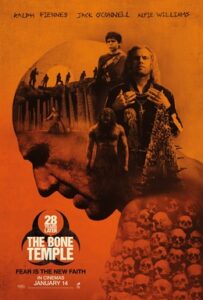

© Columbia Pictures

The recently released 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple is the latest in the series of British zombie movies that began with 28 Days Later (2002). It’s also a direct sequel to last year’s 28 Years Later. Though I had a few reservations about 28 Years Later, which was scripted by Alex Garland and directed by Danny Boyle, creators of the original 2002 film, it generally impressed me. I felt wary about the forthcoming Bone Temple, though, because one of my 28 Years Later reservations was how it ended and set up its sequel.

I wrote at the time: “Its last minutes have upset a few people with their unexpected reference to a dark episode in recent British history, but I don’t mind that. I think it’s a pretty audacious move by Garland’s script. Rather, I don’t appreciate the goofy, cartoony manner in which those last minutes are filmed, which jar against the sombre tone of everything that’s happened previously. This makes me nervous about what the sequel will be like (and it isn’t directed by Boyle, but by Nia DaCosta).”

Happily, having just seen 28 Year Later: The Bone Temple, I realise I had nothing to worry about. It isn’t goofy or cartoony at all. Actually, Nia DaCosta shoots her movie in a more measured, controlled style than Boyle shot his – he filmed with numerous iPhone cameras, edited frenziedly, and intercut the action with clips from old war documentaries and Laurence Olivier’s Henry V (1944). Parts of DaCosta’s film are so still and character-focused you feel you’re watching a stage-play. And overall, it’s a near-perfect blend of horror, violence, humour, pathos and, yes, optimism. I’d even rate it as the best of the 28 Days / Weeks / Years Later movies – praise indeed, since I think the previous three films are all quality. (I know the 2007 installment, Juan Carlos Fresnadillo’s 28 Weeks Later, gets some grief. But, apart from one idiotic lapse in plot logic, I like it.)

A warning. From here on, there’ll be spoilers for 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple.

So, what was that ‘dark episode in recent British history’ referenced at the end of 28 Years Later? Well, it concluded with its juvenile hero Spike (Alfie Wiliams) being rescued from the infected – the series’ name for the humans who’ve succumbed to the ‘rage virus’ and transformed into slavering, red-eyed, hyperactive zombies – by eight youths wearing tracksuits, bling and long, blonde wigs. Their leader, played by Jack O’Connell, introduces himself as ‘Sir Jimmy’. Indeed, they’re all called ‘Jimmy’: Jimmy Shite, Jimmy Fox, Jimmy Snake, etc. Wandering around this post-apocalyptic, zombie-infested hellscape is a gang fixated on Jimmy Savile.

At this point, British viewers of 28 Years Later went, “Eek!” Everyone else in the world probably went, “Huh?”

Savile, in case you didn’t know, was a British disc jockey, children’s TV presenter and charity fundraiser – in his lifetime he raised around 40 million pounds – who died in 2011. With his long, greasy locks of blonde hair, penchant for tracksuits, cigars and bling, and irritating, homemade patois (“Now then, now then, as it happens, goodness gracious, how’s about that then, guys ‘n’ gals?”), he cut a grotesque figure, but was regarded as a saint because of his charity work. One year after his death, though, he turned into a modern-day folk-demon when it became apparent he’d been a sexual predator who’d abused children, young women and others on an industrial scale – often patients in hospitals he’d raised funds for. In fact, there’d been rumours about his evil proclivities while he was alive, but he never faced justice thanks to his saintly image and connections with the political and media establishments.

© Columbia Pictures

28 Years Later began with a prologue, seemingly unlinked to the rest of the film, wherein during the rage virus’s original outbreak in 2002 a group of children are stuck in a room watching a Teletubbies (1997-2001) video while their parents try, unsuccessfully, to barricade the house against an army of the infected. Only one small boy escapes and he flees into a nearby church. There, he sees his father, the local cleric, get attacked, transform and then seemingly lead the other infected off in a macabre, marauding dance. The boy, it transpires, becomes Sir Jimmy, O’Connell’s character. Grown up, his brain is an unhinged cocktail of zombie trauma, garbled religious dogma (from his father) and obsolete British pop culture (from the TV) – in the films’ alternative timeline, civilization ended in 2002, so Savile’s crimes were never revealed. Thus, Sir Jimmy enthuses about Teletubbies and has trained one of his gang, Jimmima (Emma Laird), to do a Teletubbies dance-routine. Also, echoing Savile, he frequently talks about ‘charity’ – though he uses the word as a euphemism for ‘torture’.

For Sir Jimmy’s gang are Clockwork Orange-type psychopaths. He’s convinced them he’s the son of the devil and they’re on a holy, or unholy, mission to slaughter the infected and uninfected alike in what’s left of Britain. Spike, fallen into their clutches and forced to join their ranks, spends 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple trying to stay alive and figure out how to escape from them.

The movie has a second plot-strand, concerning Dr Ian Kelson (Ralph Fiennes), whom we also met in the previous film. He’s a hermit who, in the middle of the countryside, has created a spectacular ‘bone temple’ – a structure built from the skeletal remains of the victims of the 28-year-long contagion that also honours those victims. Kelson is certainly eccentric, but he’s decent and humane too and he’s managed to find a way of peacefully co-existing with the dangerous, brutal world around him.

Emblematic of that danger and brutality is Samson (Chi Lewis-Parry) – the name Kelson has given an ‘alpha’ member of the infected who stalks the environs of the temple. Alphas are specimens bigger, stronger and even more dangerous than the ordinary infected. Kelson uses morphine-tipped darts fired from a blowpipe to subdue Samson as he approaches, but he’s noticed that Samson has been coming back to the temple more often. It’s as if he enjoys the doses of morphine he’s getting. This inspires Kelson to experiment on the alpha. How much, he wonders, of what’s wrong with the infected is a virus and how much is psychosis? If the psychosis can be calmed – possibly lifted? – by drugs, what remains of the victim’s mind and memories? Though Spike’s dad (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) claimed in the previous film that the infected don’t have souls, Kelson, as his relationship with Samson develops, realises something of a soul does linger in the infected’s simultaneously terrifying and pitiful husks.

So, Spike is trapped among the Jimmies, Fiennes is improbably bonding with Samson and, ominously, we know these two storylines are going to crash together sooner or later with painful results for everyone. One thing I like about The Bone Temple, again scripted by Alex Garland, is that for all the simplicity of its plotting, it’s less predictable than you’d expect. I’d assumed the Jimmies would intrude violently on Kelson with a ‘home invasion’ of his bone temple, but what happens is more complex. I’d also seen people assume online before the film’s release that the Jimmies would kill Kelson and an enraged Samson would go on the rampage, or the Jimmies would kill Samson and an enraged Kelson would go on the rampage – but neither happens here. The real outcome is unexpectedly hopeful, funny, sad and satisfying. And the long-awaited scene when Sir Jimmy and Kelson finally come face to face is splendid in both its drama and its restraint. Generally, while O’Connell’s performance is great, Fiennes’ performance is one for the ages.

The previous film posited that although Britain had been ravaged by the rage virus, mainland Europe hadn’t and it’d continued to develop as it actually did in the 21st century. This scenario of an isolated and seriously in-the-shit Britain was an obvious metaphor for Brexit. The Bone Temple is less on the nose with state-of-the-nation metaphors, but you can still see some.

The kids making up Sir Jimmy’s gang – and they are kids, as evidenced by scenes where a couple of them suffer fatal injuries and reveal their true, frightened selves during their death throes, one of them even lamenting about a long-ago pet kitten – symbolize the victims of a half-century of ruthless government policies that decreed there had to be winners and losers and split the country into haves and have-nots. They’re the losers, the have-nots, the left-behind youngsters condemned to membership of a feral underclass. Tellingly, the opening scene shows the Jimmies gathered in a decayed public swimming pool in some abandoned post-industrial city: the sort of public amenity, in the sort of place that desperately needed public amenities, that got the chop during David Cameron’s premiership and ‘austerity’ project in the early 2010s.

Significantly, they’re exploited, manipulated and fashioned into a squad of killers by someone modelling himself on Jimmy Savile. The real Savile was a respected member of the establishment at the time when British politics turned callous and abandoned the principle that all citizens, including the weak, poor and vulnerable, should be looked after. Each Christmas-time in the 1980s, for instance, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher would invite him to spend Boxing Day with her at Chequers. He was also a confidante of Prince (now King) Charles.

© Columbia Pictures

If Sir Jimmy and his minions represent everything rotten about Britain recently, Kelson represents the opposite. For one thing, he was formerly a doctor in the country’s National Health Service, an institution founded on the principle that the weak, poor and vulnerable should be looked after (and not have to pay a fortune for their treatment). When he treats the arrow wounds that a doped-up Samson has incurred during his travels, he quips, “So you owe me… Only kidding. I’m NHS, free of charge.” Another British cultural reference that may go over the heads of American audiences.

Kelson also reminds us that as well as being an imperial superpower, Britain was once a more benevolent, cultural one. (It helps that he’s played by Ralph Fiennes, a fixture in two massive, British-originating cultural franchises, Harry Potter and James Bond.) Despite the apocalypse, Kelson has managed to hang onto his old vinyl collection and he plays stuff from it at appropriate moments – Duran Duran’s Ordinary World (1992) when Samson needs some pacification; Radiohead’s Everything in its Right Place (2000) when he’s wistfully contemplating the night-sky; and fabulously, when he has to deal with the Jimmies, Iron Maiden’s Number of the Beast (1982) – “Let’s turn this up to 11,” he says, and he does. Iron Maiden, Radiohead, Duran Duran… In their different ways, at different times, these British bands were massively popular, musical juggernauts worldwide (and coincidentally, all three have been touring again lately). That’s the sort of global soft power Britain should be proud of.

Indeed, Kelson seems an embodiment of the caring and creative British values that the country tried to project to the outside world during the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics – a ceremony whose artistic director was Danny Boyle.

Aside from the script, performances, themes and general execution, a reason why I liked The Bone Temple so much was because the relationship between Kelson and Samson echoed something in one of my all-time favourite horror movies, George A. Romero’s Day of the Dead (1985). In the Romero film, a scientist called Dr Logan (Richard Liberty) attempts to ‘domesticate’ a zombie nicknamed ‘Bub’ (Sherman Howard). Good though Chi Lewis-Parry is, Samson doesn’t quite have the pathos of Bub – it would be difficult, since at the start of The Bone Temple we see Samson doing business as usual, i.e., ripping off someone’s head and dragging their spine out of their neck-stump. Kelson, though, is a far more endearing character than the obsessed and unbalanced Logan. The scenes with him and an ever-more docile Samson are both amusing and touching and you feel increasingly worried about them both as the Jimmies close in.

If I have a criticism of The Bone Temple, it’s about how it depicts the other infected, the ones who aren’t Samson. They feel like a device that gets turned on and off according to the needs of the plot. Uninfected humans out in the open who need to be threatened? The infected are ubiquitous. Uninfected humans out in the open who need to have a chat by the campfire? The infected are nowhere to be seen. Also, near the end, I can’t understand why the infected don’t immediately swarm the bone temple when it’s lit up like a chandelier and blasting out Iron Maiden.

Otherwise, 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple is a hugely impressive achievement by Nia DaCosta, Alex Garland and their cast and crew. And while Ralph Fiennes won’t win an Oscar for his performance, much as he deserves to – zombie movies don’t win Oscars – Iron Maiden should at least get him onstage during the rest of their world tour.

© Columbia Pictures