© Jim Barton / From wikipedia.org

Today, September 18th, is the tenth anniversary of 2014’s referendum on Scottish independence. Yes, a decade has now passed since the Scottish electorate voted, by a majority of 55% to 45%, in favour of remaining part of the United Kingdom.

In the referendum’s aftermath, I was inspired to write a short story entitled Mither. This poked fun at a narrative peddled by the mainstream media that the referendum had turned Scotland into a bitterly divided country – parents, children, siblings who’d previously lived together in harmony suddenly transformed into rabid yes-sers and no-ers who were at each other’s throats, families in turmoil, that sort of thing. It also paid homage to a classic and highly influential movie. Needless to say, the story was too weird and too daft to ever get published.

However, ten years on, I thought I would take advantage of the occasion and post it here. I now give you… Mither.

© Labour for Independence / From wikipedia.org

I must have dozed while I sat in the office and read the literature that’d landed on our porch floor that morning. I hadn’t heard her go out. I only heard the porch door scrape open and shut as she came back.

‘Mither,’ I said when she entered the office. ‘You were outside.’

She settled into the armchair with the tartan-patterned cushions that’d been her seat – her throne, we called it – when she ran the business by herself. Now that I was mostly in charge, I had my own seat in the office but I kept the throne there should she want to use it. She smoothed her skirt across her knees. She was a modern-minded woman – at times too modern-minded because she had some ideas you’d expect more in a giddy teenager – but she avoided trousers and stuck to old-fashioned long skirts. ‘Aye, Norrie. I’ve been out and about.’

I didn’t like the sound of that but before I could quiz her she leaned forward from the throne and took the leaflet out of my hand. ‘What’s this you’re reading? Don’t say they’ve shovelled more shite through our door.’

It pained me to hear her genteel voice soiled by coarse language. But I stayed patient. ‘It’s actually interesting, Mither. It’s an interview with a normal young couple, a professional young couple, about what might happen if the referendum result is…’ I searched for a word that’d cause minimum offence. ‘Unexpected.’

Mither sighed and her eyes swivelled up in their sockets.

‘Now I ken you’re sceptical, Mither. But they seem decent. He’s called Kenneth and she’s called Gina. And they’re worried about the effect independence would have on them.’

Mither’s eyes swivelled down again. Then I saw them twitch from side to side while they scanned the text on the leaflet.

I pressed on. ‘It wouldn’t have a good effect, Mither. It’d be bad for them.’ Why did my voice tremble? Why was I afraid? ‘The financial uncertainty. How would decent hardworking people like them – like me – cope if all the business fled south and the prices shot up? And the banks… Why, I read in the paper the other day about an expert who said the bank machines would stop dispensing cash if the vote was yes.’

‘Does,’ asked Mither, ‘this say what Kenneth does for a living?’

‘And even if we still have cash, Mither, what would our currency be? We won’t have the pound – George Osborne and Ed Balls down in Westminster won’t allow it. We’ll have to make do with some banana-republic-type currency. Or worse, the euro!’

‘Norrie,’ said Mither, ‘calm down. Does this leaflet actually say what Kenneth’s job is?’

‘Aye, of course it does.’ I faltered. ‘Well, no. Maybe it doesn’t.’

She sighed. ‘It certainly doesn’t, Norrie. And I’ll tell you why.’ She raised the leaflet so that I could see a picture of Kenneth, Gina and their children on it. She placed a fingertip against Kenneth. ‘It’s because he’s Kenneth Braithwaite, who’s one of our local councillors. One of our Conservative Party councillors. But that fact isn’t mentioned here. It pretends that he’s an ordinary unbiased person like you or me.’

I chuckled nervously. ‘Now Mither. I wouldn’t say you were unbiased.’

Mither rose from her throne. ‘I am unbiased. My mind’s open to facts and I form opinions and make decisions based on those facts. Facts, mind you. Not the propaganda, smears and scaremongering that’s poured out of the political, business and media establishments during the last year. Not the drivel that’s clogged and befuddled your impressionable young mind.’

Before I could reply, she tore the leaflet down the middle and returned it to my hands in two pieces. Then she hustled out of the office and shut the door behind her with enough force to make a stuffed owl wobble and almost fall off a nearby shelf. I heard her shoes go clacking up the stairs and then another door slam, presumably the one leading into her room.

I seethed. How I hated, how I loathed this referendum! Setting family members against one another day after day! I looked at the leaflet again and realised that by a creepy coincidence Mither had ripped it down the middle of the family-picture. Now Kenneth and a little boy occupied one half of it while Gina and a little girl were sundered and separate in the other half.

A family literally torn apart.

***

I hated the referendum but I couldn’t wait for the day of it, September 18th, to come – and take place and be over with. The problem was that the time until then seemed to pass very slowly. And during this time it felt like a war of attrition was being waged against me. I grew more tired and depressed the longer those separatists raved in the media and on the streets and from the literature they popped through the slot in our porch door. A rash of yes stickers and posters spread along the windows in the street-fronts of our neighbourhood. Some of them even appeared on the houses of people I’d thought were decent and sensible.

I began to panic. God, could it happen? I had visions of the doors padlocked and the windows boarded up on the old family business and Mither and I living in poverty alongside hundreds of thousands of other suddenly-penniless Scots. While around us, food prices and fuel prices skyrocketed, the banks and financial companies whisked all their offices away to London, the housing market disappeared into a giant hole, the hospitals became like those in the developing world, and terrorist cells congregated in Glasgow and Edinburgh and prepared to attack England across the new border.

But worst of all was the madness this referendum campaign inspired in Mither.

She sensed when I was worn out. While I was napping, or nodding off behind the desk in the office, or slumped in a stupor in front of the TV, she’d leave her room and creep down the stairs and do things.

These might be wee things. If I wasn’t in the office, she might use the computer and I’d discover hours later that it was open at frightful separatist websites like Bella Caledonia or National Collective or Wings over Scotland. The day’s Scottish Daily Express might disappear from the kitchen table and turn up, scrunched into a ball, in the recycling bin in the corner. Or if the Express was left on the table, any photographs in it of Alistair Darling or George Osborne might have shocking words like tosser or bampot graffiti-ed across them in Mither’s curly handwriting.

More worrying was her tendency sometimes to sneak outdoors. It would’ve been bad enough in normal times because she was too old and frail to be wandering the streets alone. But in these dangerous times, who knew what she was up to and who she was associating with?

© National Collective / From Stirling Centre of Scottish Studies

The evidence disturbed me. When I visited her room I found a growing collection of things that she could only have acquired during trips outside – little Scottish saltire and lion-rampant flags, booklets of essays and poems written in support of independence, brochures for events with sinister titles like Imagi-Nation and Yestival, posters where the word can’t had the t scrawled out so that they read can instead. She’d amassed badges, stickers and flyers with the word yes emblazoned on them. What a disgusting-sounding word yes had become to me. I’d contemplate Mither and imagine that horrible word spurting from her lips –

‘Yes! Yes! Yes – !’

And she’d argue. Goodness me, what had got into the woman to make her so bloody-minded? In between quoting names of people I’d never heard of, but who were undoubtedly up to no good, like Gerry Hassan, David Greig and Lesley Riddoch, she’d taunt me mercilessly.

‘So go on. Tell me. Explain. Why can we not be independent?’

‘Because… We can’t! We just can’t! We’re too… too…’

‘Too wee?’

‘Aye! Well, no. Not that, not only that. We’re also…’

‘Too poor?’

‘Aye, that’s true, Scotland’s too poor to be independent. But the main reason is that we’re…’

‘Too stupid?’

‘Och stop it, Mither! Stop! You’re putting words in my mouth!’

‘But you agree with that basic proposition? Scotland can’t be independent because it’s too small, its economy’s too weak and its people aren’t educated enough?’ She sighed. ‘That’s what we’re up against. A mass of our fellow Scots, yourself included, brainwashed by the establishment into believing their own inferiority!’

I stormed out of the room at that point. What horrible people had she been talking to?

A few weeks before the referendum-day, her madness reached what I assumed was its peak. After the last guests had left the premises and after I’d washed and put away the breakfast things, I took the vacuum cleaner into the porch and started on the carpet there. It took me a minute to notice something odd about the rack on the porch wall where I stored leaflets about local attractions that our guests might be interested in: Rosslyn Chapel, Abbotsford, Traquair House, Melrose Abbey and so on. The leaflets in the rack had changed. The tourist ones had disappeared. In their place were different ones. Political ones.

© Women for Independence / From wikipedia.org

I put down the vacuum-hose and approached the rack. Crammed into it now were leaflets I’d seen in her room advertising those sinister-sounding events like Imagi-Nation and Yestival and other ones promoting the unsavoury websites she’d consulted on the computer like National Collective, Bella Caledonia and Wings over Scotland. Also there were leaflets for organisations with different but strangely-repetitive names: Women for Independence, Liberals for Independence, Polish for Independence, Asians for Independence, English for Independence, Farmers for Independence… One organisation, whose leaflets were merely sheets of photocopied and folded-up A4 paper, was even called Hoteliers for Independence.

I couldn’t help reading that Hoteliers for Independence leaflet. It ended with the exhortation, ‘Please contact Hoteliers for Independence for more information at…’ and gave an address. My insides turned cold as I read the address. I found myself pivoting around inside the porch and facing different internal doors that led to different parts of the guesthouse. I half-expected one door to have hanging on it a sign that said HOTELIERS FOR INDEPENDENCE – THIS WAY.

Then I peered up towards the first floor, where a certain bedroom was located, and lamented, ‘Oh, Mither.’

***

One afternoon, close to September 18th, I woke from an unplanned doze at the desk in the office. I’d been dreaming. A voice in the dream had droned about – what else? – that ghastly referendum. Disconcertingly, back in the conscious world, the voice continued to talk to me. I realised it came from a shelf above me, where the radio was positioned between a stuffed gull and a stuffed pheasant. The radio was tuned in to a local station and the voice belonged to a newsreader. He was explaining that a politician, a Labour Party MP, was visiting our region today.

This MP had toured the high streets and town centres of Scotland lately. To get people’s attention he’d place a crate on the pavement, stand on top of the crate and deliver a speech from it. He’d speak bravely in favour of Great Britain and the Union of Parliaments and denounce the separatists and their vile foolish notions of independence. And I’d heard from recent news reports that the separatists hadn’t taken kindly to his tour. Well, as bullies, they wouldn’t. They’d gone to his speaking appearances with the purpose of heckling him and shouting him down.

Then the newsreader named the town the MP was due to speak in this afternoon. It was our town.

And immediately I felt uneasy because I realised I hadn’t seen or heard anything of Mither for the past while. I went upstairs and knocked on her door. There was no reply. The guesthouse was empty that afternoon and so I hung the BACK SOON sign in the porch-window, went out and locked the door after me. Then I headed for the middle of town.

It wasn’t hard to find where the Labour MP was speaking because of the hubbub. The MP seemed to have turned his microphone’s volume to maximum so that he could drown out the heckling and shouting from the separatists in his audience. I emerged from a vennel, onto the high street, and saw the crowd ahead of me. It contained fewer people than I’d expected. Some of them wore no badges and carried no placards – among them, I thought I glimpsed Kenneth and Gina from the brochure that Mither had ripped up – and some had badges and placards saying yes. Looming above everyone was the MP on his crate.

© Thomas Nugent / From wikipedia.org

The separatists present were trying to make themselves heard – without success, thanks to the MP’s bellowing voice and the amplification provided by the microphone. It wasn’t until I reached the edge of the small crowd that I could understand what they were saying.

‘Answer the question, Murphy!’

‘He won’t answer the question!’

‘Quit shouting, man, and answer the question for God’s sake!’

Then I saw a figure standing at the back of the crowd a few yards along from me. The figure wore a long flowing skirt, a woollen cardigan and a lacy Sunday bonnet that obscured its face. A handbag dangled from one of its elbows and a small egg carton was clasped in its hands. As I watched, the figure prised the lid off the carton, lifted one of the six eggs inside and stretched back an arm in readiness to throw it –

I rushed at her and shouted, ‘Mither! Oh my God!’

What happened next is confusing. I remember reaching her and knocking the carton from her hands so that eggs flew in all directions. I remember not being able to halt myself in time and crashing into her so that she fell and I fell too, on top of her. But then, somehow, I found myself lying alone on the ground. Mither had disappeared. She must’ve been sprightlier than I’d thought. She’d gathered herself up and hurried away and left me there.

One of the eggs had made its way into my right hand. Now it was a ruin of broken shell. Meanwhile, the yolks, whites and shell-pieces of other eggs formed a gelatinous mess on the front of my woollen cardigan.

Then I was being helped to my feet. Around me, I heard voices:

‘Who is it?’

‘Some auld lady.’

‘No, wait… Christ! It’s a man!’

‘It’s young Bates. You ken, Norrie Bates? Him that runs the Bates Bed and Breakfast?’

‘Why’s he togged out like that?’

Someone took my arm and led me away. Behind us, the MP, who seemed not to have noticed the commotion with Mither and me, kept roaring into his microphone. We turned a corner into a side-street and paused there. I identified the man steering me as Dougie Bremner, who was the proprietor of another B and B in the town, a few streets away from ours. He’d always seemed a gentle friendly type and it surprised me to see a yes badge stuck to his jacket lapel.

![]()

© Yes Scotland / From wikipedia.org

Dougie looked perplexed. He scanned me up and down as if my appearance was a puzzle he wanted to solve. ‘Norrie,’ he said at last. ‘I think you need to go home. As fast as you can manage.’

My head ached. Something was squeezing my skull, which in turn was squeezing my brain. I raised a hand and found my head enclosed in a lady’s bonnet. It exuded two ribbons that were knotted under my chin. In a final gesture of spite Mither must’ve fastened it on my head before she’d escaped. ‘Aye,’ I whispered. ‘I’ll go home.’

‘By the way,’ added Dougie, who seemed greatly troubled now. ‘How’s your mither? I haven’t seen her for a while.’

***

It was the morning of September 19th. The radio had disappeared from the office and I guessed it’d travelled upstairs to Mither’s room and informed her of the result. Still, in case she hadn’t heard, I felt obliged to go to her room and let her know.

She looked very small, thin and frail as she huddled there amid the paraphernalia she’d acquired, the flags, placards, badges, posters, leaflets and booklets. On the floor around her, in a serpentine coil, there even lay a blue-and-white woollen scarf with a pair of knitting needles embedded in one unfinished end of it. That was another lark she’d been up to. Knitting for independence.

Because she looked so weak and unwell now, I understood that she knew. The result seemed to have drained the life from her, leaving her a husk.

But I repeated the news. ‘Mither. It’s a no.’

She didn’t answer. No sound came from her mouth, which was stretched back in a rictus – if I hadn’t known she was grimacing in pain and dismay, I’d have thought she was grinning. I looked into her eyes, trying to find a glimmer of acknowledgement for me, a spark of recognition that I was standing before her. But the eyes were blank and gaping, almost like they weren’t eyes at all but two dark holes.

And although I was relieved and delighted about the result, I suddenly and inexplicably felt as though a part of me was dead.

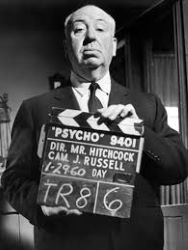

© Paramount Pictures / From tvtropes.org

With apologies to Robert Bloch, Alfred Hitchcock and Anthony Perkins. No apologies to Jim Murphy.

And tomorrow, on September 19th, I’ll raise a glass to the memory of the late Charlie Massie, who cheered me up after the result ten years ago by taking me on a pub crawl in Delhi. Though it probably wasn’t wise to go into the bar in the British High Commission, where we ended up stuck at a table in front of a giant TV screen, showing the news, with a lengthy interview in progress with Boris Johnson. Bojo was spewing shite about how great it was that the Jocks had embraced the Union and all the benefits that went with it. Those future Union benefits would include Brexit and having him as Prime Minister.