© American International Pictures

Following on from my last blog-post, in which I paid tribute to the prolific, indefatigable and – it has to be said – thrifty filmmaker Roger Corman who died on May 9th, here’s a round-up of my favourite films that Corman directed.

A Bucket of Blood (1959)

Character actor Dick Miller worked regularly with Roger Corman. His biggest role for him was in a movie that’s also Corman’s best work of the 1950s, the horror-comedy A Bucket of Blood. Miller plays a would-be avant-garde sculptor called Walter Paisley who’s increasingly frustrated at his lack of talent. This isn’t helped by the fact that, to make ends meet, he has to work as a busboy at the local Beatnik café, which is full of pretentious tossers going on about what creative geniuses they are. “Be a nose! Be a nose!” the hapless Paisley cries as he tries and fails to fashion a recognisable human visage out of a lump of clay. After accidentally killing his landlady’s cat and then killing an undercover cop who’s trying to implicate him in some drug-dealing at the café (Paisley memorably cleaves his head with a skillet), he hits on a way of producing perfectly proportioned statues: committing murder and coating the bodies in clay. Frankly, the resulting corpse-statues look hideous, but that doesn’t stop the Beatniks at the café proclaiming Paisley an artistic genius.

Their lack of taste in sculpture mirrors their lack of taste in poetry. At the beginning we hear Beatnik bard Maxwell Brock (Julian Burton) delivering an epic, and epicly bad, poem called Life is a Bum, which goes: “Life is an obscure hobo bumming a ride on the omnibus of art… The Artist is, all others are not… Where are John, Joe, Jake, Jim, Jerk? Dead, dead, dead! They were not born before they were born, they were not born… Where are Leonardo, Rembrandt, Ludwig? Alive, alive, alive! They were born…!”

© Alta Vista Productions / American International Pictures

The Raven (1963)

As a kid, I loved this movie, the fifth of Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations for American International Pictures. The tale of a trio of feuding magicians played by Vincent Price, Boris Karloff and Peter Lorre, it’s more fantasy than horror – but spiced with delightfully ghoulish moments, such as when a torturer checks the temperature of a red-hot poker by pressing it into his own arm, or when Price opens a little casket and is discombobulated to find it full of human eyeballs. (“I’d rather not say,” he croaks when Lorre asks him what’s inside.) It’s like a version of Walt Disney’s Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971) for morbid children.

Needless to say, the film’s connection with Edgar Allan Poe is extremely loose. In fact, it’s only Karloff turning Lorre into a raven twice during the film that allows Corman to tack the title of Poe’s most famous poem onto it and have Price recite the poem mellifluously during its opening scene. Meanwhile, in the role of Lorre’s son, we get a 26-year-old and amusingly wooden Jack Nicholson.

© Alta Vista Productions / American International Pictures

X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963)

A non-gothic movie Corman made whilst in the middle of his Edgar Allan Poe cycle, the sci-fi chiller X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963) is about a scientist, played by Ray Milland, who experiments on his own eyes and ends up seeing beyond the usual visual spectrum perceptible to humans.

I wrote about this movie last year in a post about its scriptwriter, Ray Russell. “Milland’s increasingly penetrative vision goes from letting him see though clothing – hence a party scene where, to his bemusement, the dancing revellers appear to be cavorting in the nude – to letting him see the distance edges of the universe, where horrible things lurk. How one reacts to the film today depends on how one reacts to the special effects that Corman, a famously thrifty filmmaker, deploys to represent Milland’s visions. They vary from psychedelic patterns and filters to (when he’s peering into human bodies) flashes of what are obviously photos and diagrams taken from human-anatomy manuals. The effects are either desperately ingenious or just plain desperate, depending on your attitude. Still, the film cultivates an effective mood of cosmic horror and the ending is nightmarish in its logic.”

The Masque of the Red Death (1964)

Corman’s majestic adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death, scripted by Charles Beaumont and R. Wright Campbell (with a second Poe story, Hop Frog, stitched into the plot for good measure) and beautifully shot by the great Nicolas Roeg, showcases Vincent Price at his sumptuously evil best. He’s Prince Prospero, who’s holed up in his castle with an entourage of loathsome aristocrats while a plague, the Red Death, decimates the countryside outside. Price and friends happily live a life of decadence, fuelled by drink, drugs, sex and diabolism – rather like Boris Johnson and his lackeys and minions partying at No 10, Downing Street, during Covid-19 and breaking all their own lockdown restrictions – while refusing to help the neighbourhood’s terrified peasants. However, when they decide to enliven their social calendar with a fancy-dress masque, the masque is gate-crashed by a mysterious, Ingmar Bergman-esque figure swathed in a red robe. Guess who that is.

© Alta Vista Productions / Anglo-Amalgamated / Warner Pathé

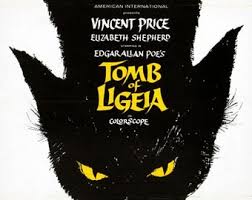

Tomb of Ligeia (1964)

Made the same year as Masque, Corman’s Ligeia has Price in a more sympathetic role, playing a haunted and reclusive man who tries to put his troubles behind him and find happiness with a new wife (Elizabeth Shepherd). Unfortunately, his former wife, though dead, is still around in spirit form and won’t leave him in peace. Tomb of Ligeia has a slightly over-the-top ending, but the build-up to it, involving black cats, flag-stoned passageways, cobwebs, candlelight, hypnosis, Egyptology and some spectacular monasterial ruins filmed at Castle Acre Priory near Swaffham in England’s County Suffolk, is spookily wonderful.

The Wild Angels (1966)

“Just what is it that you want to do…?” “Well, we wanna be free, we wanna to be free to do what we wanna do. And we wanna get loaded and we wanna have a good time. And that’s what we’re gonna do…. We’re gonna have a good time, we’re gonna have a party!”

Scottish alternative rock / dance band Primal Scream immortalised this exchange from Corman’s The Wild Angels, between Frank Maxwell’s preacher and Peter Fonda’s Hells Angel, by sampling it on their 1990 dancefloor hit Loaded. Though to be fair, the American grunge band Mudhoney got there first when they sampled it on their song In and Out of Grace two years earlier. It’s also recited at the climax of The World’s End, Edgar Wright’s underrated sci-fi / horror satire from 2013, during the face-off between Simon Pegg and a supercilious alien intelligence voiced by Bill Nighy.

In addition to Fonda, The Wild Angels features Nancy Sinatra, Bruce Dern, Diane Ladd – supposedly Dern and Ladd’s daughter Laura was conceived during filming, so Laura Dern is something else we have Roger Corman to thank for – and the baby-faced Michael J. Pollard shortly before he played W.C. Moss in Bonnie and Clyde (1967). The script, officially written by long-term Corman associate Charles B. Griffith and unofficially rewritten by Peter Bogdanovich, is minimalist. While there’s stuff about Fonda’s Hells Angels chapter pursuing a stolen bike, and about Dern’s character being shot by the cops and having to be rescued from a hospital, it’s mainly a frame for scenes in which the Angels offend Middle America. Corman did his research by throwing parties with free beer and marijuana for real Hells Angels. He had Griffith attend them and make notes while those Angels recounted their wild (and no doubt exaggerated) tales of life on the road.

© American International Pictures

At least Griffith and Bogdanovich don’t pull their punches. In the script, the Angels come across as pretty assholey, particularly with their love for Nazi symbols and memorabilia. This causes a confrontation between them and a World-War-II veteran (Dick Miller again) early in the movie. When Dern’s character dies and they organise a funeral for him – predictably, the church service degenerates into an orgy – the coffin is draped in a Nazi flag. The real Hells Angels, some of whom had appeared in the film, were so annoyed by Corman’s portrayal of them that they threatened to both kill him and sue him (presumably not in that order). If that wasn’t enough, Corman had Frank ‘Dodgy Connections’ Sinatra breathing down his neck, concerned about daughter Nancy’s safety among the Angels on the set. Actually, the story of an exploitation director making a biker movie who unwittingly antagonises the Hells Angels and the Mafia sounds like it would make a good exploitation movie.

The Trip (1967)

Corman, Fonda and Dern were united for this movie, scripted by one Jack Nicholson. Yes, it’s about a trip, a hallucinogenic one, experienced by a TV commercial director played by Fonda, wearing a sensible red V-necked sweater. He takes LSD as a reaction to the break-up of his marriage and the trip initially happens at the home of, and under the watchful eye of, a friend played by Dern, wearing a sensible eggshell-blue polo-neck and fawn jacket. These scenes were filmed in the house of Albert Lee, leader of the rock band Love. The cost-conscious Corman was surely pleased to discover that Lee’s house had so much psychedelic décor already it hardly needed to be dressed up for the film. However, when Fonda hallucinates that he’s killed Dern – he hasn’t – he panics and flees down to Sunset Strip. Then things really get groovy.

Seen today, The Trip is inevitably something of a museum piece and the low budget means some of its fantasy scenes are ropey. Bits where Fonda, now wearing a baggy white shirt like a romantic poet, is pursued by medieval, cloaked-and-cowled figures on horseback through what is obviously modern-day California are particularly cringey. But there are enough genuinely weird things – Fonda having a question-and-answer session with Dennis Hopper on a carousel, Fonda making love to a lady under some heavily patterned lighting that makes them look like psychedelically-coloured chameleons, Fonda having a panic attack inside Dern’s wardrobe – to make it memorable. And if you enjoy a good 1960s-movie psych-out sequence, the one where the heavily-tripping Fonda blunders into a night club during a live rock performance is awesome.

© American International Pictures

Bloody Mama (1970)

Like The Wild Angels, this Corman movie isn’t so much a story as a series of outrages, with reprobates lurching from one confrontation to another. Unlike The Wild Angels, the characters in Bloody Mama are based, very loosely, on historical figures – Depression-era America’s notorious Barker-Karpis Gang, supposedly led by matriarch Kate ‘Ma’ Barker. Many have argued that Ma Barker’s reputation as a criminal mastermind was invented by the media and by J. Edgar Hoover, keen to justify the FBI killing an old woman when they finally caught up with her and shot her. As the fictionalised Ma Barker, lording it over her four gormless gangster sons, Shelley Winters gives a scenery-chomping performance that dominates the film and blinds you to its various budgetary and exploitative shortcomings. God-fearing, gun-toting, racist, incestuous and psychotic, she seems a monstrous metaphor for America itself. This is underlined when she herds her sons around the piano to sing Battle Hymn of the Republic.

Among the sons, Don Stroud gets most to do as Ma’s eldest, Herman. He’s a hulking thug to begin with but, in some unexpected character development, gradually forms a mind of his own. Film buffs, though, will be more excited by the presence of a young Robert De Niro, playing well-medicated son Lloyd. At one point he gets high on glue, causing an uncomprehending Winters to exclaim, “When you’re working on those model airplanes, you get to acting awful silly!”

Incidentally, Bloody Mama was such a money spinner for American International Pictures that they demanded another Depression-era gangster movie. Corman, though, was willing only to produce the follow-up, Boxcar Bertha (1972), and a young lad called Martin Scorsese got the directing gig.

When I first started writing this tribute to Roger Corman, I was going to title it THE MAN WHO ROGERED HOLLYWOOD, though I soon decided that sounded disrespectful. But Corman literally did roger Hollywood. Without his opportunities and tutelage, Coppola, Scorsese, Cameron, Nicholson, etc., might never have got to where they did, and many landmark movies during the last half-century of Hollywood’s history – from the Godfather movies to the Scorsese-De Niro collaborations, from the Terminator and Avatar series to a host of classic films including Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Joe Dante’s Gremlins (1984), Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs (1989), Carl Franklin’s One False Move (1993) and Curtis Hanson’s LA Confidential (1997) – might not have seen the light of day. And many of his own movies, cheap though they were, were a great deal of fun. No wonder Quentin Tarantino loved him.

Not bad for the guy who directed It Conquered the World (1956) and produced Dinocroc vs Supergator (2010).

© Alta Vista Productions / American International Pictures