© Penguin Books

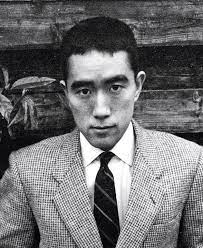

Anyone familiar with my wokey, lefty, liberal politics might be surprised to hear that I’m an admirer of the Japanese author Yukio Mishima. Indeed, I’d probably include his Sea of Fertility tetralogy – or at least, its first two entries, Spring Snow and Runaway Horses (both 1969) – among my top two-dozen novels of all time.

Yes, that’s Yukio Mishima, the ultra-right-wing Japanese nationalist who rejected democracy, formed his own militia, and in 1970 attempted to take over a military base in Tokyo while calling on the members of Japan’s Self-Defence Force to stage a coup and restore the Japanese Emperor to his former glory. And who, when it became clear that the attempted coup was a flop, committed seppuku, i.e., ritually disembowelled himself.

When I lived in Japan in the 1990s, I remember Japanese acquaintances who leaned leftwards in their politics wincing in horror when I said I liked Mishima’s books. One guy who was in his forties, and had been a ‘New Left’ student in the late 1960s, told me he’d been terrified when he first heard the news that Mishima was attempting a coup d’état. For a moment, he genuinely feared that Japan was going to end up under the heel of a right-wing, militaristic, Emperor-worshipping regime like the one that’d dominated the country in the 1930s and led it to disaster in the 1940s.

And I seem to remember reading an interview with the Japanese composer and occasional actor Ryuichi Sakamoto – now, alas, the late Ryuichi Sakamoto – in which he stated bluntly that he’d hated Mishima and was glad when he heard that he’d done himself in. This was despite Sakamoto supposedly basing his performance in the 1983 movie Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence on the author, and despite him titling the music he composed for the film Forbidden Colours, after Mishima’s 1951 novel of the same name.

I won’t deny that I find Mishima’s extreme politics as objectionable and doolally as the next person. (At least, the next sane person. In 1990s Japan, there were plenty of Uyoku dantai around, i.e., fascistic dingbats who prowled the streets in flag-emblazoned black vans, ranting and blasting patriotic music out of loudspeakers and generally making tits of themselves, and no doubt they thought Mishima’s ideas were wonderful.) But I can forgive him for his politics because I find his writing exquisite. That’s with a couple of exceptions. Forbidden Colours, a book I just could never get my head around, is one.

© Penguin Books

A friend and former colleague called Eiji Suenaga told me back then about the afore-mentioned Sea of Fertility novels and gave me some interesting advice about how to read them. Don’t, he said, try to read them until you’ve reached middle-age. Only at that stage in your life can you grasp their full significance and really appreciate them. Thus, I didn’t read them until I was in my forties. As I said, the first two in the series absolutely blew me away. However, the third novel, 1970’s The Temple of Dawn, gets rather bogged down with its copious musings on Buddhism, while the fourth and final one, the same year’s Decay of the Angel, feels slightly rushed and sketchy in comparison to its predecessors. Though to be fair to Mishima, he had rather a lot on his mind by then. It’s said that he penned Angel’s final lines on the morning of his suicide. (You can’t accuse Mishima of being a writer who talked the talk but didn’t walk the walk. I mean, he polished off his last novel in between attempting to overthrow his country’s government and ritually gutting himself… I couldn’t imagine Martin Amis doing that.)

One thing that makes Mishima an acquired taste is his bleak intensity. You don’t read his work if you’re looking for some laughs. Thus, in Confessions of a Mask (1949), you get a coming-of-age novel, an obviously autobiographical one, involving suppressed homosexuality and graphic, at times violent and macabre, sexual fantasies. In The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea (1963), you get a sect of young boys who quietly go Lord of the Flies, convince themselves they don’t have to abide by the rules of common morality, and start mutilating kittens – with the implication that soon they’ll be doing similar things to human beings. In The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956), you get a mentally-ill Buddhist acolyte setting fire to the titular temple, the Kinkaku-ji, in Kyoto – an act of arson that’d actually befallen that temple in real life in 1950.

Admittedly, Mishima’s 1954 novel The Sound of Waves is a nice, happy love story. During my Japan days, I noticed how popular it was among certain Westerners living there. I suspect they liked Waves because it allowed them to boast they’d read a book by one of their host-country’s most important 20th-century novelists – but it spared them having to grapple with that novelist’s normal, angsty, messed-up stuff. However, Mishima himself didn’t rate Waves highly. He once brutally dismissed it as ‘that great joke on the public’.

Well, I recently read Mishima’s 1968 novel Life for Sale and I now wonder if I should revise my ideas about him and the sort of literature he specialised in. It’s unlike anything I’ve read by him before. Unashamedly pulpy in content, wildly episodic in nature, quite outrageous in its plot-twists, the book often feels like Mishima wrote it with his tongue so far into his cheek that it’s a surprise the cheek didn’t burst. At times, it seems a million miles away from the gloom and seriousness of his other work. That’s ‘at times’, though. There are moments when the sombre, highbrow Mishima of old does resurface… But never for long.

It kicks off in the conventional Mishima style I’m familiar with. Page one has the hero, Hanio, attempting to commit suicide. He consumes “a large amount of sedative in the last overground train that evening. To be precise, he gulped it down at a drinking fountain in the station before boarding the train. And no sooner had he stretched out on the empty seats than everything went blank.” Mishima-esque too is the fact that Hanio is driven to this attempt on his own life by nothing of great significance: “Suicide was not something he had put much thought into. He considered it likely that his sudden urge to die arose that evening while he was reading the newspaper… he could only conclude that he had attempted to end It all on a complete whim.”

Hanio survives, however. With a rather more nihilistic mindset than before, he abandons his nine-to-five job and puts an advert in a newspaper: “Life for Sale. Use me as you wish. I am a twenty-seven-year-old male. Discretion guaranteed. Will cause no bother at all.” And that’s when the fun starts. The advert’s first reply comes from an embittered old man with a much younger and voluptuous wife. The wife is currently cuckolding him with a mobster. The old man hires Hanio – who now considers his life both meaningless and expendable – to seduce his wife and make sure that her mobster boyfriend finds them both ‘at it’: “When he claps eyes on you, you’re sure to be killed, and she’ll probably be dead meat too.” Hanio does as he’s told, but things don’t go according to plan. Someone gets killed, but not him.

He then proceeds to his next case. A librarian, “an utterly nondescript middle-aged woman… more like an elderly spinster, perhaps someone who taught English literature at a girls’ college of higher education,” involves him in a plot with some criminals, a rare book about Japanese beetles that’s housed in her library, and a particular type of beetle that supposedly can be ground down and made into a deadly poison. Hanio, with zero interest in remaining alive, is asked to act as a guinea pig for the newly-manufactured poison. He agrees, but again the unexpected happens, and again he survives while someone else gets killed. Meanwhile, in both episodes so far, mention is made of a mysterious, secret crime syndicate called the ACS, the ‘Asia Confidential Service’.

From wikipedia.org / © Ken Domon

Things become yet more outlandish. Hanio is hired next by a schoolboy who wants him to look after his mother: “She’s ill, but she’ll recover right away with care from you.” What makes this life-threatening is the fact that the boy’s mother is a vampire. Hanio soon finds himself living with the pair, having his blood gradually and gently siphoned away by the vampirical mum, but he’s languidly happy as his death seems to draw near: “he truly enjoyed lounging around at home, basking in the family atmosphere.” This is the most baroque part of the book, but it actually works well. (Thinking about it, I’m not surprised that Mishima and vampires – at least, those of the brooding, aristocratic sort – are a good match.)

The next episode – following another death, again not Hanio’s – is less effective. He becomes embroiled in an espionage saga involving two foreign powers, ‘Country A’ and ‘Country B’, a stolen necklace, an all-important cipher key, and several dead secret agents. It all feels a bit tired, despite Mishima throwing into the plot some mysterious carrots as a whacky extra ingredient. The ‘Country A’ and ‘Country B’ stuff reminds me of old 1960s TV shows like Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1964-68), where the villains were often foreigners, but ones acting on behalf of ‘unnamed hostile powers’, to avoid the show offending anybody.

After that, Hanio ends up living in a new, lavish apartment – his ‘Life for Sale’ business has earned him a fair amount of yen by this point – which he rents off a rich, drug-addled hippy-chick called Reiko. (Reiko’s dotty old mum explains to him that her daughter takes “that drug beginning with L…”) This enables Mishima, through the character of Hanio, to express his opinion of hippies, which as you might expect is not high. “They were seekers after ‘meaninglessness’, all right, but he could not imagine them having the guts to confront the real thing when it inevitably came calling.” Hanio gets romantically involved with the unhinged Reiko who, for all her wild talk, has a worryingly conventional vision of what married life with him will be like: “Daddy comes home every day at six-fifteen, so I have to start cooking. When everything’s bubbling away nicely, I’ll hurry up and put on my make-up in time for when Daddy turns up…”

Hanio eventually flees from Reiko. In the book’s closing pages, becoming increasingly paranoid, he believes that it’s not just her who’s pursuing him. He might also have the ACS – the Asia Confidential Service mentioned by characters in the novel’s earlier sections – chasing him too.

Thus, Life for Sale is a mish-mash of crime, spy, horror, romance and comedy themes, leavened with a little of Mishima’s characteristic angst. If not every episode is successful, that’s not a great problem – a few pages later, another episode arrives, which the reader may enjoy better. Meanwhile, it suggests the books by Mishima that have long been available in translated form may have given English-language readers a blinkered view of him, i.e., that he was a humourless, cerebral misery-guts who specialised in Literature with a capital ‘L’. But Life for Sale, whose English-language translation didn’t appear until 2019, gives a rather different impression, that he was less of a literary snob, enjoyed genre fiction and had a playful side.

And I hear that last year saw the first English translation of another Mishima novel, a 1962 one called Beautiful Star. Its translator was Stephen Dodd, who also rendered Life for Sale into English. Beautiful Star sees Mishima having a go at science fiction. It’s about “a Japanese family who wake up one day convinced that they are each aliens from a different planet inhabiting human bodies.”

Mishima and aliens? I can’t wait to read that one.

© Penguin Books