From en.wikipedia.org

This evening is Burns Night, marking the 261st anniversary of the birth of Scotland’s greatest poet, and one-time ploughman, Robert Burns.

In a normal, pandemic-free year, children in schools the length and breadth of Scotland would have spent the past few days standing in front of their classmates and teachers reciting Burns’ poems. Those poems, of course, were written in the Scots language; so this must be the only time in the year when kids can come out with certain Scots words in the classroom without their teachers correcting them: “Actually, that’s not what we say in proper English…”

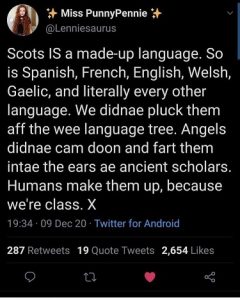

In fact, lately, Scots has been getting attention that has nothing to do with tonight being Burns night. Scots-language poetess Miss PunnyPennie has won herself tens of thousands of fans in recent months with her tweets and YouTube videos, in which she recites her poems and discusses a different Scots word each day. Those fans include author Neil Gaiman, comedienne Janey Godley and actor Michael Sheen.

Unfortunately, she’s also had to put up with a lot of negativity. She was the subject of a condescending and mocking piece published recently in the Sunday Times, which added insult to injury by calling her a blatherskite (‘ill-informed loudmouth’) in its headline. More seriously, she’s received much trolling on twitter. For instance, political ūber-chancer George Galloway – currently trying to reinvent himself as a diehard British nationalist in a bid to get elected to the Scottish parliament – tweeted something derogatory about her, in the process exposing her to potential abuse from his nutjob twitter followers.

Actually, Scots seems to have become part of the culture wars being waged in Scotland at the moment. Pro-United Kingdom, anti-Scottish independence zealots like Galloway hate the idea that Scottish people might have their own language because it contradicts their narrative that everyone on the island of Great Britain is one people and culturally the same. Hence, much online protestation (by people whose profiles are slathered with Union Jacks) that Scots is just ‘an accent’ or ‘slang’ or ‘a made-up language’ or ‘normal English with spelling mistakes’.

From cheezburger.com

Anyhow, as promised, here’s my next selection of favourite Scots words, those starting with the letters ‘D’, ‘E’ and ‘F’.

Dander (n/v) – stroll. Over the centuries, a lot of Scots words made their way across the Irish Sea to the north of Ireland, where I spent the first 11 years of my life, and the delightful word dander is one of them. I heard as many Northern Irish folk announce that they were ‘goin’ fir a dander’ as I heard Scottish folk announce it later, after my family had moved to Scotland.

Deasil (adv) – a Gaelic-derived word that means ‘clockwise’. It’s a less well-known counterpart to the Scots word widdershins, meaning ‘anti-clockwise’. I suspect the latter word is better known because it figures heavily in witchcraft and there’s been at least one journal of ‘Magick, ancient and modern’ with ‘Widdershins’ as its title.

Deave (v) – to bore and sicken someone with endless blather. For example, “Thon Belfast singer-songwriter fellah Van Morrison is fair deavin’ me wi his coronavirus conspiracies.”

Dicht (n/v) – wipe. Many a dirty-faced youngster, or clarty-faced bairn, in Scotland has heard their mother order them, ‘Gie yer a face a dicht’.

Doonhamer (n) – a person from Dumfries, the main town in southwest Scotland. For many years, I had only ever seen this word in print, not heard anyone say it, and I’d always misread it as ‘Doom-hammer’, which made me think Dumfries’ inhabitants must be the most heavy-metal people on the planet. But then, disappointingly, I realised how the word was properly spelt. Also, I discovered that the word comes from how Dumfries folk refer to their hometown whilst in the more populous parts of Scotland up north, for example, in the cities of Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Dundee. They call it doon hame, i.e. ‘down home’.

Dook (n/v) – the act of immersing yourself in water. Thus, the traditional Halloween game involving retrieving apples from a basin of water using your mouth, not your hands, is known in Scotland as dookin’ fir apples.

Douce (adj) – quiet, demure, civilised, prim. My hometown of Peebles is frequently described as douce. However, that’s by outsiders, short-term visitors and travellers passing through, who’ve never been inside the public bar of the Crown Hotel on Peebles High Street on a Saturday night.

From unsplash.com / © Eilis Garvey

Dreich (adj) – dreary or tedious, especially with regard to wet, dismal weather. A very Presbyterian-sounding adjective that, inevitably, is much used in Scotland.

Drookit (adj) – soaking wet. How children often are on Halloween after dookin’ fir apples.

Drouth (n) – a thirst. Many an epic drinking session has started when someone declared that they had a drouth and then herded the company into a pub to rectify matters. Its adjectival form is drouthy and Tam O’Shanter, perhaps Burns’ most famous poem, begins with an evocation of the boozing that happens when ‘drouthy neebors, neebors meet.’ Indeed, Drouthy Neebors has become a popular pub-name in Scotland and there are, or at least have been, Drouthy Neebors serving alcohol in Edinburgh, St Andrews, Stirling and Largs.

From Tripadvisor / © Drouthy Neebors, Largs

Dunt (n / v) – a heavy but dull-sounding blow. It figures in the old saying, “Words are but wind, but dunts are the devil,” which I guess is a version of “Sticks and stones will break your bones, but names will never hurt you.”

Dux (n) – the star pupil in a school.

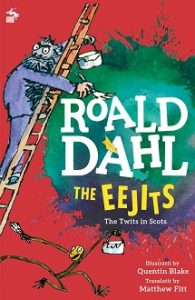

Eejit (n) – idiot. Inevitably, in 2008, when Dundonian poet Matthew Fitt got around to translating Roald Dahl’s 1980 children’s book The Twits into Scots, he retitled it The Eejits. Actually, there’s a lot of other Scots words in the D-F category that mean ‘idiot’. See also dafty, diddy, doughball and dunderheid.

© Itchy Coo

Eeksie–peeksie (adj/adv) – equal, equally, evenly balanced. A quaint term that was recently the subject of one of Miss PunniePenny’s ‘Scots word of the day’ tweets.

Fankle (n/v) – tangle. I’ve heard the English plea to someone to calm down, “Don’t get your knickers in a twist!” rephrased in Scots as “Dinna get yer knickers in a fankle!”

Fantoosh (adj) – fancy, over-elaborate, a bit too glammed-up.

Fash (v) – to anger or annoy, commonly heard in the phrase “Dinna fash yerself”. Like a number of Scots words, this is derived from Old French, from the ancestor of the modern French verb ‘fâcher’.

Feart (adj) – scared. During my college days in Aberdeen in the 1980s, on more than one occasion, I had to walk away from a potential confrontation with Aberdeen Football Club soccer casuals. the juvenile designer football hooligans who seemed to infest the city at the time. And I’d have the scornful demand thrown after me: “Are ye feart tae fight?!” Meanwhile, a person who gets frightened easily is a feartie.

Fitba (n) – football.

Flit (n/v) – the act of moving, or to move, house. Commonly used in Scotland, this verb has had success in the English language generally, as is evidenced by the use of ‘moonlight flit’ to describe moving house swiftly and secretly to avoid paying overdue rent-money.

Flyte (v) – to trade insults in the form of verse. This combative literary tradition can be found in Norse and Anglo-Saxon cultures, but flyting was made an art-form in 15th / 16th-century Scotland by poets like William Dunbar, Walter Kennedy and Sir David Lyndsay. There’s a poetic account of one flyting contest between Dunbar and Kennedy that’s called, unsurprisingly, The Flyting of Dumbar and Kennedie and consists of 28 stanzas of anti-Kennedy abuse penned by Dunbar and another 41 stanzas of Kennedy sticking it back to Dunbar. According to Wikipedia, this work contains “the earliest recorded use of the word ‘shit’ as a personal insult.” Thus, flyting was the Scottish Middle-Ages literary equivalent of two rappers dissing each other in their ‘rhymes’; and Dunbar and Kennedy were the Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls of their day.

Footer (v) – to fumble clumsily. I remember reading a Scottish ‘coming of age’ story – though I can’t recall its title or author – in which the inexperienced hero footered haplessly with a young lady’s bra-clasp.

Favourite Scots words starting with ‘G’, ‘H’ and ‘I’ will be coming soon.

From unsplash.com / © Illya Vjestica