© Universal Pictures / Polygram Pictures

When I think about the films that I saw and loved during the formative years of my mid-to-late-teens, films like Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982), George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1979), Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), George Miller’s Mad Max II (1981), Terry Gilliam’s The Time Bandits (1981), Jean-Jacques Beineix’s Diva (1981), John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) and Walter Hill’s 48 Hrs (1982), I instinctively assume they were released, oh, maybe a quarter of century ago. It scares me when I actually do the maths and realise that no, 40 years have now passed, or will have passed soon, since their original release. Yes, I know the platitudes – ‘Time waits for no man’, ‘None of us are getting younger’ and so on. Still, it comes as a mighty shock to realise these films are now as far back in time from 2021 as Stagecoach (1939) with John Wayne, or The Wizard of Oz (1939) with Judy Garland, were back in time from when they first hit the cinemas in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Anyway, August 2021 has served up yet another cinematic reminder of what a dribbling old fart I now am. I’ve discovered that exactly 40 years have elapsed since the release of John Landis’s much-loved horror comedy, An American Werewolf in London (1981).

The film won the first-ever Oscar awarded for Best Make-Up, courtesy of legendary make-up artist Rick Baker. Though what Baker pulls off when he transforms star David Naughton into the titular werewolf, elongating his face into a muzzle and his hands into paws, making fangs sprout from his jaws and claws from his fingertips, having long black fur ooze through his skin, is more a triumph of practical special effects. Ironically, while American Werewolf deserves to be seen on a cinema-sized screen for those effects to be appreciated in their full glory, I’ve only ever seen it on a small screen. My first viewing came in 1982, at a private hostel called Balmer’s in the Swiss town of Interlaken, where the management would entertain its guests in the evening by showing them recent movies using a TV set and video-cassette recorder. The evening I stayed there, they showed American Werewolf on video and I watched it amid a bunch of American backpackers not dissimilar to the pair of American backpackers, David (Naughton) and Jack (Griffin Dunne), whom we’re introduced to and then see savaged by a werewolf during the film’s opening minutes.

Since then, I’ve seen it umpteen times, through late-night TV showings, or on video (invariably at a mate’s house and accompanied by a carryout of beer), or more lately on my laptop, and it’s never failed to work its magic on me.

When I first watched it, I thought it a rather strange film. Movies that combined horror and comedy weren’t anything new, and the previous decade had seen both Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein (1974) and Stan Dragoti’s Dracula spoof Love at First Bite (1979). However, those and pretty much all ‘horror-comedies’ until then had emphasized the comedy and used the horror merely as a seam from which un-bloody, family-friendly jokes were mined. Little or nothing was shown that was actually horrifying.

American Werewolf, on the other hand, quite happily treats its audience to images of flesh being ripped, throats being slashed, heads being bitten off and so on. Indeed, much of the humour is generated by the visceral horror, especially in the scenes where Jack, killed in the opening minutes, returns as an affable, chatty zombie to warn David that, having been bitten by a werewolf, he’s going to turn into one himself come the next full moon. With each appearance, Jack is considerably more decayed. At one point his alarming appearance prompts David to exclaim, “I will not be threatened by a walking meat loaf!”

© Universal Pictures / Polygram Pictures

Also strange is the film’s unconventionally leisurely pacing up until its main event, David turning into a werewolf and going on a rampage, which takes place at the hour-mark. Not that anything before that key moment is boring. The film is an endearing hodgepodge of sub-plots, themes and observations that happen to take director / writer John Landis’s fancy. These include David’s romance with Alex Price (the radiant Jenny Agutter), a nurse working in the London hospital where he ends up following the initial werewolf attack. This has been hushed up and passed off as an attack by an ‘escaped lunatic’, a term that shows the film’s age a wee bit. I don’t think you can talk about ‘lunatics’, even in a horror film, in the politically correct 2020s. Come to think of it, when David and Alex finally get it on, it’s to the strains of Van Morrison’s Moondance, which shows the film’s age too. It’s been a long time indeed since the curmudgeonly Van Morrison could be associated with anything horny.

Landis also shows us David suffering from bizarre dreams, presumably the result of the lycanthropic gene that’s now in his body. These include one memorable sequence where he dreams of his family being slaughtered by decayed-faced werewolves in Nazi uniforms while they watch The Muppet Show. And Landis makes some bemused observations too about British life in the early 1980s – the less-than-rosy reception that David and Jack get when they blunder into a Yorkshire pub (the Slaughtered Lamb) at the beginning; the London Underground being full of surly punk rockers; British TV consisting of three terrestrial channels that show only darts, News of the World adverts and the BBC Test Card; British kids being weird little brats who shout “No!” all the time or laugh manically when their dogs bark at you; grumblings about inflation; grumblings about British food; and the rain. The rain depicted in American Werewolf isn’t typical horror-movie, thunder-and-lightning rain. It’s just grey, depressing British rain that always seems to fall at the wrong moment.

This social commentary continues after David transforms from man to werewolf on the next full moon and paints London red. His victims represent both ends of the spectrum of the nascent Margaret Thatcher’s Britain. They include homeless down-and-outs huddling around a fire down by the edge of the Thames and an annoyingly cheerful proto-yuppie couple, who continue to be annoyingly cheerful even after they’ve been torn apart and, like Jack, come back to haunt David as the living dead. Landis also has a dig at the then-sleaziness of central London by having the film’s climax (ouch!) begin in a porno cinema in Piccadilly Circus, where the punters are watching a spectacularly gormless British sex movie called See You Next Wednesday. A fictitious ‘film within a film’, See You Next Wednesday is foreshadowed earlier on. When David claims a victim in the Tottenham Court Road tube station, we see a poster advertising it on one of the walls.

© Universal Pictures / Polygram Pictures

One thing about American Werewolf that doesn’t get enough praise is its supporting cast. David Naughton, Jenny Agutter and Griffin Dunne have all won plaudits and yes, they’re great, but there’s plenty of solid acting talent backing them up. John Woodvine gives a commanding and unflappable performance as Dr Hirsch, the medical man who resolves to find out what’s really going on after the injured, seemingly-raving David arrives in his care in London. Up north, meanwhile, the role of main villager at the Slaughtered Lamb pub required a bald-headed, rough-looking Yorkshireman and only one man could handle the job, the splendid Brian Glover. Although Glover is fondly remembered for his comic turn as the pompous PE teacher Mr Sugden in Ken Loach’s Kes (1969), the scene in American Werewolf where he entertains the Lamb’s patrons with his ‘Remember the Alamo!’ joke is surely as funny. Those patrons include a young and shifty-looking Rik Mayall. I assume Mayall and Glover hit it off because, years later, I recall Glover making a guest appearance in Mayall’s TV show Bottom (1991-95).

Frank Oz appears briefly as a snotty American Embassy official – Oz recently noted, “Whenever John (Landis) needed a prick in a film, he called me” – and Cockney actor Alan Ford pops up as a talkative London cabbie who enlightens David about the carnage he caused (but didn’t remember causing) the night before: “Six of ’em… all in different parts of the city, all mutilated… He must be a real, right maniac, this fellah!” In micro-cameos, you might just spot Landis himself as the poor schmuck who, during the final werewolf-induced carnage in Piccadilly Circus, gets struck by an out-of-control car and is knocked through a shop window, and legendary James Bond stuntman Vic Armstrong as the driver of the double-decker bus that also comes to grief.

© Universal Pictures / Polygram Pictures

If the film has a fault, it’s that it ends so abruptly. I guess Landis was trying to be shockingly and modishly nihilistic in depicting David’s final fate, but it feels like a cheat that there’s so little build-up, tension and drama in those last minutes. That said, Jenny Agutter as the now-distraught Alex still gives the truncated finale an emotional punch.

Even the last couple of minutes of American Werewolf, disappointing though they are, are a hundred times better than the entirety of the belated sequel An American Werewolf in Paris (1997), made by a different team from the one that made the original. It’s a dire, slipshod, intentionally dumb-assed film that shits werewolf-dung all over the memory of its predecessor, not least because it dispenses with Rick Baker’s practical effects and renders its werewolves in lousy-looking, cartoonish CGI.

More recently, there’s been talk of a remake. But a new American Werewolf in London couldn’t hope to capture the essence of the time – as opposed to the place – that made the original so special. The 1981 film is unique because it showed the personality of London, and Britain, that existed 40 years ago, albeit through the eyes of a bemused main character and bemused writer / director who were both outsiders.

I doubt very much if a tale of an American werewolf prowling around 2021 London would win the affection of audiences. We’re talking a charmless modern London of oligarchs, dirty money, hollowed-out neighbourhoods, rapacious developers, Mayor Johnson’s ego-trip skyscraper developments, embarrassing white elephants like the Millennium Dome, Emirates Air Line and Marble Arch Mound, and exorbitant housing and living costs – there’s no way Nurse Alex could afford a flat of her own, for David to shelter in, as she did in 1981. Mind you, I might warm to a remake if it had the werewolf chomping on Nigel Farage’s head.

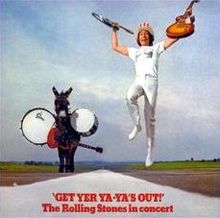

Here’s a lovely re-invention of the movie poster for An American Werewolf in London by the artist and illustrator Graham Humphreys. I hope he doesn’t mind me using it here.