© Pan Books

One more horror-themed reposting just before Halloween…

Michael Gove, well-known cokehead, Aberdonian nightclub boogie-king and England’s Education Minister from 2010 to 2014, would be disappointed in me. When I was a lad, my usual reading material was not the likes of George Eliot’s Middlemarch, which in 2013 Gove famously said he wanted to see the nation’s youth reading.

Rather, when I was 11, 12 or 13, I commonly had my nose stuck in works by such authors as Sven Hassel, James Herbert and Guy N. Smith, meaning that I didn’t become conversant in the effects of the Great Reform Act of 1832 or in the gradual diminution of the ideals of Dorothea Brooke, which Eliot wrote about in her 1871-1872 masterpiece. I did, however, end up learning a lot about German Panzer divisions wreaking bloody havoc on the Russian front during World War II, about chemical weapons leaking out of military laboratories in the form of thick swirling fogs and driving all who come in contact with them murderously insane, and about giant mutant crabs going on the rampage and eating people. Knowing such things prepared me a lot for adult life.

I also spent a lot of time reading, in the form of tatty paperbacks that in the school playground and on the school bus were constantly borrowed, read, returned, borrowed again and read again, a series called The Pan Book of Horror Stories. The first of this series had been published in 1959, under the editorship of the strikingly named Herbert Van Thal, a literary agent, publisher and author whom the critic John Agate had once likened to ‘a sleek, well-groomed dormouse’. The first few volumes of horror stories that Van Thal edited for Pan Books consisted largely of classical stories from well-known horror writers and more ‘mainstream’ (whatever that means) writers who’d dabbled in the genre; and their quality was generally held to be high.

By the late 1960s, however, Van Thal was filling each new compilation with more and more stories from new writers, many of whom were taking advantage of a more permissive era to see what they could get away with in terms of violence, gore and general unpleasantness. Serious horror writers and fans became quite sniffy about the books. Ramsey Campbell, Britain’s most acclaimed living horror writer, has said: “I did like the first one when I was 13 years old, but I thought the series became increasingly illiterate and disgusting and meritless.”

When my schoolmates and I started reading them in the 1970s, the latest editions of The Pan Book of Horror Stories were low in literary quality but high in disgusting-ness, which suited our jaded, beastly little minds fine. I’m still psychologically scarred by Colin Graham’s The Best Teacher in the ninth collection, which was about a psychopath who decides to write a manual for aspiring horror writers, instructing them in what dismemberment, disembowelment and various acts of torture really look and sound like. To this end, he kidnaps a horror writer and starts dismembering, disembowelling and torturing him whilst recording everything with a camera and tape recorder. Anyone who thinks that the horror sub-genre of ‘torture-porn’ began with Eli Roth’s movie Hostel in 2005 ought to check out Graham’s grubby epic from a few decades earlier.

© Pan Books

To be fair, the later Pan collections did feature then-up-and-coming, now-well-regarded writers like Tanith Lee, Christopher Fowler and, ahem, Ian McEwan. However, by the 1980s (and after Van Thal’s death), the series was clearly on its last legs. It resorted to ransacking Stephen King’s famous anthology Nightshift (1978) and reprinting stories like The Graveyard Shift, The Mangler and The Lawnmower Man. This was unwise, since anybody inclined to read the Pan horror series had probably read Nightshift already. The final volume, the thirtieth, had a very limited print run and if you ever lay your hands on a copy, it’s probably worth a lot as a collector’s item.

A while ago in a second-hand bookshop I discovered a copy of The First Pan Book of Horror Stories. This, alas, was unlikely to be sought by book collectors, since the copy looked like something had chewed, swallowed, partly-digested and regurgitated it. At least it was still readable, so I got a chance to sample the original instalment in this famous, or infamous, series. I was curious to know if it deserved the praise Ramsey Campbell had given it and also to see how different it was from the more disreputable stuff that came later.

My first impression was that the stories in this collection weren’t how I’d have organised them. I’ve heard writers whose works were printed in the later Pan books grumble about Van Thal’s abilities as an editor, and it’s hard to see why stories as similar as Hester Holland’s The Library and Flavia Richardson’s Behind the Yellow Door (both about hapless young women who are hired as private secretaries by older, plainly-batty women and who meet gruesome fates), or Oscar Cook’s His Beautiful Hands and George Fielding Eliot’s The Copper Bowl (both about exotic, grotesque revenges and tortures inflicted by East Asian people – at least one of them struck me as racist) should end up in the same book. In fact, Eliot’s story follows immediately after Cook’s, thanks to Van Thal’s strange policy of arranging the stories by the alphabetical order of their authors’ surnames.

I also noticed how stories I’d read elsewhere and greatly enjoyed in my youth now, sadly, seem a bit duff. I loved Hazel Heald’s The Horror in the Museum when I read it as a 13-year-old. Heald, incidentally, wrote it under the tutelage of H.P. Lovecraft, whose influence is obvious in the ornate prose-style. However, a modern rereading suggests that Heald (and Lovecraft) could’ve cut the story’s length by about 20 pages without losing any of its plot points.

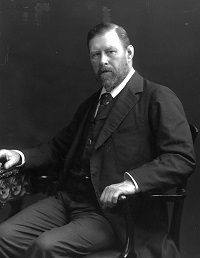

Meanwhile, Bram Stoker’s The Squaw, another tale I had fond memories of, seems much poorer now thanks to one of its characters being an American tourist called Elias P. Hutchinson. If Hutchinson was what Stoker believed all Americans sounded like, spewing toe-curling things like ‘I du declare’ and ‘I say, ma’am’ and ‘this ole galloot’ and ‘durned critter’, I can only say that Stoker needed to go out and do some research. Still, despite some glaringly obvious failings, both The Horror in the Museum and The Squaw benefit from having cracking denouements.

From wikipedia.org

The Horror in the Museum is one of the few stories in the collection that contains a monster. (And what a monster it is: “globular torso… bubble-like suggestion of a head… three fishy eyes… foot-long proboscis… bulging gills… monstrous capillation of asp-like suckers… six sinuous limbs with their black paws and crab-like claws…”). Apart from The Kill by Colonel Peter Fleming, a werewolf story penned by none other than Ian Fleming’s older brother, the rest of the stories are fairly monster-free, depending on psychological terrors for their impact. Indeed, C.S. Forester’s The Physiology of Fear is a horror story in an unusually literal sense. It deals with a particularly horrific episode in human history, the Nazi concentration camps. It also features a German scientist engaged in research, with the Third Reich’s support and with prisoners from the camps as his guinea pigs, into the emotion of horror as it arises in the human psyche. And the story’s ending isn’t conventionally horrific. Instead, the scientist is ensnared in an ironic and satisfying twist worthy of Roald Dahl.

Also not a horror story in any conventional sense is Muriel Spark’s The Portobello Road. It qualifies as a ghost story, but most of all it’s a mediation on the nature of friendship as it survives, or doesn’t survive, from childhood into adulthood. This being Spark – whose most famous creation, Miss Jean Brodie, was simultaneously a prim middle-class Edinburgh schoolmistress and a fascist – the story has a bitter, vinegary flavour. None of its characters are particularly pleasant and none seem to deserve long-term friendship. In fact, the one character who tries to keep those friendships alive is the one who, ultimately, commits the story’s single, shocking act of violence.

Meanwhile, I reacted to the sight of Jack Finney’s Contents of the Dead Man’s Pocket as if an old friend had suddenly hoven into view. Not that I’d encountered this particular story before, but it conjured up fond memories of American writers like Richard Matheson, Robert Bloch, Ray Russell and Charles Beaumont, who in the 1950s seemed to keep their rents paid by pumping out short stories for the likes of Playboy magazine and TV scripts for the likes of The Twilight Zone (1959-64) and Boris Karloff’s Thriller (1960-62). In admirably direct and diamond-hard prose, their tales would detail the world turning suddenly and inexplicably weird for citizens of conformist post-war America, for both dutiful suburban wives in nipped-in-at-the-waist housedresses and office-bound men in grey-flannel suits.

From fictionunbound.com

Finney, most famous as the author of the sci-fi horror novel The Body Snatchers (1955), which has been filmed four times and shows conformity taken to a nightmarish extreme, starts his story thus: “At the little living room table Tom Benecke rolled two sheets of flimsy and a heavier top sheet, carbon paper sandwiched between them, into his portable.” A half-dozen pages later, events have lured Benecke away from his portable typewriter and embroiled him in a vertiginous life-or-death struggle just outside his apartment window. It calls to mind the Stephen King short story The Ledge, another one that appeared in his collection Nightshift. I doubt if the similarity between the two stories is a coincidence, King being a big admirer of work from this era of American story-telling.

Also deserving mention are Oh Mirror, Mirror, a claustrophobic item penned by the great Nigel Kneale; Raspberry Jam, Angus Wilson’s poisonous take on the snobbery of old people who no longer have anything to be snobbish about; and Serenade for Baboons, a colonial horror by Noel Langley.

Inevitably, a couple of clunkers find their way into the book too. Anthony Vercoe’s Flies wouldn’t be such a bad story if the writer hadn’t swamped his prose with exclamation marks. I can’t remember encountering so many of the damned things in ten pages of prose before and the result is almost unreadable. Meanwhile, The House of Horror is one of a series of short stories that American pulp writer Seabury Quinn wrote about a psychic investigator called Jules de Grandin. De Grandin is French and seemingly meant to be a supernatural version of Hercule Poirot (who, I know, was actually Belgian). Unfortunately, Quinn gives him a patois that is as cringe-inducing as Elias P. Hutchinson’s Americanisms in The Squaw: “Sang du diable…! Behold what is there, my friend… Parbleu, he was caduo – mad as a hatter, this one, or I am much mistaken!”

On the whole, though, I found The First Pan Book of Horror Stories a rewarding read. I now look forward to tracking down the other, earlier instalments in the series – those ones that came out before Herbert Van Thal decided to crank up the levels of nasty, schlocky stuff, in order to satisfy the blood-crazed savages amongst his reading public.

Blood-crazed savages such as my twelve-year-old self…

© Pan Books