From unsplash.com / © Reyk Odinson

Donald Trump has recently rampaged through the world’s global trade system with the delicacy of Godzilla taking a stomp around downtown Tokyo. That would be Godzilla after he’d been on a week-long cocaine binge. So, in the current climate of gloom, dread and despondency, perhaps it’s unsurprising that the world’s news outlets have latched desperately and uncritically onto a story that looks like good, even uplifting, news. Those news outlets have made much of the claim by an American biotechnology and genetic engineering company called Colossal Biosciences that it’s created the first dire wolves to have graced Planet Earth in about ten millennia.

The dire wolf, according to Wikipedia, is “an extinct species of canine which was native to the Americas during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene epochs (125,000-10,000 years ago).” It was generally bigger than most modern wolves. Research suggests “the average dire wolf to be similar in size to the largest modern grey wolf.” Dire wolves also pop up in George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones books (1991-2011), but more about that in a minute.

The headlines have come fast and furious: DIRE WOLF REPORTEDLY BROUGHT BACK FROM EXTINCTION; NO LONGER EXTINCT: DIRE WOLVES HOWL AGAIN AFTER 12,000 YEARS; LONG EXTINCT, DIRE WOLVES ARE BACK, AND NOT JUST IN GAME OF THRONES; SCIENTISTS PERFORM WORLD’S FIRST DE-EXTINCTION TO REVIVE THE DIRE WOLF THAT VANISHED 12,000 YEARS AGO. Time Magazine stuck a picture of one of three dire wolves supposedly created by Colossal Biosciences on a recent cover, below the word ‘extinct’ with a line scored through it and the inspiring message: “This is Remus. He’s a dire wolf. The first to exist in over 10,000 years. Endangered species could be changed forever.”

So hey, this is great news, yeah? Extinction is bad, so ‘de-extinction’ must be good, right? And since much extinction in the last couple of millennia had been caused by humanity, isn’t it gratifying to see good old human know-how being put to work reversing the process and bringing one – hopefully the first of many – extinct species back?

Except, of course, that it’s a load of bollocks. The New Scientist has responded to the company’s claims with an article whose lead-in puts it succinctly: “Colossal Biosciences claims three pups born recently are dire wolves, but they are actually grey wolves with genetic edits intended to make them resemble the lost species.” Although some genuine dire-wolf DNA was used in the project, the genome was merely analysed to determine what a dire wolf’s key traits would be. The DNA itself was way too aged and decayed to be spliced into anything, Jurassic Park-style. The Colossal Biosciences team then made edits to modern-day grey-wolf DNA to replicate those dire-wolf traits. Finally, three modified wolf-pups were produced using domestic-dog surrogate mothers and caesarean sections. So what you’ve got aren’t dire wolves. You’ve got three grey-wolf pups that’ve been tinkered with genetically to give them characteristics the team think dire wolves might have had.

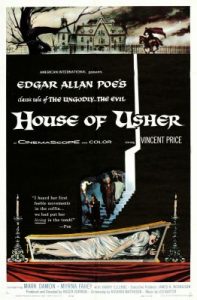

The analogy here isn’t the Steven Spielberg movie Jurassic Park (1993). No, it’s Irwin Allen’s terrible 1960 adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912) starring Claude Rains, Michael Rennie, David Hedison and Jill St John. In that film, the dinosaur special effects were achieved by taking modern reptiles like iguanas, monitor lizards and crocodiles and glueing horns, frills and fins onto them to make look ‘dinosaur-ish’. Which is what’s been done with these young grey wolves in a fancy, high-tech way.

The Irish-American palaeontologist and writer Caitlin R. Kiernan summed it up bluntly in her online journal the other day: “…there’s this bullshit about a company named Colossal Biosciences claiming to have resurrected dire wolves. They haven’t. Not even close. It’s a hoax that would make P.T. Barnum proud.”

From wikipedia.org / © American Museum of Natural History

Also, it’s not merely nonsense, but dangerous nonsense. It makes extinction sound like something that’s solvable through scientific jiggery-pokery, an error that can be fixed without the arduous, inconvenient lengths that human beings need to go to to prevent extinctions happening, which is to stop killing life-forms through hunting, habitat-destruction, economic consumption and general greed, cruelty and ignorance.

In the last few days alone, I’ve seen stories on the Guardian’s environment page about a report on New Zealand’s environment, which warns that “76% of freshwater fish, 68% of freshwater birds, 78% of terrestrial birds, 93% of frogs, and 94% of reptiles” are “threatened with extinction or at risk of becoming threatened”; and a warning by 32 charity organisations that proposals under the British government’s new planning bill “could push species towards extinction and lead to irreversible loss”; and the grim likelihood that Donald Trump’s decimation of USAID will wreck conservation projects leading to increased poaching and habitat encroachment and serious threats to such animals as lemurs, white rhinos, gorillas, orangutans and elephants.

The uncritical coverage given to the dire-wolf story is harmful because it encourages the idea that animal extinction is not so serious now because science can resurrect those animals later. Which would be bad enough if the idea was based on proper science. But it’s not – it’s based on the spin coming out of Colossal Biosciences.

As I said, direwolves (spelt not as two but as one word) turn up in the Game of Thrones books: “Direwolves once roamed the north in large packs… According to Theon Greyjoy, direwolves have not been sighted south of the Wall for two hundred years. Rangers of the Night’s Watch hear direwolves beyond the Wall.” I’m quoting a Game of Thrones wiki here, as I’ve never read the books. I haven’t watched the 2011-2019 TV show based on them either, having always intended to read the books first.

I find it a bit disappointing that Games of Thrones author George R.R. Martin seems to have swallowed the Colossal Biosciences hype hook, line and sinker. In a recent blogpost, he said in February he’d been to visit the secret installation where the three supposed direwolves are being kept. Obviously in a state of giddy excitement, he declared: “I have to say the rebirth of the direwolf has stirred me as no scientific news has since Neil Armstrong walked on the moon… And Colossal is just beginning. Still to come, the woolly mammoth, the Tasmanian tiger, and… yes… the dodo… I can’t wait.” The post also has an undeniably cute picture of him holding one of the genetically-edited beasties.

To be fair to Martin, I suppose it must be flattering to have a biotech company pay you the compliment of (allegedly) creating some animals that nowadays most people only know as fantasy-creatures in your novels. So flattering that it’s befuddled his critical faculties. Of course, it’s likely that Colossal Biosciences chose to work on dire wolves because the creatures are currently famous due to the Game of Thrones phenomenon – making it an excellent PR stunt that’s earned them lots of headlines.

And I suppose, as someone who writes fantasy fiction under the penname Rab Foster, I’d be flattered too if a biotech company offered to create some fabulous animals or monsters that’d appeared in my stories. Not that there’s much chance of that happening – last year, as Rab Foster, I earned about 75 pounds, which I suspect is a wee bit less than George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones royalties for 2024. If any biotech outfit was up for it, though, I’d like them to have a go at creating the sinister miniature-harpy things in my 2022 short story Crows of the Mynchmoor, which were basically crows’ bodies with shrunken copies of a witch’s head grafted onto then. I’d like a flock of those to keep in my garden. I bet they’d really creep out folk passing by on the street.

© 20th Century Fox