The passage of time is a strange and frightening thing. When they first got airplay on Britain’s Radio 1, the three members of the indie-pop-punk-rock band Ash were still at school in Downpatrick, Northern Ireland. At that point the combined ages of their three members, vocalist and guitarist Tim Wheeler, bassist Mark Hamilton and drummer Rick McMurray, must have added up to a number in the low 50s, similar to (perhaps less than) the average age of a member of the Rolling Stones back then. In other words, they seemed stupendously young to me.

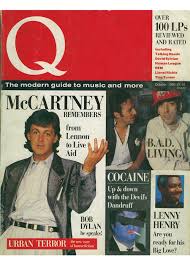

So, it was a shock when I went to see Ash perform at Singapore’s Hard Rock Café last Friday night and discovered that suddenly all three are now well into their 40s. How did that happen? Surely, it was only a few months ago that I bought their first album after reading a good review of it in Q magazine?

But actually, that was back in 1996. Where does the time go?

I think it was also in the now-defunct Q magazine, in the 1990s, that I read how Ash were rumoured to be the favourite band of a young Prince William. Well, it has to be said that Ash in 2024 have weathered the years rather better than their royal fan, who these days is first in line to the throne. Unlike the follicly-challenged Prince William, Wheeler and Hamilton still have full heads of hair – although, suspiciously, McMurray sported a baseball cap throughout the gig.

The many Western expats present in tonight’s audience looked of a similar vintage to Ash and Prince William — teenagers back in the 1990s but now middle-aged. Incidentally, the crowd also contained a fair sprinkling of Singaporeans. From what I can gather, this was Ash’s fourth visit to the city-state, so they’d evidently acquired a few local fans too.

Tonight was the first time I’d attended a gig in the Hard Rock Café. I’m not a fan of this particular dining franchise, though I have to admit they did a good job of transforming it from a restaurant to a concert venue – a venue with an old-fashioned ‘small, sweaty club’ vibe, which was especially welcome in Singapore, where too often you have to watch bands in sedate, sit-down establishments, stuck among endless rows of seats, unable to move about and shake a leg. The café could have done with a higher stage, however. I felt sorry for the shorter Ash fans. Jammed behind taller folk, probably all they could see of the band were the tops of Wheeler and Hamilton’s still-hirsute heads.

One other feature of the Hard Rock Café I wasn’t thrilled by was its bar prices. A small glass of Carlsberg beer cost 14 dollars, which meant you’d be paying in the region of 30 dollars for something approximating a pint, a costly sum even by Singapore’s standards. Presumably because the café wanted to do some normal Friday-evening business beforehand, Ash didn’t come onstage until ten o’clock, with the doors opening for the gig at nine. I arrived shortly after nine, saw the prices, popped out again and headed along the street to the craft-brewery bar-and-restaurant Brewerkz, where a pint cost me a slightly less eye-watering 23 dollars.

When I returned to the café just before ten, it was mobbed. Since I wouldn’t see much of the band from the back, where the bar was, I decided to forego further boozing, burrowed my way through the crowd, secured myself a spot about two yards from the barrier before the stage, and stayed there for the show’s duration. Even there, my view wasn’t perfect – I saw Wheeler and Hamilton’s upper halves, though they often vanished when excitable people in front of me waved their arms in the air, and I needed to stand on tiptoe to see McMurray at his drumkit.

And mounted on the wall above my head was an example of the rock-and-roll memorabilia that famously decorates the Hard Rock Café franchise all over the world. This was the drumkit of Rob Blotzer, drummer with the 1980s hair metal band RATT. I’d completely forgotten about the dreadful, poodle-headed RATT until I saw that drumkit. But now I remember them again. Thanks for that, Hard Rock Café.

The omens were not good when Ash began the gig. Firstly, a forest of hands shot up around me, clutching smartphones, all filming, and I had a sickening premonition of being surrounded by dozens of tiny glowing screens, each showing a tiny glowing image of the band, for the next hour-and-a-half. Secondly, it quickly became obvious that there were sound problems, with Wheeler’s vocals almost buried by the noise of Hamilton’s bass. Thankfully, most of the phones were soon lowered again – the crowd had just wanted some footage of their heroes coming onstage – and, a few songs in, the sound-mix became more balanced.

And what followed was very enjoyable. The crowd, at least where I was, had fun and Ash looked like they were having a good time too. Unlike a number of bands I’ve seen at gigs in various parts of the world, this band gave the impression that they knew, and appreciated, where they were. For example, at one point, McMurray told the audience a funny anecdote from the previous time they’d played Singapore.

Also, due to the fact that I was standing near one of the main speakers, I was left partially deaf for the next 24 hours. Which was a pain in the arse at work the next day, but surely a sign that I’d been to a good gig.

The 40-something Ash fans in attendance must have found it a nostalgic treat, because half of the 18-song setlist came off the two hit albums of their early years, 1977 (1996) and Free All Angels (2001). These songs included Angel Interceptor, Goldfinger and Girl from Mars from the former and Shining Light, Burn Baby Burn and Sometimes from the latter. Oh, and the famously Jackie Chan-referencing Kung Fu from 1977 got an airing too. (I’m sure Ash were delighted when Kung Fu actually got used in a Jackie Chan movie, playing during the bloopers reel at the end of 1995’s Rumble in the Bronx.) To give proceedings a slightly more up-to-date feel, they also played three tracks from their most recent album, 2023’s Race the Night. When, between songs, Wheeler mentioned the album they’d ‘recorded last year’, an Ash fan behind me remarked in a loud and serious voice: “Surprisingly good!” So maybe I should check it out.

Alas, the Ash album I like best – the guitar-heavy Nu-clear Sounds (1998), which was released between 1977 and Free All Angels, got a mixed reception from the critics and had disappointing sales – was represented by just one song tonight, Wildsurf. I would have loved to hear them play more songs off it, especially the singles Jesus Says and Numbskull, which I think are cracking tunes. The same thing happened last November when I went to see the Manic Street Preachers (they played only one song from my favourite Manics album, 1993’s Gold Against the Soul) and Suede (ditto for my favourite Suede album, 1994’s Dog Man Star). Maybe this is a quaint Singaporean curse I’ve fallen victim to.