© Avala Film / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

It’s often said you don’t appreciate the value of something until after it’s gone. I felt like that last week on hearing of the death of the great Canadian actor Donald Sutherland. If someone had asked me to list my all-time favourite actors, I wouldn’t have thought of including Sutherland. Yet when he passed away at the age of 88 – having kept working in film and TV until last year – it suddenly struck me how much I was going to miss him.

Sutherland was an actor who could inhabit a range of personalities and project many different moods and emotions, yet whom you always recognised as, basically, himself. His characters might be heroic, dignified, fatherly, tragic, eccentric, sinister, venal, slow-witted, juvenile, gormless or demented – yet you always knew you were watching Donald Sutherland. Whoever he played, he retained that unique quality of Donald Sutherland-ness.

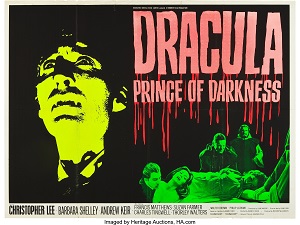

Born in St John, New Brunswick, Sutherland graduated from Victoria University with an interesting-sounding degree in Engineering and Drama, then relocated to Britain in 1957 and studied at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. A few years later, he found his way into Europe’s then-flourishing horror-movie industry. He appeared in the monochrome Italian-French chiller Castle of the Living Dead (1964), starring Christopher Lee, directed by Warren Kiefer, and with a 20-year-old Michael Reeves, who four years later would make 1968’s masterly Witchfinder General, working as assistant director. No doubt for budgetary reasons, Sutherland was cast in three roles, most amusingly in drag, as a witch. He played a good-natured simpleton in Hammer Films’ Fanatic (1965), a blend of the low-key psychological thrillers the studio made when it wasn’t cranking out full-blooded gothic-horror melodramas and the fashionable 1960s sub-genre of ‘hagsploitation’ – the hag here being a dangerous religious nutcase played by Tallulah Bankhead. If the cast wasn’t interesting enough with Sutherland and Bankhead, it also included Stephanie Powers, Yootha Joyce and Peter Vaughan, future stars of TV shows Hart to Hart (1979-84), George and Mildred (1976-79) and Porridge (1974-77) respectively.

© Amicus Productions / Paramount Pictures

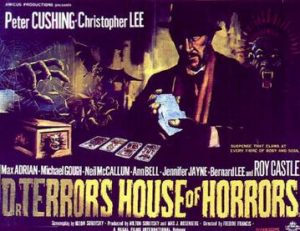

The best remembered of Sutherland’s early horror films is Dr Terror’s House of Horrors (1965), directed by Freddie Francis and produced by Milton Subotsky and Max J. Rosenberg – the first of seven anthology horror movies that Subotsky and Rosenberg’s British-based Amicus Productions would specialise in. To be honest, I don’t think the film’s five stories are up to much, but the framing device, wherein five night-time travellers find themselves sharing a train compartment with the mysterious Dr Shreck (Peter Cushing), who uses Tarot cards to foretell each man’s future, is wonderfully atmospheric. Dr Terror also has a fascinating cast. In addition to Sutherland and Cushing, there’s Christopher Lee (again) and another horror-movie veteran, Michael Gough; trumpeter, tap-dancer and TV presenter Roy Castle; disc jockey Alan ‘Fluff’ Freeman; and the original M from the James Bond films, Bernard Lee. Sutherland’s segment even has a fleeting appearance by his fellow Canadian Al Mulock, who along with Woody Strode and Jack Elam was gunned down by Charles Bronson in the astonishing opening sequence of Sergio Leone’s masterpiece Once Upon a Time in the West (1968).

Sutherland also featured in 1960s British TV, most memorably in 1967 when he played a villain in an episode of the surreal and stylish espionage series The Avengers (1961-69) called The Superlative Seven. This has Patrick Macnee’s debonair John Steed being invited to a bizarre fancy-dress party on board a private jet plane, which, after it takes off, is discovered to be remote-controlled. Eventually, the plane lands Steed and the other, equally-baffled guests on a seemingly deserted island. There, the party start to be murdered one by one. As well as riffing on Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (1939), the episode has a science-fictional sub-plot where Sutherland attempts to create a race of super-soldiers. And the guest cast includes Charlotte Rampling and Brian Blessed before they became famous too.

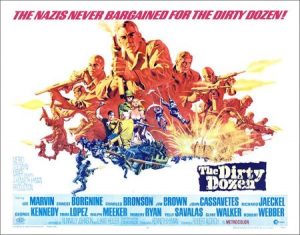

That same year, Sutherland turned up in Robert Aldrich’s loud, raucous and violent war movie The Dirty Dozen, about 12 convicts trained by the US Army and sent to France on a suicide mission against the Wehrmacht prior to the D-Day Landings The movie contained so many famous actors playing characters who weren’t among the 12 convicts – Lee Marvin, Ernest Borgnine, Richard Jaeckel, George Kennedy, Ralph Meeker and Robert Ryan – that, over the years, folk have become confused about who actually played the Dirty Dozen. I’ve even heard a few people declare that, with Sutherland dead, that’s all the Dozen gone. Well, no – because actors Stuart Cooper and Colin Maitland, who played two more of the Dozen, are still on the go.

© Kenneth Hyman Productions / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

The Dirty Dozen’s success led to Sutherland being cast in more World War II movies. Most notable of these was 1970’s Kelly’s Heroes, in which Clint Eastwood’s Private Kelly, a soldier in an American platoon in 1944 France, learns there’s a fortune in Nazi gold stashed in a bank behind enemy lines and persuades his fellow soldiers, including Sutherland and Telly Savalas, to help him steal it. Sutherland’s character is a loopy tank commander called Oddball who, with a blatant disregard for historical authenticity, was added to the script to satirise the then-ubiquitous hippy movement. He says spaced-out things like, “Don’t hit me with those negative waves so early in the morning!” or, “Woof, woof, woof! That’s my other dog imitation.” I suspect that for people my age – well, males my age – in the UK, Oddball is the character we’ll remember Sutherland best as, because British TV seemed to show Kelly’s Heroes every other week when we were kids.

Sutherland was also in 1976’s The Eagle Has Landed, playing an IRA man who aids some German commandoes, headed by that well-known German, Michael Caine, on a mission in England to assassinate Winston Churchill. Of Sutherland’s performance, the best that can said is that there are non-Irish actors who’ve played Irishmen with worse Irish accents.

Another war movie was M*A*S*H (1970), Robert Altman’s scabrous black comedy set during the 1950s conflict in Korea, in which Sutherland played insolent and rebellious US Army surgeon Hawkeye Pierce. The film won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, was the third-most popular movie of its year and gave Sutherland iconic status. I have to say that, though I like Robert Altman’s movies generally, M*A*S*H has not aged well. Today, much of its humour feels juvenile and mean-spirited, especially when directed towards Sally Kellerman’s Major Houlihan character, rather than ‘anti-establishment’, which it was hailed as at the time. Altman famously loathed the M*A*S*H TV show that was spun off from his movie and ran from 1972 to 1983, but I suspect time has been kinder to its gentler brand of humour.

© Casey Productions / Eldorado Productions / British Lion Films

Afterwards, Sutherland was in prestigious films like Alan J. Pakula’s Klute (1971), Fellini’s Casanova (1975) and Bernard Bertolucci’s 1900 (1975) – none of which I’ve seen. But it’s in Nicolas Roeg’s masterly horror film Don’t Look Now (1973) that, of his movies I have seen, I believe he does his best work. Don’t Look Now is an adaptation of a Daphne du Maurier story in which a grief-stricken couple try to get over the death of their daughter by immersing themselves in a restoration project in Venice – only to be haunted by sightings of a small figure in a red coat who at least resembles their deceased daughter. The film has two set-pieces at its beginning and end whose emotional impact has rarely been matched in the horror genre – Sutherland features heavily in both. Films about the supernatural, despite focusing on death, memories of the departed and the possibility of an afterlife, don’t usually capture the feeling of grief that well. But the pained, brittle performances by Sutherland and his co-star Julie Christie convey it with extreme poignancy. With their performances augmented by Nicolas Roeg’s camerawork, visual imagery and memorably-elliptical approach to storytelling, Don’t Look Now is a film for the ages.

Though for me Don’t Look Now gives Sutherland his best role, it’s Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) that gives him his best image. This is Hollywood’s second adaptation of Jack Finney’s novel The Body Snatchers (1955), wherein a low-key invasion of earth is staged by alien pod-people who gradually replace all the real people. The image in question, now a popular meme, comes in the final moments when Sutherland, the film’s hero, reacts to another character by pointing at her, adopting a grotesque, gawking expression and emitting an inhuman squeal. This tells us the pod-people have now replaced him too. The original Body Snatchers movie, made by Don Siegel in 1956, was set in small-town America, but Kaufman’s version audaciously shifts the action to San Francisco, and the result is just as good. Actually, I was going to say filmmakers have treated Finney’s novel well, for in 1993 Abel Ferrara directed another version that was decent too. But then I remembered there was a fourth version made in 2007 with Nicole Kidman and Daniel Craig, and it was rubbish.

© Solofilm / United Artists

As he grew older, Sutherland’s work in films and television inevitably saw him shift from being a leading man to being a grizzled character actor and then an esteemed ‘elder-statesman’ guest-star. His movies included star-laden Oscar-bait (1980’s Ordinary People), daft Alistair Maclean adaptations (1979’s Bear Island), slightly less daft Ken Follett adaptations (1981’s Eye of the Needle), overripe John Grisham adaptations (1996’s A Time to Kill), overstuffed British flops (1985’s Revolution), Sylvester Stallone movies (1989’s Lock Up), Clint Eastwood movies (2000’s Space Cowboys), paranoid Oliver Stone conspiracy thrillers (1991’s JFK), preposterous Roland Emmerich disaster movies (2022’s Moonfall) and Emma Thompson-scripted Jane Austen costume-dramas (2005’s Pride and Prejudice).

He made three films with his son Kiefer – who, when I first saw him onscreen in the 1980s, made me think, “Wow, he looks just like his dad!” – the afore-mentioned A Time to Kill, plus 1983’s Max Dugan Returns and 2015’s Forsaken. And he featured in four Hunger Games movies (2012-15), playing Snow, the despot running the future North American territory of Panem. I haven’t seen any of the Hunger Games series, but a future dystopian America ruled by a president called Donald sounds terrifyingly prescient.

Ironically, in the 1990s, Sutherland returned to his 1960s roots and started making horror movies again. He was in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1992), a clodhopping film that a few years later led to a sublime TV show; 1994’s The Puppet Masters, based on a short story by Robert Heinlein, which was a low-budget but not unenjoyable retread of Invasion of the Body Snatchers; 1998’s police-occult thriller Fallen, in which he rubbed shoulders with Denzel Washington and John Goodman; and 1999’s Virus, an Alien rip-off set on board a ship, in which Sutherland’s over-the-top villain is one of the few redeeming features – his old seadog is so sea-doggish he only lacks a pegleg and a parrot on his shoulder. Horror-adjacent is his role as Ronald Bartel in Ron Howard’s Backdraft (1991). He’s an incarcerated pyromaniac whom William Baldwin and Robert De Niro’s firemen-investigators turn to for help when they’re trying to catch the person responsible for a series of deadly, fiery arson attacks. Thus, he’s the Hannibal Lector of the fire-raising world.

However, while I write this, the Donald Sutherland performance that keeps coming to mind – accompanied by the lovely, plaintive song that accompanies it – is the one he essayed in the video for Kate Bush’s single Cloudbusting (1985). He’s a kindly inventor who creates a rainmaking machine, only to be taken away by some sinister men in suits, who obviously believe there are things man was not meant to know. This rather vitiates the song’s optimistic lyric, “Ooh, I just know that something good is gonna happen…” It’s left for Sutherland’s son, played by Bush, to complete his work. I visited the video on YouTube the other day and was touched to discover how the comments below were packed with people paying tribute to Sutherland.

© EMI