From wikipedia.com / © Vertigo Records

I’m no fan of lengthy international sporting competitions – apart from the Rugby and Football World Cups – and I reacted with a weary shrug to the recent holding of the Commonwealth Games in the English Midlands city of Birmingham. However, I’d have willingly sat through the Games’ twelve days of sporting endeavour, bored out of my wits, just to be present at the occasion’s closing ceremony. For this offered a few minutes that, in my mind, were the musical highlight of August 2022, if not the year 2022. I’m talking about the sight of former Black Sabbath singer and famous Birmingham son Ozzy Osbourne coming up through a stage-trapdoor into a shroud of blood-red mist to sing the 1970 Sabbath classic Paranoid, with Ozzy’s old Sabbath comrade Tony Iommi thumping away on electric guitar.

Apparently, Ozzy had originally turned down an invitation to sing at the ceremony due to health issues. Quite a lot of health issues, in fact – Parkinson’s disease, neck and spine surgery, depression, blood clots, nerve pain. But at the last minute, deciding the show must go on, he jumped on a flight from Los Angeles and made a surprise appearance in his old home city. And though I was no fan of the sporting stuff, I was delighted to see him perform at this, the biggest event in Birmingham for years. Long before anyone had heard of Peaky Blinders (2013-22), Ozzy – catchphrase: “Oi’m the Prince o’ Dawkness!” – had made it cool to be a Brum.

Anyway, this has inspired me to dust down and repost the following item. It was written in 2017, just after those mighty metallers Black Sabbath had played their last-ever gig.

The third commandment tells us to keep the Sabbath holy. Well, I believe in honouring the Sabbath but I’m not talking about the seventh day of the week. I’m talking about Black Sabbath, the 49-year-old heavy metal band who played their last-ever gig two nights ago.

Fittingly, Black Sabbath’s farewell performance took place at the Genting Arena in Birmingham, the city where it all started for them. Guitarist Tony Iommi, bassist Geezer Butler, drummer Bill Ward and incomparable – many would say incorrigible – singer Ozzy Osbourne grew up in Aston, one of Birmingham’s working-class suburbs. Prior to forming the band, they did a variety of unglamorous jobs there, including delivering coal, labouring on building sites and working in a sheet metal factory, car plant and abattoir. Iommi ended his time in the steelworks with an accident that sheared off two of his fingertips and nearly ruined his budding career as a guitarist. Osbourne, meanwhile, took up housebreaking and got jailed for six weeks.

Butler told the BBC recently, “It wasn’t a great place to be at that time. We were listening to songs about San Francisco. The hippies were all peace and love and everything. There we were in Aston. Ozzy was in prison from burgling houses, me and Tony were always in fights with somebody… we had quite a rough upbringing. Our music reflected the way we felt.”

© Vertigo Records

If they felt miserable in Aston and channelled that misery into their music, I can only say the misery was worth it. The first, eponymously-named song on their first, eponymously-named album in 1970 sets the tone for Black Sabbath’s career of evil. It’s a gloriously dark and doom-laden affair, opening with rumbles of thunder, the sluicing of heavy rain and the clanging of altar bells. These give way to a funereal chug of heavy guitars and the eerie high-pitched squalls of Ozzy’s voice (“What is this that stands before me? / Figure in black which points at me-e-ee?”), which later speed up for a tumultuous but still ominous climax. I imagine that if any of those peace-and-love hippies whom Butler referred to had gone to a Sabbath gig in 1970 (having ingested some psychedelic substances beforehand) and the gig had opened with this number, they’d have probably fled from the venue screaming in terror with their hands clamped over their ears.

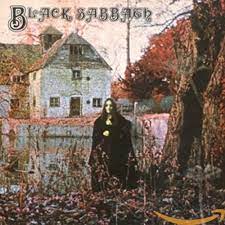

Iommi and Butler were horror-movie fans and their music had a horror-movie vibe. Even the band’s name came from a scary film, 1963’s Black Sabbath, directed by the legendary Mario Bava and starring the legendary Boris Karloff. Also horror-movie-esque is the cover of the first Sabbath album, showing a black-robed lady looming spectrally in the middle of a spooky autumnal landscape – the building in the background is actually Mapledurham Watermill in Oxfordshire. I find it cool that nobody knows the identity of the woman, presumably a briefly-hired model or actress, who posed for the picture. Iommi has claimed that, later, she turned up at one Sabbath concert and said hello to the band. But I like to think she’d never been at the original photo-shoot at all. Rather, she was a ghost that haunted the watermill – and when they developed the cover-photo, her wraithlike image had somehow imposed itself on it.

© Vertigo Records

Black Sabbath produced another album in 1970, Paranoid, which was choc-a-bloc with groovily heavy tunes – the famous title track, the skull-crushing Iron Man, the nihilistic War Pigs and the sublimely dreamy and trippy Planet Caravan, which has been described as ‘the ultimate coming-down song’. The following year’s Master of Reality gave us the jaunty but provocative After Forever (“Would you like to see the Pope on the end of a rope / Do you think he’s a fool?”) and the apocalyptic Children of the Grave. Other classic songs included Supernaut, which turned up on the 1972 album Vol. 4; the exhilarating title track of 1973’s Sabbath Bloody Sabbath that’s perhaps my favourite Sabbath song ever; and the similarly exhilarating Symptom of the Universe on 1974’s Sabotage, which suggests (to me, anyway) Sabbath were secret forbearers of punk rock. 1976’s Technical Ecstasy and 1978’s Never Say Die are less acclaimed and lack a truly killer track, but I’m still partial to them both.

In 1980 we got Heaven and Hell which – shock! horror! – didn’t have Ozzy Osbourne doing vocals. The singer had been sacked from the band due to his massive substance abuse and consequent massive unreliability. While Ozzy maintains that he was no worse a wreck than the other three band-members were at the time, it was surely tough working with a man prone to such misfortunes as snorting a line of ants he’d mistaken for a line of cocaine or being caught by the San Antonio police urinating over the Alamo whilst dressed in a frock. Making a Black Sabbath album without Ozzy sounds as feasible as filming The Lord of the Rings without Gandalf, but Iommi, Butler and Ward wisely recruited the late, great Ronnie James Dio as a replacement. Dio gave Black Sabbath a new lease of life. He made them sound different – his operatic voice a contrast to the wailing alienness of Ozzy’s – but I have no complaints about the resulting album, full of spiffing tracks like Children of the Sea, Neon Knights and Die Young.

© Vertigo Records

Dio sang on the next album for Black Sabbath, 1981’s Mob Rules, and returned to sing on 1992’s Dehumanizer; but they were the only Sabbath albums for a long time that were any good. During the 1980s and 1990s Iommi was the sole founding member who stuck with the band and a succession of jobbing musicians contributed to the records. Singers included Ian Gillan and Glenn Hughes, two alumni of Sabbath’s more mainstream 1970s rivals Deep Purple. Meanwhile, the band seemed to get through drummers at a rate worthy of Spinal Tap, with the ELO’s Bev Bevan, the Clash’s Terry Chimes and the ubiquitous Cozy Powell banging the skins at various times. To be honest, the band’s output during this period – 1983’s Born Again, 1986’s Seventh Star, 1987’s The Eternal Idol, 1989’s Headless Cross, 1990’s Tyr, 1994’s Cross Purposes, 1995’s Forbidden – is pretty rubbish.

Happily, the original line-up had reconciled by the late 1990s and they’ve played together sporadically since then, at least when other work commitments (like Ozzy’s solo career), illness (Iommi was diagnosed as having lymphoma in 2012) and plain old quarrelling (Bill Ward fell out with everyone else and quit in 2012) didn’t get in the way. In 2013 they even managed to produce a new album, 13, which while not quite up to their old standards got some positive reviews and produced a decent single, God is Dead? Filling in for Ward on the drums was Brad Wilk from Rage Against the Machine. I imagine for Wilk getting this job must have been a dream come true.

Well, it seems they’ve finally called it a day. Maybe that’s just as well in Ozzy’s case, since the old boy’s 67 now and surely needs to take it easy after a lifetime of drugs, alcohol, excess and idiocy. (At Christmas, after the news that George Michael and Status Quo’s Rick Parfitt had died within the space of 24 hours, a friend said to me worriedly, “At this rate Ozzy’s not going to make it to the Bells.”)

They deserve to enjoy their retirement for their legacy is huge. Their weighty fingerprints are all over musical movements like grunge and hardcore punk. And they’re clearly major influences on such metallic sub-genres as black metal, doom metal, goth metal, power metal, sludge metal, speed metal and stoner metal. Indeed, they’re responsible for more metal than the Brummie steelworks where the young Tony Iommi lost his fingertips and almost lost his future in music.

From youtube.com / © BBC