From pixabay.com / © Benjamin Balazs

It’s that time of year again – October 31st, Samhain, All Hallow’s Eve, Halloween.

As is customary on this blog, I’ll mark the occasion by displaying ten items of creepy, frightening or unsettling artwork that, during the past year, I’ve stumbled across in my Internet wanderings and taken a shine to. And this time, I’ll feature a few pictures that aren’t just dark in tone but actually relate to Halloween.

So, to set the mood, here’s a picture called Halloween by the Ohio artist Maggie Vandewalle who, her website explains, “has used watercolour or graphite to convey her love of the organic world and that of a really good story.” This has led to her producing many images of animals linked to the occult: cats, bats, crows, hares. She also does a good job of drawing trees, and I find this landscape particularly gorgeous. Few things are more evocative than looking at the colours of an evening sky through a mesh of darkening tree-branches.

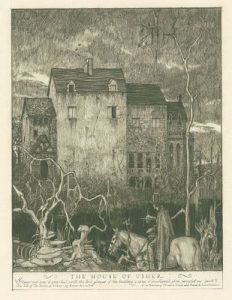

Earlier this month – October 7th – was the 175th anniversary of the death of America’s premier writer of macabre fiction, Edgar Allan Poe. Here’s something Poe-esque, an illustration for his story The Fall of the House of Usher (1839) by the New York-born, New Jersy-raised and Connecticut-dwelling writer and illustrator Robert Lawson. Lawson’s speciality was children’s books – his work adorns such classics as Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper (1881) and T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone (1938) – and as this gallery page for the Goldstein Lawson Collection shows, he had a flair for drawing fairy tale and mythological creatures. However, in 1931, he won an award for creating an etching for Poe’s famous tale of familial decline, madness and destruction. As my digital copy of the etching is murky and wouldn’t look good in the cramped confines of this blog, here’s the clearer, preliminary pencil-drawing Lawson made for it. As the late Roger Corman, director of the famous 1960 film version House of Usher, once commented, “The house is the monster.” It certainly looks it in this.

From feuilleton / © Estate of Robert Lawson

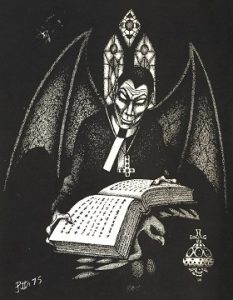

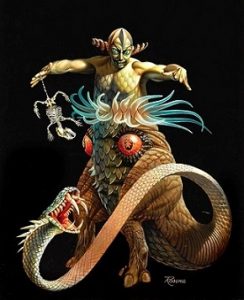

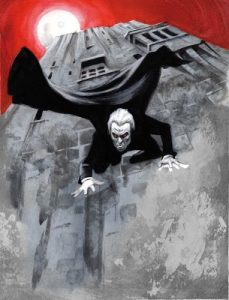

From Edgar Allan Poe to Bram Stoker. With yet another Dracula film adaptation, Roger Eggers’ Nosferatu, scheduled for release at the end of this year, I thought it timely to include this illustration featuring Stoker’s legendary vampire count by Spanish painter and illustrator Fernando Vicente. It depicts the scene where Dracula crawls down his castle wall, “face down with his cloak spreading out around him like great wings”, fingers and toes grasping “the corners of the stones”, descending “with considerable speed, just as a lizard moves along a wall.” In keeping with Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula is still an old man at this point – but Vicente’s version is an old man who looks like he can take care of himself and whom you wouldn’t want to mess with. Indeed, he makes me think of the late silver-haired American character-actor Dennis Farina, who specialised in playing tough mobsters and cops (and who’d been a Chicago police detective before taking up acting). Though it’s Dennis Farina with red eyes and fangs.

From bookpatrol.net / © Fernando Vicente

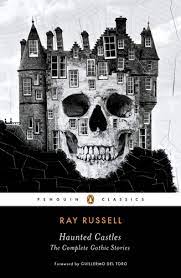

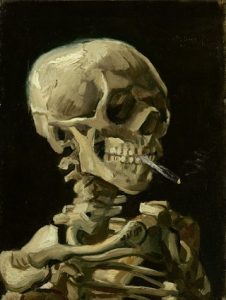

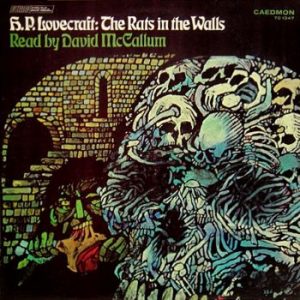

And from Bram Stoker to H.P. Lovecraft. Just over a year ago, the Scottish actor David McCallum – best known for his TV roles in The Man from UNCLE (1964-68), The Invisible Man (1975), Sapphire and Steel (1979-82) and NCIS (2003-23) – passed away. In the tributes that followed, there wasn’t much mention of the fact that McCallum was also a musician and writer. And nothing was said about his prolific career as an audiobook narrator, a career that extended to the weird, baroque and morbid world of legendary horror writer H.P. Lovecraft. Among the Lovecraft stories he narrated was The Rats in the Walls (which can be heard here on YouTube). I like this cover illustration from the original LP of the recording, designed by Brooklyn artists Leo and Diane Dillon, with its giant skull (composed of normal-sized skulls and other bones) and an insane green face, seemingly spewing yellow bile, emerging from the bottom of the wall behind. More on the Dillons can be found here and here – the latter site featuring some cracking cover art they did for the 1972 Ray Bradbury novel The Halloween Tree.

From pinterest.com / © Leo and Diane Dillon

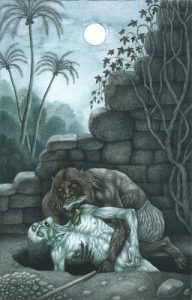

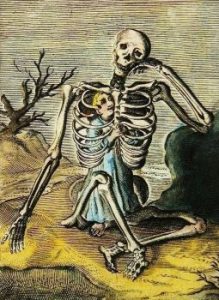

Old bones are also on view in this image, which I’ve seen called The Boy in the Skeleton on social media. It’s by the Dutch engraver and woodcutter Christoffel van Sichem the Younger, who lived from the late 16th to the mid-17th century. I presume the panic-stricken lad, inside the larger and rather insouciant-looking skeleton, serves as a metaphor for how the human soul is imprisoned within a cage of flesh and bone, despite that cage being a fragile and ultimately perishable one.

From x.com

Right, back to the theme of Halloween. I love this picture by the Paris-based illustrator Nico Delort. Entitled It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, it’s obviously inspired by the much-loved, animated TV Halloween special of the same name, which was based on the cartoon-strip creations of Charles M. Schultz and first broadcast in 1966. It shows the thumb-sucking, security-blanket-clutching Linus Van Pelt venturing into his local pumpkin patch to await the coming of the alternative Santa Claus, the Great Pumpkin. Linus can be discerned in the middle distance of Delort’s composition, while the Great Pumpkin – possibly – can be glimpsed on the end of a faraway cloud. But it’s the satanically-grinning pumpkins in the foreground that command your attention.

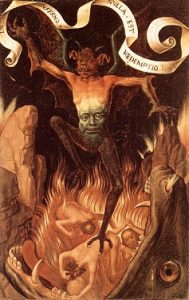

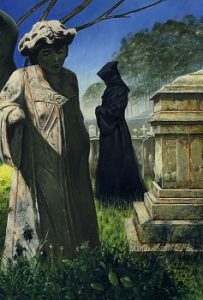

Also satanic is this picture by British artist Dave Kendall, who’s worked in collaboration with talents as diverse as Pat Mills (founder of the world’s greatest sci-fi comic, 2000AD), heavy metal titans Metallica and the late Lovecraftian author Brian Lumley. Among Kendall’s dark, brooding and frequently twisted creations, I find this one of the most disturbing. Its image of a bloody-faced nun, with grotesquely elongated fingers, is inspired by a short story called The Hands. This was penned in 1986 by the esteemed Liverpudlian horror writer Ramsey Campbell and can be read here.

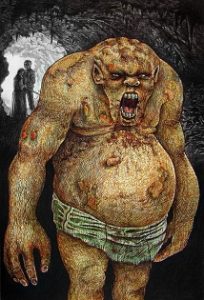

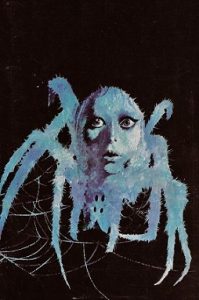

More female monstrosities are displayed in this picture. All I can determine about these bat-ladies is that they’re the work of an Austrian artist called Robert Loewe and appeared in the February 11th, 1913 edition of the weekly satirical magazine Die Muskete.

From thefugitivesaint.tumblir.com

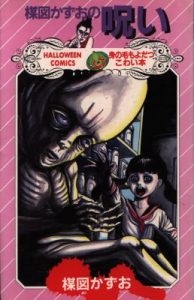

Meanwhile, it’s a female doing the screaming – in impeccable, wide-mouthed and wide-eyed Japanese manga style – on this cover illustration for the appropriately named Halloween Comics. The artist is Kazuo Umezo, known in Japan as ‘the god of horror manga’. For inspiration, Umezo has often drawn on traditional Japanese folklore and legends and he’s made this argument against the many people – parents, editors, educators – who’ve urged him to ‘think of the children’ and tone down the horror content of his work: “Old Japanese folk stories and fairy tales could be unflinchingly brutal. They come from a time when tragedy and carnage was an everyday part of life. Now we have people calling to water them down, which essentially whitewashes history. It’s insulting to the memory of those who suffered to bring us these stories.” More of Umezo’s work, definitely not toned down, can be viewed on this entry dedicated to him on the website Monster Brains.

From monsterbrains.blogspot.com / © Kazuo Umezu

Finally, to end things on a gentler note, here’s a picture I appreciate both as a cat-lover and as someone who finds graveyards fascinating – one of a cat (black, of course) exploring a graveyard at night. It’s from the cover of a ‘cozy mystery’ novel entitled Witch Way to Murder (2005) by Shirley Damsgaard and it’s by the New York artist Tristan Elwell. A more recent and better-known cover illustration by Elwell, which also involves a cat, is the one adorning John Scalzi’s bestselling and award-winning satirical novel Starter Villain (2023).

From unquietthings.com / © Tristan Elwell

Enjoy Halloween!