From pixabay.com / © socialneuron

It’s Halloween today. In keeping with tradition on this blog, I’ll celebrate the occasion by displaying ten pieces of macabre, spooky or unsettling artwork that I’ve come across and liked during the past year.

To start on a musical note… Here’s a flutist painted by the late Polish artist Zdzislaw Beksinski, whose work suggested Hieronymus Bosch combined with H.R. Giger and frequently depicted apocalyptic hellscapes populated by wraith-like figures. By Beksinski’s standards, this is a fairly sedate and playful piece. Its ochre-bathed figure is characteristically skeletal, but what impresses is how its multiple fingers, knuckles, joints, bones and tendons fuse chaotically to the flute and become a grotesque mechanism that’s an extension of it.

Beksinski met a tragic end in 2005 – after a traumatic few years during which he’d seen the death of his wife and the suicide of his son, he was murdered in a dispute over a small sum of money. Still, interest in his art has burgeoned since his death and there’s now a host of stuff about him on YouTube.

Moving eastwards from Poland to Ukraine – yes, a place that’s suffered plenty of real-life horror in the past two years. Yuri Hill is a Kiev-based artist who specialises in digital painting and whose work often depicts things worryingly pagan and primordial lurking in the forest. This piece is particularly good. As you study its crepuscular grey-blue murk, more and more details filter into view – not just the drooping, feathery branches of towering conifers, but the strange, bestial furriness of the figures and the Herne-the-Hunter-like antlers sprouting from their heads. The fact that they’re moving about on stilts just adds to the strangeness. For those of you wanting to see more of his work, Hill’s Instagram account is accessible here and his page on artstation.com here.

© Yuri Hill

From folk-horror to J-horror, i.e., Japanese horror, whose psychological, supernatural and urban-myth-derived traditions clearly inform this painting. Entitled Red Laugh, it’s the work of Yuko Tatsushima, who’s been described as both a ‘rockstar’ and an ‘outsider’ in Japanese painting. Even before we get to the grotesque subject matter, with the face missing an eyeball and some prominent, autopsy-like stitches running up its throat, the scratchy paint-strokes almost make you wonder if the artist did it with broken, bloody fingernails.

Indeed, the composition has a howl of rage about it that’s common in Tatsushima’s work. It frequently addresses sexual oppression, harassment and assault, things Japanese society – all societies, for that matter – often tries to look away from and things the artist has been a victim of herself. Such is the Francis Bacon-style intensity of Tatsushima’s creations that this YouTube film about her comes with a warning that its images might be ‘too disturbing for more sensitive viewers’.

© Yuko Tatsushima / From sugoii-Japan.com

That seems far, far removed from my next picture, which celebrates the cosy tradition of classical British horror fiction, set in wooden-panelled Victorian and Edwardian drawing rooms and populated by crusty, tweedy gentlemen. It’s by Charles W. Stewart, one of the few people who can claim to have been born in the Philippines but brought up in Galloway in Scotland, and whose enthusiasm for illustrating was apparently matched for his enthusiasm for ballet and costume design. Stewart, clearly a man of many interests, selected the stories and did the illustrations for a 1997 collection entitled Ghost Stories, and Other Horrid Tales, which was published four years before his death. The volume includes fiction by Sheridan Le Fanu, Robert Louis Stevenson, Lafcadio Hearn, Vernon Lee, M.R. James and Walter de la Mare.

Stewart’s illustration here, which shows an antiquarian discovering he has unexpected company whilst engaged in some nocturnal research, is presumably for M.R. James’s Canon Alberic’s Scrap-Book. The story ends with the fictional equivalent of a cinematic jump-scare: “…his attention was caught by an object lying on the red cloth just by his left elbow… Pale, dusky skin, covering nothing but bones and tendons of appalling strength; coarse black hairs, longer than ever grew on a human hand; nails rising from the ends of the fingers and curving sharply down, grey, horny and wrinkled…”

One of the greatest early scares in film history occurred in the 1925 silent version of Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera, which starred the remarkable Lon Chaney Sr in the title role. The mysterious masked phantom gets unmasked whilst playing at his beloved organ. Unable to stop herself, the singer Christine (Mary Philbin) whips the mask off from behind. The audience is confronted by the phantom’s horribly gaunt, stretched and skull-like face in the screen’s foreground – at this point, supposedly, some 1925 audience-members fainted. Then he turns around and the audience is traumatised a second time as they see Christine reacting in horror to his deformed visage too. Anyway, here’s a regal portrait of Chaney Sr’s Phantom of the Opera, sans mask, courtesy of Pittsburgh artist Daniel R. Horne, who’s painted a number of classic movie monsters.

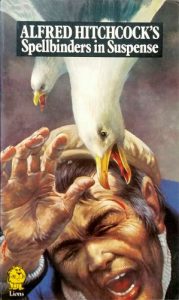

There were scares a-plenty in the films of director Alfred Hitchcock. Indeed, he was perhaps cinema’s greatest practitioner in the genres of suspense and horror. So popular was Hitchcock among the public in his heyday that he licensed his name to dozens of collections of crime, mystery, thriller, espionage and horror short stories, whose titles ranged from Alfred Hitchcock’s Coffin Break (1974) to Alfred Hitchcock’s Hard Day at the Scaffold (1967), from Alfred Hitchcock’s Monster Museum (1965) to Alfred Hitchcock’s Sinister Spies (1966). These had introductions purporting to be written by the great man himself, but they were actually penned by publishing-house editors.

I’m partial to this cover illustration from the collection Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbinders in Suspense (1967), which includes Daphne du Maurier’s short story The Birds (alongside the likes of Richard Connell’s The Most Dangerous Game, Roald Dahl’s Man from the South and Robert Bloch’s Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper). Hitchcock, of course, filmed The Birds in 1963. The cover’s artist isn’t identified, but with those brutally-pecky gulls, and the victim’s screaming face, he or she does a good job of capturing the directness of du Maurier’s grim, claustrophobic original. Hitchcock’s treatment of it is more mannered and expansive, though still brilliant.

© Lions, London

While many modern artists have taken their inspiration from the cinema, the American painter and illustrator Burt Shonberg could boast that his work turned up in movies. Most notably, Shonberg provided the disturbingly dark-eyed and corpse-faced portraits of former members of the Usher family, which Roderick Usher (Vincent Price) shows to Philip Winthrop (Mark Damon) in Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptation House of Usher (1960).

Acclaimed as ‘the premier psychedelic artist of Los Angeles’ from the 1950s until his death in 1977, Shonberg’s work extended beyond hippy-era psychedelia and he flirted with cubism and did some fine pen-and-ink drawings. Here, however, I’m showing a languid, sultry composition entitled Magical Landscape or Lucifer in the Garden, which depicts an unsettlingly youthful version of Auld Nick. Obviously, representations of the Devil abound throughout the history of art, but what makes this one memorable are those particularly long pasterns and the strange little sphinx resting on his lap.

From cvltnation.com

In these art-themed Halloween posts, I also like to honour the festival that comes straight after Halloween – Mexico’s Dia de Muertos, the Day of the Dead, at the start of November, which features skulls and skeletons as a major theme. This next picture gets straight to the point. It’s by David Lozeau, a San Diego artist who’s dedicated much of his career to creating Day of the Dead-inspired artwork, and it shows two skeletons raucously celebrating… Day of the Dead. I assume that yellow stuff in the señorita skeleton’s bottle is reposado tequila, which acquires its colour from the oak barrels it matures in.

There’s also an admirable directness about this picture, of a vampire lady, by Argentinian artist Hector Garrido, who passed away in 2020 when he was in his nineties. Put Garrido’s name into Google Images and you’ll be assailed by countless pictures of G.I. Joe toy-packaging, which he designed back in the 1980s. However, his main work was creating book covers, most popularly for gothic and romantic novels and for the series about the wholesome juvenile sleuths Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys. But Garrido’s CV includes covers for the likes of John Brunner, Ramsey Campbell, Agatha Christie, John Christopher, Robert A. Heinlein, Richard Matheson and Robert Silverberg too.

This one comes from a book called A Walk with the Beast, actually a collection of ‘vintage tales of human monsters and were-beasts’ edited by Charles M. Walker. The stories include one by Vernon Lee, who also appeared in Charles W. Stewart’s Ghost Stories, and Other Horrid Tales. ‘All fun’ says the book’s single reviewer on amazon.com, so evidently it ‘does what it says on the tin’.

© Avon Books

And finally, for my final picture, it’s back to Japan for something similarly fun and schlocky – not the cover of a book but one of a Japanese comic-book. This effort by the late manga-artist Marina Shirakawa is wonderfully sinewy and eye-catching. It’s full of typical manga-style details – see those simultaneously hideous and gleeful ghouls in the background – and peculiarly Japanese ones, such as the heroine’s sailor-suit school uniform. Its colour scheme of dark, blue-grey hues, with smudges of blood-red at the back, is memorable too.

© From monsterbrains.blogspot.com

And that’s it for another year. Happy Halloween…