© BBC / Nine Network / Western-World Television Inc

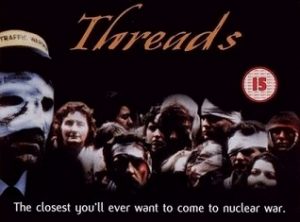

I can’t imagine what has prompted me to repost in April 2022 this entry about Threads, the BBC’s terrifying 1984 drama about a nuclear strike on Britain, which I’d originally put on this blog four years ago to coincide with a remastered version of it being released on Blu-ray. I mean, it’s not as if anything is happening in the world at the moment to kindle fears of a holocaustic nuclear war breaking out. Is there?

It’s said that everyone remembered where they were and what they were doing on November 22nd, 1963, when they heard that President John F. Kennedy had been shot. Likewise, I remember where I was and what I was doing on the evening of September 23rd, 1984, when BBC2 broadcast the apocalyptic drama Threads.

I was staying in the youth hostel in Aberdeen, with my second year as an undergraduate at Aberdeen University due to begin in a fortnight’s time. Having worked abroad for the summer, I was now back in the city trying desperately to arrange accommodation for myself for the year ahead. I’d spent the past few days trudging around flat-hunting without any luck and, to make matters worse, I’d just been informed that I wouldn’t be eligible for a student grant for the next year either. So I was feeling pretty low about my residential and financial situation that evening when I wandered into the youth hostel’s lounge and sat down among a crowd of hostellers who were about to watch something on television called Threads, a much-anticipated documentary-drama showing what would happen if a nuclear conflict broke out between America and the Soviet Union and the UK was struck by 210 megatons of nuclear weaponry.

It’s fair to say that by the time Threads ended 112 minutes later, my mood had not improved any. Mind you, nobody else in the lounge looked like they were bursting with joie de vivre. Bill Dick, the hostel’s usually easy-going and affable head-warden who’d been in the audience, couldn’t have looked more down in the dumps if he’d been buried to his neck in garbage. (I got to know Bill four years later when I spent a summer working at the hostel as a warden and had him as my boss.)

A while ago, something compelled me to view Threads again. Here are my thoughts on it from a 21st century perspective. I should warn you that the remainder of this blog-entry will contain spoilers, though you’ve probably gathered already that in Threads absolutely nothing good happens.

Directed by Mick Jackson and written by the late Barry Hines, author of the 1968 novel A Kestrel for a Knave that a year later established Ken Loach as a cinematic force when he filmed it as Kes, Threads consists of three sections. There’s an initial 45 minutes showing life during the build-up to the cataclysmic nuclear strike. Then there’s another 45 minutes showing the strike and its immediate aftermath. And lastly there’s a 25-minute epilogue chronicling Britain a year, a decade, ultimately 13 years into the future when, with its natural environment, economy and social infrastructure pulverised, the country reverts to the Middle Ages. That’s the Middle Ages minus the chivalry, balladry and pageantry, but with plenty of fallout, nuclear winters, depleted ozone, ultraviolent radiation, cataracts, skin cancer and genetic damage.

The gruelling central section imprinted itself on my 19-year-old memory. I’ve carried its images around in my head ever since: milk bottles melting on doorsteps in the heat of a nuclear detonation, a charred cyclist (still on his bike) lodged amid the branches of a burning tree, cats igniting, dolls melting, a crazed woman squatting amid the rubble cradling her baby’s burnt corpse, a traffic warden with a bandage-swathed face holding off a starving mob with a rifle, doctors in an overrun hospital sawing away a leg while the un-anaesthetised patient screams through a gag, and several dozen other things involving flames, rubble, cadavers, rats, blood, wounds, excrement, vomit and general mayhem and horror. In particular, I’ve never forgotten the moment when a mushroom cloud rises terrifyingly above the skyline, causing one poor woman to wet herself in the middle of a street – something that led to the actress Anne Sellors having the briefest and most poignant entry ever on IMDb.

© BBC / Nine Network / Western-World Television Inc

But having seen Threads again, I now appreciate the queasy effectiveness of the opening section too. Here, Hines and Jackson establish the focus of their story, two families in the Yorkshire city of Sheffield. These are the working-class Kemps and the middle-class Becketts. The Kemps’ eldest boy Jimmy (Reece Dinsdale) has been courting the Becketts’ daughter Ruth (Karen Meagher) and Ruth has just realised she’s pregnant. Jimmy and Ruth resolve to get married and start renovating a flat to live in while their families uneasily make each other’s acquaintance. Interestingly, this reflects the uneasy working relationship between Hines and Jackson themselves. According to Threads’ Wikipedia entry, the working-class Hines saw Jackson as something of a middle-class prat.

Meanwhile, ominously, news reports chatter in the background about escalating superpower tensions in the Middle East. The characters are initially oblivious to what’s brewing. Early on, we see Jimmy fiddling with his radio, wanting to get away from some boring news bulletin about the crisis and find the latest football results. Apathy gradually changes to shoulder-shrugging helplessness, something summed up by Jimmy’s workmate Bob (Ashley Barker). In the pub, he declares that they might as well enjoy themselves now because there’s bugger-all else they can do. Plus, if things do kick off, he hopes he’ll be ‘pissed out of his mind and straight underneath it.’ Ironically, Bob survives after nearly everyone else has perished and we last see him tucking into the raw and probably irradiated flesh of a dead sheep.

By the time the characters try to respond to what’s coming, it’s too late. The bomb goes off while the hapless Kemps are still assembling a fallout shelter comprised of a couple of doors propped against a living-room wall. The Becketts, being posher, have a cellar to retreat into. Not that they fare any better in the long run.

For me, it’s this opening section that brings home what Threads is about. A preliminary narration talks about the economic threads necessary for a society to function: “…everything connects. Each person’s needs are fed by the skills of many others. Our lives are woven together in a fabric. But the connections that make society strong also make it vulnerable.” However, my impression is that the truly important threads – which are obliterated once the missiles hit their targets – are the ones between people, of feeling and compassion, which have been refined by centuries of civilisation and, today, are the essence of what it means to be human.

Thus, we see Jimmy (whom we know has been cheating on Ruth and is a bit of a tosser) standing in the aviary in his family’s back garden, doting over the birds kept there. We see Mr and Mrs Beckett (Henry Moxon and June Broughton) trying to look after an ailing relative discharged from hospital after the NHS is ordered to clear its wards in anticipation of a flood of war casualties. We see Clive Sutton (Harry Beety), the local government official put in charge of an emergency team that will run things from a bunker underneath Sheffield City Council, attempting to reassure his nervous wife. But empathy for our fellow creatures rapidly disappears as, in the war’s aftermath, humanity degenerates into a shell-shocked, zombie-like rabble fixated only on its own, scrabbling-in-the-dirt survival.

This is made explicit in Threads’ final stages when, years later, we’re introduced to Jane (Victoria O’Keefe), the daughter of Ruth and Jimmy. When Ruth dies, sick, exhausted, blinded by cataracts and looking decades older than her true age, an impassive Jane reacts by stealing a few items from her mother’s corpse and then clearing off. The few kids born post-holocaust are a scary bunch, by the way. Their language is limited to phrases like “Gizzit!” and “C’mon!” and they generally act like feral mini-Neanderthals.

Threads came in the wake of the bleak 1983 American TV movie The Day After, directed by Nicholas Meyer, which depicted the effects of a nuclear strike on Kansas City and caused a considerable stir on both sides of the Atlantic. But while I like The Day After, I think the altogether more graphic and relentless Threads beats it to a bloody pulp. For one thing, Meyer’s film is disadvantaged by its cast of familiar actors like Jason Robards and John Lithgow, which means you can’t ever forget you’re watching a dramatic fabrication. In Threads, the cast is comprised of unknown performers, which adds to its harrowing sense of authenticity.

That said, saddoes like myself might recognise David Brierley, who plays Ruth’s father, as the voice of K9 in the 1979-80 series of Doctor Who; and a couple of voices heard from the early blizzard of news reports are familiar, like Lesley Judd from the BBC’s famous kids’ magazine programme Blue Peter, and Ed Bishop, star of the Gerry Anderson sci-fi show UFO (1970). I’m glad Jackson decided not to go with his original casting idea, which was to use actors from the venerable north-of-England TV soap opera Coronation Street – disturbing though the sight of Jack and Vera Duckworth puking their guts up in a makeshift fallout shelter would have been.

Threads also contains the sonorous tones of the great voiceover actor Patrick Allen, whom the UK government had hired to narrate its Protect and Survive public information films that would be broadcast if nuclear war looked imminent. By 1984, the media had got hold of these films and discussed them at length and they’d been derided for their epic uselessness if Armageddon really happened. (At one point in Threads we hear Allen crisply and matter-of-factly advising the public on how to deal with corpses: “…move the body to another room in the house. Label the body with name and address and cover it as tightly as possible in polythene, paper, sheets or blankets.”) Earlier in 1984, Allen’s Protect and Survive voice-work had been sampled in Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s hit single Two Tribes – for which he sportingly added the lines: “Mine is the last voice you will ever hear. Do not be alarmed.”

The futility of Protect and Survive and officialdom’s attempts to deal with the holocaust generally are embodied in Threads by Sutton and his team, who utterly fail to provide leadership and control once the bombs have gone off. Trapped in their bunker under the rubble of the flattened council building, with insufficient training, malfunctioning equipment and limited supplies of food, water and air, they succumb to bickering, despondency, hysteria and – finally – asphyxiation. Predictably, when order is re-established in Sheffield, it’s pretty brutal in nature.

© BBC / Nine Network / Western-World Television Inc

Brutal too is the narrative as it moves forward in time, with Telex-type captions flashing up on the screen giving statistics about fallout levels, the nuclear winter, the ozone layer, epidemics and an ever-rising death-toll. Things climax with the now-teenaged Jane giving birth after she’s been raped by another of the feral kids. The baby is stillborn and deformed, and Threads’ last image is a freeze-frame of Jane’s face as she recoils in horror from it. Early on, Jimmy’s kid brother Michael (Nicholas Lane) had embarrassed his parents by asking, “What’s an abortion?” Threads ends with the implication that humanity has unwittingly aborted itself.

It isn’t perfect. Thanks to budgetary restrictions, there’s a reliance on stock footage and stills from previous wars and conflicts, which don’t necessarily look like they’re occurring in Sheffield in 1984. And despite valiant efforts by the make-up department, the actors playing the long-term survivors are a bit too plump and healthy-looking – by then they should have resembled death-camp inmates. Additionally, the fact that Threads takes place in a pre-Internet, pre-social media world gives it a quaint distance now. Imagine the reaction if the equivalent events happened today. While the first warheads exploded over Britain, Twitter would be babbling with idiots blaming everything on immigrants or Muslims or woke-ism or the Covid-19 vaccine. But, as a traumatic account of what might engulf us if our political leaders are possessed by a moment of trigger-happy madness, it’s still unbeatable.

And, in April 2022, with Vladimir Putin making threatening noises about nuclear retaliation against NATO for helping to thwart his military campaign in Ukraine, Threads seems no less relevant than it did 38 years ago. That’s a sentence I take no pleasure in writing.

© BBC / Nine Network / Western-World Television Inc