Way of the Cross, about a group of disparate English tourists making their way to and then around Jerusalem. The characters and plot seem slightly contrived at times. It’s unlikely that a progressive left-wing lady who’s worried about the plight of the Palestinians should be married to a hard-nosed right-wing businessman. Also, a climax where two characters are stricken by unconnected illnesses and a third one suffers a serious accident stretches credibility. Nonetheless it’s an enjoyably satirical account of English folk abroad.

The final story, The Breakthrough, is the exception to the rule. Its engineer hero doesn’t leave England for another country, although he is posted to the desolate flatlands and beaches of East Anglia. There, an ambitious experiment is underway in a scientific / military laboratory, ostensibly involving computers, but really about capturing a psychic energy that surrounds people when they’re alive and escapes when they die. The Breakthrough’s blending of the scientific and the supernatural calls to mind the famously frightening TV play The Stone Tape (1973), written by Nigel Kneale. Bravely, du Maurier opts for a non-sensational ending that prioritises character over action or horror. Admittedly, some readers might find that ending a bit of a let-down.

Overall, I greatly enjoyed reading Don’t Look Now and Other Stories, because of the author’s precise and no-nonsense prose, her ability to pack a lot of incident into her narratives without letting them get too convoluted, and her determination at all times to tell a rattling good yarn.

Indeed, on the strength of this, I’m now starting to think of Daphne du Maurier as being in the mould of Stephen King – and not so much in connection with George Michael and Andrew Ridgely. Yes, better the author of The Running Man (1982) than the authors of I’m your Man (1986).

© Casey Productions / Eldorado Films / British Lion Films

Expect more on Daphne du Maurier very soon…