From unsplash.com / © Dalila Moreira

For the first time in years, I’ve been reminded that the sport of snooker still exists. This is because of the headlines that have accompanied the final of the 2025 World Snooker Championship, which a few days ago was won for the first time by a Chinese player, Zhao Xintong. His victory has led to speculation that snooker, already popular in China, will rise to ‘another level’ there. Mind you, this new association with China will probably cause Donald Trump to slap tariffs of 145% on all snooker-related imports to the USA.

Anyway, snooker being in the news again has prompted me to dust down and repost this nostalgic piece about the long-ago days when snooker was exciting, all the time…

I learned many things from my maternal grandmother before she passed away in 1997 at the venerable age of 93. One of them was a fascination with the late 1970s / early 1980s phenomenon that was televised snooker.

During the 1970s most of my family, immediate and extended, had lived in Northern Ireland. In 1977, however, my parents bought a small farm in the south of Scotland and that became the new home for them, me and my siblings. My grandmother, then in her seventies, soon got into the habit of crossing the Irish Sea and visiting us in Scotland. However, because of the distance and effort involved in travelling, she would make the most of it and stay for a few weeks at a time.

Since my grandmother was an avid viewer of TV programmes, this meant that, while she resided in our house, we had to relinquish control of our television set to her. Unfortunately for me, she seemed addicted to every soap opera going, from the humble British ones like Coronation Street (1960-present), Crossroads (1964-88) and Emmerdale Farm (1972-present) to the opulent American ones like Dallas (1978-91) and Dynasty (1981-89), all of which I considered to be televisual brain-death.

However, one unexpected thing I noticed when she came to stay was that she was also a big fan of the sport of snooker, which had recently taken off in popularity and was attracting big TV audiences. At some point, I started watching it with her, with the result I became hooked on it too for a few years.

Here’s an example of how much my grandmother was into the snooker. One time she arrived with us while the World Snooker Championship – sponsored until 2005 by the tobacco company Embassy – was underway and was being broadcast live on BBC2. Some matches took place early in the morning, so she’d rise early to watch them. One morning my mother entered the living room, where my grandmother was immersed in a TV snooker game, and noticed she was wearing a cardigan that was inside out. A label protruded from the knitted collar behind her neck. My mother pointed this out, but she just sighed and nodded at the TV screen. “I can’t take it off and change it round just now,” she said. “If I did, I’d cause bad luck for Alex.”

From wikipedia.org / © Bigpad

The Alex she worried she might inflict bad luck on if she put her inside-out cardigan on the right way was Alexander Gordon Higgins, ‘Hurricane’ Higgins as he was known to snooker fans. He was famed for his mercurial abilities. On a good day he’d play brilliantly. On a shit day he’d play… well, shit. He was also famed for his mercurial temperament, which I’ll talk about in a minute. He was of working-class Protestant stock from Belfast in Northern Ireland, which was one of the reasons why my grandmother loved him. I remember a couple of times watching TV with her when Higgins fluffed an important shot. “Oh Alex!” she’d lament. “Alex, Alex, Alex, Alex…”

As snooker had risen to prominence, so had Higgins. He’d been playing from the age of seven, first in Belfast’s Jampot Club and YMCA; and by 1968, before he turned 20, he’d won the All-Ireland and Northern Ireland Amateur Snooker Championships. Physically slight, Higgins had for a time in the 1960s intended to become a jockey rather than a professional snooker player. I suspect this was part of the spell he cast later over my grandmother and ladies of a similar age, when he was still scrawny and undernourished-looking. Those ladies just wanted to feed him up and put some colour in his cheeks.

By 1972, Higgins had turned professional and he won that year’s World Snooker Championship, although this didn’t make much of a stir in the public consciousness because technology wasn’t ready for the sport yet. As the game required its players to sink all the red balls on the table, and then pocket in order the yellow, green, brown, blue, pink and black ones, you needed to watch it on a colour television to know what was going on. And in British homes, colour TV sets didn’t outnumber black-and-white ones until 1976. I remember an uncle acquiring a colour TV before 1976, but the colours refused to be contained by the outlines on the screen and would swim across them, which made it migraine-inducing to watch.

However, once everyone could watch snooker in proper colour, the sport took off and its leading players became stars. What’s fascinating, and retrospectively rather sad, is that many of those guys weren’t cut out to be stars. They didn’t have the glitz of other big British sporting names of the 1970s, such as elegant playboy racing driver James Hunt or permed heartthrob footballer Kevin Keegan. Often, they’d grown up learning to play snooker in the booze-sodden, cigarette-fogged environments of pubs and club and hadn’t received much of a formal education. From the way Higgins behaved at the snooker table and away from it, you sometimes wondered if he’d had any opportunity to develop social skills at all. It must have been discombobulating for them to suddenly find themselves in the national limelight, suddenly become big media names and suddenly be chasing big sums of prize money.

Among this collection of misfits, oddballs and eccentrics there was, besides Higgins, Welshman Ray Reardon, already in his forties when snooker made him famous. Not one to modify his appearance and style to match the expectations of stardom, Reardon sported an imposing widow’s peak; and that and the way he stalked hungrily around the table earned him the nickname of ‘Dracula’. Then there was the ashen-faced Jimmy ‘Whirlwind’ White of Tooting, London, who wasn’t yet out of his teens by the end of the 1970s, who slightly resembled Johnny Depp in his Edward Scissorhands period and who came across as a younger, marginally less troubled version of Higgins. From the age of eight or nine, he’d played truant from school so he could practise in his local snooker hall.

© ITC Entertainment

Jimmy ‘Whirlwind’ White and Ray ‘Dracula’ Reardon, incidentally, inspired an odd little movie called Billy the Kid and the Green Baize Vampire (1987) directed by the much-admired Alan Clarke. The title characters, obviously modelled on White and Reardon, were played by Phil Daniels and Alun Armstrong. The film has received the accolade of being ‘undoubtedly the only vampire snooker musical in cinema history.’

Another unconventional figure was Higgins’ fellow Northern Irishman Dennis Taylor, who suffered from bad eyesight. Ordinary glasses weren’t much use to Taylor at the snooker table because, when he bent over it to take a shot, his weak eyes would end up looking over the top of the glasses rather than through them. So he had to wear a pair of specially designed glasses with heightened lenses that made him resemble a non-spangly incarnation of Elton John.

From wikipedia.org / © John Dobson

Meanwhile, some glamour was injected into the snooker world by the Latin-looking, vaguely Antonio Banderas-esque Silvino Francisco, who was actually South African; and by the white-clad Kirk Stevens, a handsome lad with the all-important 1970s perm, who hailed from Toronto.

Stevens was one of a triumvirate of Canadian players who found fame as snooker players back then, which meant it was the first, possibly only, time that your average British person on the street could name three famous Canadians off the top of their heads. Also from Canada was Cliff Thorburn, who was known as ‘the Grinder’ for his remorselessly methodical style of play and who resembled a better-groomed Donald Sutherland; and Thorburn’s fellow British Columbian ‘Big’ Bill Werbeniuk, whose weight was in the region of 20 stones. The hefty Werbeniuk suffered from a tremor and to subdue this when playing he relied on beer: lots of beer. According to his Wikipedia entry, he’d typically have knocked back six pints before the start of a match and he could get through 40 to 50 pints in a day. One urban myth at the time was that Werbeniuk had all this beer medically prescribed to him by a doctor and got it for free. More feasible was a story in the British press about him claiming the price of half-a-dozen pints each match-day as a tax-deductible expense.

Thus, snooker back then offered an array of peculiar characters whom you’d find in few other sports, constantly having their ups and downs, which I imagine was another reason why it appealed to my soap-opera-mad grandmother.

Some of the downs they suffered were spectacular. In his autobiography, Jimmy White confessed to taking crack cocaine for a few mad months in the 1980s, while Kirk Stevens owned up to having a general cocaine problem during the same period. Stevens’ admission came after the final of the 1985 British Open, in which he’d played Silvino Francisco. The South African accused Stevens of being as ‘high as a kite’ during the match. Not that Francisco could complain too much, for in 1997 he was arrested and jailed for three years for smuggling cannabis with a street value of £155,000.

In the late 1980s Cliff Thorburn was heavily fined and banned from a couple of tournaments for failing a cocaine test; and to complete the Canadian drugs hat-trick, Bill Werbeniuk quit the sport after getting into trouble for taking the drug Inderal, which snooker’s governing body listed as a forbidden substance. To be fair to Werbeniuk, he was taking Inderal on the advice of his doctors, who thought it might help to curb his ruinous alcohol consumption.

Alex Higgins, meanwhile, was in a league of his own. An unabashed pisshead, he somewhat inevitably ended up in the orbit of the hellraising movie star Oliver Reed. However, if you’re to believe some of the stories, Reed found him hard to put up with – and vented his frustrations by, for instance, chasing Higgins around his mansion with an axe and feeding him a pretend hangover cure made out of perfume and washing-up liquid. Neither was Higgins afraid of drugs. According to fellow snooker-player John Virgo, he once asked clean-living popstar Sting at a concert if he had any ‘gear’. “Yes,” said Sting, “we’ve got some baseball caps and T-shirts left.” “No,” retorted a disgusted Higgins. “Not that kind of gear. I mean the kind of gear that goes up your nose!”

Higgins logged up a long and unflattering list of misdemeanours. He got into trouble for pissing into a potted plant during a tournament in 1982. (Virgo: “As he later argued, they were fake plants in the pot, so he ‘wasn’t being cruel to the flowers’”). He headbutted a tournament director in 1986 after refusing to provide a urine sample for a drugs test. He ended up playing in the 1989 European Open on crutches and with an ankle in plaster after falling 25 feet from a ledge outside the windows of his girlfriend’s apartment – he’d been trying to climb into the apartment after having a row with her. He punched a press officer in 1990. And the same year, he threatened to have the mild-mannered Dennis Taylor shot, which was no laughing matter since Higgins and Taylor belonged to either side of Northern Ireland’s sectarian divide and Higgins came from Belfast’s Sandy Row area, notorious for its links with the Protestant paramilitary Ulster Defence Association.

The result was a slow, painful but inevitable erosion of Higgin’s playing ability, his emotional stability, his finances and his popularity. By the late 1990s, I couldn’t argue when an Irish friend dismissed him out of hand as ‘an unmannerly wee pup.’

From wikipedia.org / © Joni-Pekka Luomali

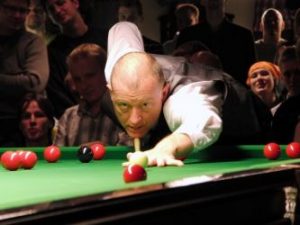

Even before those characters began to self-implode amid booze, drugs and violence, the future of snooker had materialised in the form of Englishman Steve Davis. He would dominate the sport during the 1980s, when he won six world titles and was ranked world number one for seven years in a row. Davis was scandal-free in his behaviour but also, unfortunately, relentlessly robotic in his playing style and deadly dull in his personality. It was no surprise when the satirical TV puppet show Spitting Image (1984-96) featured a sketch where Davis tries to jive up his image by giving himself a new nickname, to rival Alex Higgins’ ‘Hurricane’ and Jimmy White’s ‘Whirlwind’. Eventually, he chooses ‘Interesting’.

Steve ‘Interesting’ Davis, in effect, created the mould for the snooker players who would follow. A new generation of them were growing up, less conditioned by the boozy, seedy world of pubs and clubs from which many of their predecessors had emerged. They were better equipped to withstand the pressure of public and media attention and go sensibly about the business of winning tournaments and making money. For these pragmatic types, snooker was more of a job than an obsessive passion.

Still, some of my fondest snooker memories come from seeing the seemingly invulnerable Davis get beaten in a crucial game by a less organised, more human opponent. There was, for example, the final of the UK Championship in 1983 when Davis went up against Higgins and soon had a seven-frames-to-nil advantage. Miraculously, Higgins managed to pull himself together and eventually beat Davis 16-15 to win the competition.

Even better was the 1985 World Championship where Davis played Taylor and again built up a seemingly unassailable early lead, of eight frames to nil. But Taylor rallied and the lead seesawed between them, and eventually both players ended up on 17 frames each. Late on in the deciding frame, victory was decided by whoever could pocket the black first – which Taylor managed to do. My jubilation at Taylor’s win was marred by the fact that I and many others were watching the final that night in the Hillhead Bar at Aberdeen University’s Hillhead Halls of Residence. The final frame went on beyond midnight and beyond the bar’s closing time. Desperate to get us all out of the place, some absolute sadist in the bar-staff pulled the plug on the TV seconds before Taylor took that final, all-important shot at the black.

I’ve written humorously about them, but things didn’t end well for some of those snooker players. Kirk Stevens returned to Canada where, broke, he had to eke a living as a construction worker, landscape gardener, lumberjack and car salesman before he finally got back onto the local snooker circuit. Silvino Francisco, before the nadir of his cannabis arrest, was already in an ignominious situation, having to earn cash by working in a mate’s fish-and-chip shop. Bill Werbeniuk was unemployed and on disability benefits prior to his death in 2003.

From wikipedia.org / © The Royal Bar

Higgins’ end was pitiful. Diagnosed with throat cancer in 1998, and subjected to radiotherapy treatment that destroyed his teeth and made it difficult for him to eat even the meagre amounts of food that he’d survived on previously, Higgins refused to curtail his heavy drinking and smoking. In 2010, having become dependent on disability payments just as Werbeniuk had, Higgins was found dead in his Belfast flat. His demise was attributed to a mixture of malnutrition, pneumonia and bronchitis. Photographs of him taken towards the end of his life show a shrivelled, shrunken figure that looked more like Dobby the House Elf from the Harry Potter movies than a human being. I’m relieved my Hurricane-loving grandmother didn’t live long enough to see him in such a state.

With nearly all its old characters retired or dead, I’ve paid little attention to the snooker world in the last quarter-century. Indeed, looking at recent lists of champions, the only names I recognise are those of Ronnie O’Sullivan and John Higgins (who’s no relation to Alex). Still, for its modern players, it’s no doubt a saner and safer, though blander, sport nowadays.

But one nice thing I’ve noticed is that Steve Davis, once the embodiment of everything I found mind-numbingly boring about snooker, is actually quite cool nowadays. Since hanging up his snooker cue, he’s reinvented himself as a radio, club and festival DJ specialising in trancey, dancy electronic music. He collaborates with British-Iranian musician and composer Kavus Torabi and they’ve even formed an electronica band called the Utopia Strong, which released albums in 2019 and 2022.

So it turns out that Davis got it right with his tactics. He came across as a clean-living dullard in his youth but crucially he preserved his faculties, health and finances. And now, in his snooker retirement, he’s become Steve ‘Interesting’ Davis at last.

From wikipedia.org / © Steve Knight