One week before November 22nd, the evening I went to see Welsh rock band the Manic Street Preachers perform at Singapore’s Star Theatre, I read John Niven’s satirical 2018 novel Kill ‘Em All.

Kill ‘Em All is a sequel to Niven’s Kill Your Friends, written a decade earlier. It continues the adventures of Steven Stelfox, a record-company A&R agent so devoid of things like conscience, empathy or decency, and so determined to climb the corporate ladder and make pots of money, that he’ll countenance doing anything, murder included. In Kill ‘Em All, Stelfox has become a millionaire through helming a hit reality TV show called American Pop Star – I wonder if Niven had a real person in mind when he constructed that scenario? – and the immoral, money-grasping monster has taken to the late 2010s, the era of President Donald Trump, like the proverbial pig to shit. He’s particularly enamoured with the phenomena of fake news, online conspiracy theories, social-media rabbit-holes, and bot-farm-generated misinformation and propaganda, which the Trump presidency elevated to a new level. At one point, referencing the title of the Manic Street Preachers’ 1998 album, he sneers: “This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours, those Welsh socialist miner f**ks sang, way back in the day, before all of this happened. Nowadays? This Is My Lie Prove Me Wrong.”

That wasn’t the only coincidence I experienced with the November 22nd show. I’ll explain the other coincidence later.

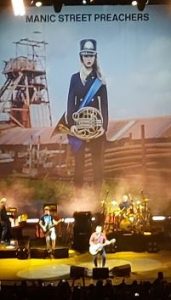

Anyway, the backdrop for the Manic Street Preachers’ gig in the plush, sweeping amphitheatre of the Star Theatre seemed in defiance of Stellfox and the rapacious, corporate world he represents. It was a reproduction of the cover for their 2011 compilation album National Treasures – the Complete Singles, depicting a girl clutching a French horn, clad in a brass-band uniform (presumably a colliery band) and standing in front of a pithead (presumably a Welsh one). Reassuringly, this suggested the Manics – who in 2000 released a single called The Masses against the Classes (2000), which begins with a quote by Noam Chomsky and has the Cuban flag on its sleeve – remained proud ‘Welsh socialist miner f**ks’.

© Columbia

Nonetheless, I felt apprehensive about what lay ahead of me. I’d only seen the band once before, in 1993, when they were promoting their album Gold Against the Soul. They turned up in the Japanese city of Sapporo, where I’d recently started a job, and delivered one of the most memorable live-music shows I’d ever attended. It was also rather odd. In Britain they might have had a reputation for being radical, shit-stirring retro-punks, but in Japan they were seen as a sort of Guns n’ Roses-lite, possibly thanks to their predilection for wearing eye-liner and slightly glam clothes. Accordingly, their gig at Sapporo’s Penny Lane attracted a squad of young Japanese ladies dressed in floppy hats and silk scarves who spent their time squealing ‘Rich-ee!’ at the band’s iconic but troubled guitarist, Richey Edwards. Tragically, Edwards was to disappear, and never be seen again, two years later.

That 1993 gig was emblematic for me. The young Manic Street Preachers had throbbed onstage with a brash, youthful energy that mirrored how I felt too at the time – I was young, full of beans, ready to take on the world. And later, looking back, the memory of it made me feel a little melancholic in a wistful, where-did-my-youth-go? sort of way. This was emphasised by something that happened a decade afterwards. I listened to my copy of Gold Against the Soul, which I’d bought in Japan, for the first time in ages. It was only then that I discovered the bulky CD case contained a second tray I hadn’t noticed before. This tray held a second, bonus CD – a live one of them performing during their 1993 Japan tour. I played it and immediately felt a nostalgic sadness, for in the crowd I could hear those ladies shouting “Rich-ee!” again at the Manics’ now-vanished guitarist. It wasn’t so much a CD as a time capsule.

So, how would the band strike me in 2023, now that they and I were well into our middle-age? And in the Star Theatre, a venue that seemed the antithesis of the small, intimate and cheerfully dingy place that Penny Lane had been? (One major point of difference between them was the purchasing of alcohol. In Penny Lane you got tins of Sapporo beer out of a cheapish vending machine at the back of the little auditorium. At the Star, where your bags were painstakingly checked before you entered the premises to ensure you weren’t bringing in any food or drink – not even water – you joined a long queue for the privilege of buying a pint of beer for 24 Singaporean dollars, which is about 14 British pounds. Phew. Steven Stelfox could have been running the catering.)

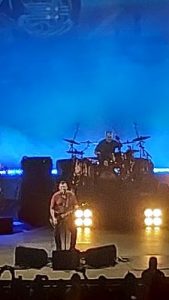

But enough of the brooding introspection. The Manics came onstage just after half-past-seven and launched into Motorcycle Emptiness, from their first album, Generation Terrorists (1992). And undeniably, they sounded good. They didn’t show the raw, sometimes-nervous, sometimes-ragged energy that they’d shown in 1993, but played with the confidence and professionalism you’d expect from an outfit who’ve been together for more than three decades.

Yet it wasn’t the slick, on-autopilot, by-the-numbers performance of a jaded old rock band. The Manics retained their pleasing idiosyncrasies of old. Sporting a white dress-jacket and (for a bloke his age) an astonishingly skinny pair of jeans, tall, gangling bassist Nicky Wire still looked like he’d been assembled out of pipe cleaners – and still ambled about like a man with a new pair of legs who was testing out what they could do. Meanwhile, vocalist / guitarist James Dean Bradfield, during those moments when he let himself go, behaved like a dad secretly dancing to his favourite music in his bedroom, twirling around, pogoing on one leg, attempting a Chuck-Berry-style duck-walk.

When the Manics had played Penny Lane in 1993, their set had consisted entirely of numbers from Generation Terrorists and Gold Against the Soul, the only albums they’d released by then, so tonight I was treated to much broader palette of music. There were five songs from Generation Terrorists: Little Baby Nothing, Slash ‘n’ Burn, Stay Beautiful and You Love Us, as well as Motorcycle Emptiness. Wire dedicated Stay Beautiful to the memory of Richey Edwards. From Gold Against the Soul – an album that, despite me really liking it, has never been highly regarded in the Manics’ oeuvre – only From Despair to Where got an airing. From the late 1990s, when the band were perhaps at their commercial and critical peak, they played A Design for Life, Everything Must Go, Australia (all 1996), If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next and You Stole the Sun from My Heart (both 1998), while the band’s 21st-century career was represented by a smattering of singles like Your Love Alone is Not Enough (2007), Walk Me to the Bridge (2014) and International Blue (2018).

Thus, it was almost a greatest-hit package, which went down well with the audience. Many of them seemed to be long-term fans. Despite the constraints of the Star Theatre, with its wall-to-wall seating, a lot of folk were soon on their feet, jumping about as if they were in an open venue. Two big, macho-looking guys a few rows in front of me, obviously well refreshed, got extremely emotional – arms wrapped around each other, bodies swaying precipitously from side to side. If the gig had lasted another half-hour, they’d probably have shagged each other in public. I even thought I heard a distant, communal chant of “Wales! Wales! Wales!’ at one moment. (In addition to the backdrop’s picture of a Welsh colliery, a Welsh flag was draped over one of the units behind the band, and Bradfield and Wire mentioned their home country several times during their between-songs banter.)

Most bands who are still recording would pepper their set-list with ‘new songs’ off the ‘new album’. But the Manics trotted out only one number from their most recent offering, 2021’s The Ultra Vivid Lament, an album I’d never heard and knew nothing about. I was really surprised, then, when the song they played from it turned out to be called Still Snowing in Sapporo. Later, when I researched the song, I discovered that it’d been inspired by the concert they’d done in Sapporo 30 years ago – the one I’d attended. According to songfacts.com: “When the Manic Street Preachers toured Japan in 1993 they played a gig there. The song is a reverie of a magic moment, when they felt they could pretty much do anything.” Wow! That was how I’d felt about myself, that I could do anything, when I saw them. And how weird to hear them perform a song inspired by a long-ago gig and realise I was (probably) the only person in the audience who’d been at that long-ago gig.

So, now, I feel more psychically attuned to the band than ever… Strictly speaking, though, the Manics’ Sapporo concert was on October 22nd, 1993, which makes the song-title Snow Falling on Sapporo redundant. Snow wouldn’t have started falling on the city yet. But I’ll allow them poetic licence.

When the band finally trooped off the stage, they left behind an extremely satisfied crowd. A man beside me remarked, “Suede will have to be bloody good to top that.”

Oh. Did I say Suede were playing on the bill too? Well, they were. But that’ll be the subject of another blog-post.