From the Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Today, November 30th, is Saint Andrew’s Day, the national day of Scotland. To mark it, I’d like to post something about a favourite topic of mine, the Scots language. And yes, the way that non-Gaelic and non-posh Scots have spoken for centuries has been classified as a language, a separate one from ‘standard’ English, by organisations like the EU and linguistic resources like Ethnologue.

Sadly, I think that Scots is now living on borrowed time. It’s not likely to expire due to the disapproval of educators who dismiss it as a debased dialect (or accent) of standard English and regard it as the ‘wrong’ way to speak, although their hostility certainly didn’t help its status in the past. No, the fatal damage to Scots has probably been inflicted by television, exposing Scottish kids to a non-stop diet of southern-England programming and conditioning them to speak in Eastenders-style Mockney or, worse, in bland, soulless ‘Estuary English’.

Personally, I love listening to and reading Scots. Here are my favourite Scots words starting with the letters ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ that I’d be sad to see slip into linguistic extinction. Most of the definitions given come from my heavily used copy of the Collins Pocket Scots Dictionary.

Agley (adv) – wrong, askew. The saying, ‘The best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry’ (which provided John Steinbeck with the title of his second-most famous novel) is an anglicised version of lines from the poem To a Mouse by Scotland’s greatest bard Robert Burns: “The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men / Gang aft agley.”

Aiblins (adv) – perhaps. The late, great Glaswegian writer Alasdair Gray borrowed this word for the surname of the title character in his short story Aiblins, which appeared in the collection The Ends of Our Tethers (2003). This is about a creative writing professor being tormented by an eccentric student called Aiblins who is, perhaps, a literary genius or is, perhaps, just a fraud.

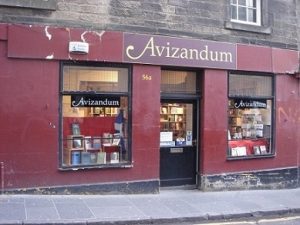

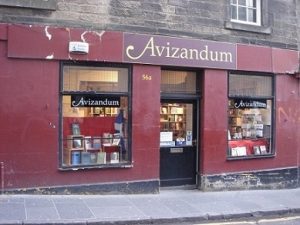

Avizandum (noun) – a word in Scots law meaning, to quote the Collins Pocket Scots Dictionary, ‘a judge’s or court’s consideration of a case before giving judgement’. Avizandum is also the name of a bookshop on Edinburgh’s Candlemaker Row specialising in texts for Scottish lawyers and law students. Not being a lawyer, I’ve never had cause to go into Avizandum-the-shop, but I do think it’s the most majestically titled bookstore in Scotland.

Bairn (n) – a baby or young child. I once saw an episode of Star Trek (the original series) in which Scotty lamented, after Mr Spock had burned out his engines in some ill-advised space manoeuvre, “Och, ma poor wee bairns!” So I guess this Scots word is safe until the 23rd century at least. Also, the Bairns is the nickname of Falkirk Football Club, so it shouldn’t be dying out in Falkirk anytime soon, either.

Bahookie (n) – rump, bum, backside, ass or, to use its widely-deployed-in-Scotland variant, arse.

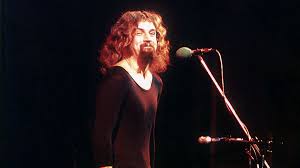

Bampot (n) – a foolish, stupid or crazy person. During the documentary Big Banana Feet (1976), about Billy Connolly doing a stand-up tour of Ireland, Connolly responds to a heckler with the gruff and memorable putdown, “F**king bampot!”

Bawbag (n) – literally a scrotum, but normally, to quote the online Urban Dictionary site, ‘a derogatory name given to one who is annoying, useless or just plain stupid.’ Thus, when former United Kingdom Independence Party leader Nigel Farage steamed into Edinburgh in May 2013 in a bid to raise UKIP’s profile north of the border, he ended up besieged inside the Canon’s Gait pub on the Royal Mile by a horde of anti-racism protestors who chanted, “Nigel, ye’re a bawbag / Nigel, ye’re a bawbag / Na, na, na, hey!”

Bertie Auld (adj), as in “It’s Bertie Auld tonight!” – rhyming slang for cauld, the Scottish pronunciation of ‘cold’. Bertie Auld was a Scottish footballer who played for Celtic, Hibernian, Dumbarton and Birmingham City and whose finest hour was surely his membership of the Lisbon Lions, the Celtic team that won the European Cup in 1967.

Bide (v) – to live. Derived from this verb is the compound noun bidie-hame, which refers to a partner whom the speaker is living with but isn’t actually married to.

Blether (v) – to talk or chatter. Journalist, editor and Rupert Murdoch’s one-time right-hand-man Andrew Neil used this word a lot while he was editor-in-chief at Scotsman publications. He was forever fulminating against Scotland’s blethering classes – the equivalent of the ‘chattering classes’ in England who were so despised at the time by the English right-wing press, i.e. left-leaning middle-class people who spent their time holding dinner parties, drinking Chardonnay and indulging in airy-fairy political discussion about how Britain should have a written constitution, proportional representation, devolution, etc. Then, however, Neil started working for the BBC in London and suddenly all his references to blethering ceased.

Boak (v / n) – to vomit / vomit, or something unpleasant enough to make you want to vomit. One of those Scots words that convey their meaning with a near-onomatopoeic brilliance. In his stream-of-consciousness novel 1982 Janine, Alasdair Gray – him again – represents the main character throwing up simply by printing the word BOAK across the page in huge letters.

From pinterest.co.uk

Bowffin’ (adj) – smelling strongly and unpleasantly. Once upon a time, mingin’ was the favoured Scots adjective for ‘smelly’. Now, however, mingin’ seems to have packed its bags, left home and become a standard UK-wide slang word – with a slight change of meaning, so that it denotes ugliness instead. It has thus fallen upon the alternative Scots adjective bowffin’ to describe the olfactory impact of such things as manure, sewage, rotten eggs, mouldy cheese, used socks, on-heat billy goats, old hippies, etc.

Breenge (v) – to go, rush, dash.

Bourach (n) – sometimes a mound or hillock, but more commonly a mess or muddle. Charmingly, this has recently evolved into the term clusterbourach (inspired by the less ceremonious ‘clusterf*ck’), which Scottish politicians have used to describe the absolute hash that the London government is making of the Brexit process.

Callant (n) – a lad or young man. The Common Riding festival held annually in the Borders town of Jedburgh is called the Callant’s Festival. Accordingly, the festival’s principal man is called the Callant.

Carlin (n) – an old woman, hag or witch. Throughout Scotland there are stone circles, standing stones and odd rock formations that are known as carlin stones, presumably because people once linked them to the supernatural and imagined that witches would perform unsavoury rituals at them.

Carnaptious (adj) – grumpy, bad-tempered or irritable. For example, “Thon Belfast singer-songwriter Van Morrison is a right carnaptious auld c**t.” There’s a lot of carnaptiousness in Scotland and another common adjective for it is crabbit.

Chib (n/v) – a knife, or to stab someone. Considering the popularity in modern times of wearing Highland dress at Scottish weddings, and considering the custom of having a ceremonial sgian-dhu (i.e. dagger) tucked down the side of the hose (i.e. socks) in said Highland dress, and considering the amount of alcohol consumed at such affairs, it’s amazing that Scottish weddings don’t see more chibbing than they do.

Chitter (v) – nothing to do with the sound that birds make, this means to shiver.

Clarty (adj) – dirty. A dirty person, meanwhile, is often called a clart. And a pre-pubescent boy who avoids soap, shampoo, showers and clean socks and underwear, like Pig Pen used to do in the Charlie Brown comic strips, would undoubtedly be described in Scotland as a wee clart.

Cleek (v) – to hook, catch or capture. It’s also a noun denoting a large type of hook, especially the gaffe used by fishermen, and poachers, when landing fish. At least once, in my hometown next to the salmon-populated River Tweed, a cleek has also been used as an offensive weapon.

From en.wikipedia.org

Cloots (n) – a plural noun meaning hooves. By extension, Cloots came to be a nickname for the world’s most famous possessor of a pair of hooves, Auld Nick, a.k.a. the Devil. In his poem Address to the Deil, Robert Burns not only mocks Auld Nick but brags that, despite his wild and wanton behaviour in this present life, he’ll escape the fiend’s clutches and avoid going to hell: “An’ now, auld Cloots, I ken ye’re thinkin’ / A certain bardie’s rantin’, drinkin’ / Some luckless hour will send him linkin’ / To your black pit / But faith! he’ll turn a corner jinkin’ / An’ cheat ye yet.”

Clype (n) – a contemptible sub-species of schoolchild, i.e. the type who’s always running to the teachers and telling tales on his or her schoolmates.

Colliebuckie (n) – a piggy-back. Scottish playgrounds once echoed with cries of “Gie’s a colliebuckie!”

Corbie (n) – a crow or raven. The knowledgeable Australian musician / singer / writer Nick Cave uses this word at the beginning of his gothic novel And the Ass Saw the Angel, which has a couple of ‘sly corbies’ circling in the sky above the dying hero.

Cowpt (adj) – overturned, fallen-over. Often used to describe sheep when they fall onto their backs, can’t get up again and run the risk of breaking their spines. Around where I live, there’s a story of a young farmer who was about to get married and, just before his stag party in Edinburgh, was collected at his farmhouse by a coachload of his mates. As the coach was driving away from the farm, someone on board spotted a cowpt ewe in one of the fields. Jocularly, the young farmer told the coach-driver to manoeuvre the vehicle off the road, into the field and across to the spot where the unfortunate beast was on its back, which he did. The young farmer got out and put the cowpt ewe on its feet again; but meanwhile all the other sheep in the field, seeing the coach and not knowing the difference between it and a tractor carrying a load of hay, flocked around it expecting to be fed. That left the stag-party and their transport marooned amidst a sea of woolly white fleeces.

I’ll return to this topic in this blog and cover further letters of the alphabet.

© Viz Unicorn Entertainment / Brent Walker